Maria A. Nagel

John R. Corboy

In humans, morbidity and mortality caused by cancer, infection, and possibly autoimmunity increase with age. Viral infections of the nervous system contribute to this morbidity and mortality in both the community and in long-term care facilities. In 2004, persons 65 years and older comprised 36.3 million, or 12.4%, of the U.S. population. With the U.S. population 65 years and older continuing to rise to a projected 40 million in 2010 and 71.5 million in 2030 (www.aoa.gov/PROF/Statistics/profile/2005/4.asp), it is important to recognize the clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, complications, and sequelae of viral infections of the nervous system in this vulnerable patient population.

Viral diseases have several unique features in the elderly. First, infections can be more frequent and severe in this population. For West Nile virus infection, older age seems to be a main risk factor for severe meningoencephalitis and death; individuals older than 50 years have a 10-fold higher risk of developing neurologic symptoms, and the risk is 43 times higher in individuals older than 80 years (53). Second, different viral illnesses are more common in older individuals than in younger individuals, such as reactivation of varicella-zoster virus (VZV) to cause herpes zoster (shingles). Third, clinical presentation can differ, with the elderly patient presenting with atypical or fewer symptoms. Fourth, diagnostic procedures may have different yields, such as difficulty with lumbar puncture with degenerative spine disease. Fifth, treatment needs to take into account the higher incidence of adverse drug effects in this population and other comorbidities, such as renal failure. And finally, long-term sequelae of viral illnesses need to be recognized, such as the occurrence of post-polio syndrome (PPS) years after recovery from an initial acute attack of the poliomyelitis virus.

The increased susceptibility to infection in the elderly population is most likely multifactorial. Dysregulation of the immune system with ageing, or immunosenescence, is believed to be an important contributor to morbidity and mortality in the elderly. The mechanisms that underlie these age-related defects are broad and range from defects in the hematopoietic bone marrow to defects in peripheral lymphocyte migration, maturation, and function (28). However, dysregulated T-cell function is believed to play a critical role because these cells are vital in mediating both cellular and humoral immunity. A number of factors have been associated with the decline of T-cell function with age including hematopoietic stem-cell defects; however, chronic involution of the thymus gland with resultant decreased output of naïve T cells is believed to be one of the major contributing factors to loss of immune function with age (29). Aside from immunosenescence, epidemiologic factors, such as exposures to infection in long-term health care facilities; malnutrition, which may result in decreased immune function (12); and comorbid conditions, such as diabetes and stroke, may also contribute to increased susceptibility to infections in the elderly.

Following is a discussion of the most common viral illnesses affecting the nervous system in the elderly including herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) caused by VZV and PPS seen years after poliomyelitis virus infection.

VARICELLA-ZOSTER VIRUS AND NEUROLOGIC DISEASE

VZV is an exclusively human, double-stranded DNA alphaherpesvirus. Primary infection causes chickenpox (varicella), after which the virus becomes latent in cranial nerve ganglia, dorsal root ganglia, and autonomic ganglia along the entire neuraxis. Virus reactivation typically occurs in elderly, associated with an age-related decline in cell-mediated immunity, and in immunocompromised individuals. Multiple neurologic complications are seen with VZV reactivation. The most common are herpes zoster (shingles), which is characterized by pain and rash in one to three dermatomes, and PHN, which is pain that persists for >3 months and sometimes years after resolution of rash. Less frequently, VZV reactivation can cause vasculopathy, myelitis, progressive outer retinal necrosis, and zoster sine herpete (dermatomal pain without rash) (25).

HERPES ZOSTER

Herpes zoster affects some 600,000 to 900,000 mostly elderly or immunocompromised people in the United States each year (16,64). Its annual incidence is

approximately 5 to 6.5 per 1,000 at age 60, increasing to 8 to 11 per 1,000 at age 70 (16).

approximately 5 to 6.5 per 1,000 at age 60, increasing to 8 to 11 per 1,000 at age 70 (16).

Herpes zoster usually begins with a prodromal phase characterized by pain, itching, paresthesias (numbness/tingling), dysesthesias (unpleasant sensations), and/or sensitivity to touch (allodynia) in one to three dermatomes. A few days later, a unilateral maculopapular rash appears on the affected area, which then evolves into vesicles. These vesicles usually scab over in 10 days, after which the lesions are not contagious. Multiple dermatomes or a generalized infection are more likely to be involved in immunosuppressed patients, such as patients with a hematologic malignancy or iatrogenic immunosuppression. Rarely, the prodrome is not followed by typical zoster lesions (zoster sine herpete), making diagnosis difficult. In most patients, the disappearance of the skin lesions are accompanied by decreased pain, with complete resolution of pain within 4 to 6 weeks.

