Personal narrative

My journey as an occupational therapist started 20 years ago, 2000 miles away from where I am writing today. Many aspects have changed while other aspects have stayed, surprisingly, the same. In writing this chapter, I hope to share some of the experiences I have had throughout my career and highlight some of the issues that have had an impact on the choices I have made along the way. I shall try to reflect on those aspects that stayed the same, throughout many changes in terms of work context, place and policy. I think these are the powerful messages from occupational therapy philosophy that have become embedded within my personal set of values to shape the meaning of occupation in my own life. I shall introduce some of these influences briefly, as I recall the story of my career, before revisiting them later as I try to explain how they contribute to my current practice.

I studied occupational therapy at the University of the Free State, in Bloemfontein, South Africa, between 1984 and 1988. The work of Vona du Toit, a South African occupational therapist who developed the Model of Creative Ability (Du Toit, 1974), was taught on the course at the time. This model, applicable to all conditions within the spectrum of health care, emphasises the relationship between human volition and action and how this relationship can be used by occupational therapists to understand engagement in activity. Comprehensively written, the model offers information on assessment as well as treatment in occupational therapy, emphasising the centrality of activity as the operational medium for the profession. This model has influenced my work to the extent that it is at times difficult to distinguish which aspects of my practice are not related to it.

Moving on from my student days, my first post as an occupational therapist was in a large general hospital that offered a wide spectrum of possibilities in terms of clinical opportunities. Working with clients who had spinal cord injuries provided a valuable experience of following a small group of patients from the acute stage of disability throughout their rehabilitation. This happened because of my move from the spinal cord unit within the hospital to community services at more or less the same time that the patients made the same move. It was through this holistic experience that I recognised my interest in mental health as I was consistently drawn to and intrigued by the social, emotional and psychological issues confronting this group of young, African men whom I came to know so well. As their community occupational therapist, I was involved in working with the group to match their skills with local needs so as to find sustainable vocational opportunities. Within the political and economic climate at the time, jobs had to be created, rather than applied for, as unemployment figures were high, even amongst those without disability. The group and I were successful in securing a contract with the local casino to produce rattan fruit baskets. I have often used this story to illustrate how any activity can be meaningful within the appropriate context, even though occupational therapists are frequently embarrassed about their basket-weaving heritage.

My next post was in a private, acute psychiatric hospital. I enjoyed developing my skills as a mental health occupational therapist and I conducted a research project exploring the role of the occupational therapist during initial assessment. Job retention and liaison with employers were common features of the post, as the average length of stay in the hospital was 2 weeks. To cope with the fast turnover of clients, I developed a group assessment based on the Model of Creative Ability (Du Toit, 1974).

From here I moved to private practice, first in a multi-disciplinary setting, focusing on mental health in an urban community, with a proportion of work being centred on mental health at work, offering stress management courses to local businesses and schools. Next, we moved as a family to a rural community where I worked as a single practitioner offering a wide range of services including consultation work for a non-government organisation. It was during this time that I decided to study sensory integration theory, as many of the referrals to private occupational therapists in South Africa are children and I thought that it would be wise to satisfy the market need. My experience in mental health, however, drew my attention to the relationship between the sensory processing theories that I was learning and the mental health conditions I had come across before. It was not long before this interest developed and I started researching, informally, how this theory impacts on human behaviour at all stages of development.

I have been working in the field of mental health since moving to England with my family in 1998, and I am currently researching the clinical reasoning of occupational therapists who apply sensory integration theory in their work with adults who have insecure attachment styles. My current post is that of consultant occupational therapist for employment and vocational opportunities across two Mental Health Trusts in the north and east of London and London South Bank University.

In the UK, the role of consultant therapist in the National Health Service was introduced in the NHS Plan (Department of Health, 2000a) and amplified in the strategy for allied health professions (Department of Health, 2000b), which set out to acknowledge and support the development of innovative practice and career development structures. According to this document, the core functions of the consultant therapist are to modernise services, deliver clinical expertise, develop education, training and learning opportunities, support evidence-based practice and research and offer strategic and professional leadership.