Herpes zoster can affect any level of the neuraxis, including cranial nerves, but is most frequently seen in thoracic dermatomes followed by lesions on the face, typically in the ophthalmic distribution of the trigeminal nerve [herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO)]. HZO is often accompanied by zoster keratitis, resulting in blindness if unrecognized and not treated. Thus, if visual symptoms are present in patients with ophthalmic distribution zoster, a slit-lamp examination by an ophthalmologist is imperative, especially if skin lesions extend to the medial side of the nose (Hutchinson sign). Herpes zoster can also affect the cranial nerve VII (geniculate) ganglion, causing weakness or paralysis of ipsilateral facial muscles with skin lesions in the external auditory canal/tympanic membrane (zoster oticus) and/or anterior two thirds of the tongue or hard palate. This peripheral facial weakness and zoster oticus constitutes the Ramsay Hunt syndrome [reviewed by Sweeney and Gilden (57)]. Additional cranial nerves may be involved, leading to tinnitus, hearing loss, nausea, vomiting, vertigo, and nystagmus. Less common presentations of herpes zoster include optic neuritis/neuropathy from optic nerve involvement (10,38); ophthalmoplegia from cranial nerves III, VI, and IV involvement (5,10,34,55); and osteonecrosis and spontaneous tooth exfoliation from involvement of the maxillary and mandibular distribution of the trigeminal nerve (22,37,63). Lower motor neuron-type weakness in the arm or leg may also follow cervical or lumbar distribution zoster, respectively [reviewed by Merchet and Gruener (40) and Yoleri et al. (68)]. Diaphragmatic weakness following cervical zoster (4) and abdominal muscle weakness, leading to abdominal herniation, following thoracic zoster (59) have also been reported.

Diagnosis of herpes zoster is straightforward based on the clinical presentation, characteristic rash, and pain/altered sensation. However, there are cases in which rash does not follow the prodrome (zoster sine herpete), making the diagnosis more challenging. Patients may only present with dermatomal distribution pain that does not cross the midline or unilateral facial or limb weakness. In these cases, a fourfold rise in serum antibody to VZV or the presence of VZV DNA in auricular skin, blood mononuclear cells, middle ear fluid, or saliva (20) may assist with diagnosis. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) can also be examined for the presence of VZV DNA and anti-VZV immunoglobulin (Ig) G antibody.

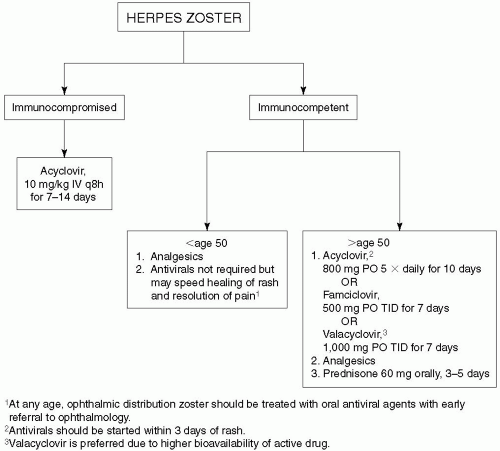

Treatment of herpes zoster is based on the patient’s immune status and age; however, no universally accepted protocol exists. In immunocompetent individuals under age 50 years, analgesics (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, opioids) and topical treatments (calamine lotion, petroleum jelly, local anesthetic creams, occlusive bandages) are used to relieve pain (Fig. 27-1). Oral antivirals (acyclovir 800 mg five times a day for 10 days; famciclovir 500 mg orally three times daily; or valacyclovir 1,000 mg three times daily for 7 days) are not required but will speed the healing of rash and resolution of pain. These antivirals are generally well tolerated. Side effects include nausea, headache, diarrhea, and vomiting. It has also been reported that treatment of herpes zoster with 800 mg/day of oral acyclovir within 72 hours of rash onset may reduce the incidence of residual pain at 6 months by 46% in immunocompetent adults (32). Thus, in immunocompetent individuals over the age of 50, treatment with both analgesics and antivirals are recommended and are essential in patients with ophthalmic distribution zoster. Similarly, treatment of patients with the Ramsay Hunt syndrome within 7 days of onset appears to improve recovery (21,42). In addition to antivirals, prednisone (60 mg orally for 3 to 5 days) has also been used to reduce the inflammatory response, although double-blind, placebo-controlled studies to confirm additional efficacy are lacking. In immunocompromised patients, intravenous acyclovir, 10 mg/kg every 8 hours for 7 to 14 days, is recommended.

POSTHERPETIC NEURALGIA

The most common complication of herpes zoster is PHN, which is characterized by constant, severe, stabbing or burning, dysesthetic pain that persists for >3 months and sometimes years after resolution of the zoster skin lesions. As many as 1 million individuals are affected in the United States (8). The occurrence of PHN is closely associated with age. It is rare in patients younger than 50 years of age but is seen in up to 40% of patients with zoster who are older than 60 years (50). Other risk factors for PHN include severe pain during zoster and a prodrome of severe

dermatomal pain prior to rash. Symptoms tend to improve over time, with less than 5% of patients still having pain at 1 year. However, during this period, pain can be quite debilitating, and the patient’s quality of life can be severely affected, leading to depression. The cause of PHN is unknown, but two non-mutually exclusive theories have been proposed—that the excitability of ganglionic or spinal cord neurons is altered after zoster and that low-grade virus infection persists in ganglia despite resolution of the skin lesions (36,62).

dermatomal pain prior to rash. Symptoms tend to improve over time, with less than 5% of patients still having pain at 1 year. However, during this period, pain can be quite debilitating, and the patient’s quality of life can be severely affected, leading to depression. The cause of PHN is unknown, but two non-mutually exclusive theories have been proposed—that the excitability of ganglionic or spinal cord neurons is altered after zoster and that low-grade virus infection persists in ganglia despite resolution of the skin lesions (36,62).

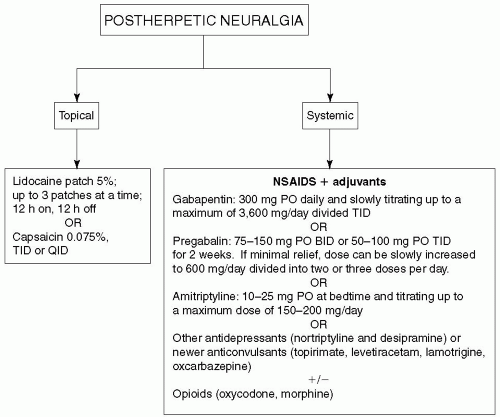

Treatment of PHN is aimed at symptomatic pain relief with use of analgesics, including opiates and neuroleptic drugs, but no universal treatment exists. For topical treatment, lidocaine is administered as 5% patches, with up to three patches applied to the affected area at one time, for up to 12 hours within a 24-hour period (Fig. 27-2). As an alternative, capsaicin 0.075% can also be applied topically three to four times a day, but local skin irritation can limit its use. For systemic treatment of chronic pain, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can be used in conjunction with neuroleptics and other agents if pain is refractory. Gabapentin is widely used, with a starting dose of 300 mg daily and gradually titrating up as needed to a maximum of 3,600 mg/day (divided into three doses daily) (49,51). Pregabalin is given at 75 to 150 mg orally twice daily or 50 to 100 mg orally three times a day (150 to 300 mg/day). If minimal relief is obtained at 300 mg daily for 2 weeks, the dose can be increased to a maximum of 600 mg/day in two or three divided doses. Tricyclic antidepressants, including amitriptyline (10 to 25 mg orally at bedtime with a maximum dose of 150 to 200 mg/day), nortriptyline, and desipramine, lessen the pain of PHN. Newer anticonvulsants, such as topiramate, levetiracetam, lamotrigine, and oxcarbazepine are also being used. Oxycodone (controlled release, 10 to 40 mg orally every 12 hours) or controlled-release morphine sulfate can also be used (17). Levorphanol produces morphinelike analgesia at a dose of 2 mg orally every 6 to 8 hours as needed, with maximum doses of 6 to 12 mg daily (52). Combination treatment with morphine and gabapentin also decreases pain better than either drug alone or placebo (26).

Figure 27-2. Treatment algorithm for postherpetic neuralgia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|