Applying these core functions in the field of employment and vocational opportunities allows me to work holistically and integrate the experiences I have had in the past. Before sharing some aspects of my current role, it is, however, necessary to consider the background against which employment and vocational services for persons with mental health problems are being developed.

Vocational rehabilitation

Since 2004, several policy documents published in the UK have cited the relationships between unemployment and health. The direction of these political drivers, are summarised with this quote:

By 2025, disabled people in Britain should have full opportunities and choices to improve their quality of life and will be respected and included as equal members of society. (Prime Minister’s Strategy Unit, 2005)

This vision statement highlighted the current lack of opportunity, choice, quality of life and social inclusion of disabled people and stated an intention to rectify the situation over the next two decades. Employment and vocational opportunities are the key features of social participation and quality of life (ODPM, 2004), and in achieving this vision, access to meaningful employment must be addressed. Figures show that those with mental health problems have the lowest rate of employment among those classified with some form of disability, and that only 21% of persons with long-term mental health problems are in work (ODPM, 2004). Five main reasons for this have been identified by the Social Exclusion Report (ODPM, 2004). These include stigma and discrimination (fewer than 4 in 10 employers would employ someone who declares having a mental health problem); low expectations of health and social care professionals; a lack of clear responsibility for promoting vocational and social outcomes for persons with mental health problems; a lack of ongoing support to facilitate work; and barriers to engage in the community through using transport services, or having access to community centres or housing in areas where these services are provided.

It is alarming for occupational therapists, who consider meaningful participation in occupation as central to their practice (Creek, 2003), to hear that the low expectations of health professionals have been identified as one of the main contributors to the social exclusion of people with mental health problems. The College of Occupational Therapists has, however, taken action to position the profession at the core of implementing changes on a national level, through becoming official partners to the National Social Inclusion Programme (ODPM, 2004). This programme was introduced to drive and coordinate the efforts of all mental health services to actively promote social inclusion.

In north-east London, striving towards more socially inclusive outcomes for people with mental health problems has become a high priority for the two service providers; the North East London Mental Health Trust (NELMHT) and the East London and City Mental Health Trust (ELCMHT). Together these providers offer mental health services to a population close to 1.5 million people. The role of the consultant occupational therapist for employment and vocational opportunities is to ensure that addressing the employment and vocational needs of service users becomes embedded into all aspects of the mental health services provided. Occupational therapy services act as champions for the work.

The role of occupational therapy in the strategy for employment and vocational services in north-east London

The Routes 2 Employment project (R2E) led the way in terms of employment and vocational service provision in NELMHT and ELCMHT. This project has two main aims to address employer practices as well as health care practices. Ultimately, the project hopes to provide more opportunities for people with mental health problems to be included, through employment, as equal members of society.

In terms of employer practices, a toolkit, titled ‘Positive about mental health’ (Colson & Howells, 2005) was produced, which outlines standards of good practice in terms of employing people with mental health problems. Using this toolkit across the two trusts has resulted in better practices regarding their recruitment and retention policies, including a more proactive stance in creating employment opportunities for service users within the service itself.

The project further outlined a strategy to ensure that employment and vocational services are developed within the existing service structures, using occupational therapy as the lead profession. An employment and vocational opportunity (EVO) lead occupational therapist was identified in each of the (seven) London boroughs covered by NELMHT and ELCMHT, creating a virtual team in each of the two trusts. The consultant occupational therapist meets regularly with each team to discuss service development, clinical issues and cascade information to them. They, in turn, take this to their specific areas of work, and the knowledge they have gained is again shared and distributed. This structure tasks occupational therapists with playing an active role in service development, with an expectation that they should be knowledgeable about the local employment market and other employment service providers in the area. They also need to become involved in, or initiate, projects that could create opportunities for those using mental health services. In addition, they need to have the clinical confidence to provide employment and vocational services, and understand what this means within the context of the service setting where they are working.

Occupational therapists as providers of employment and vocational services

According to current evidence, better employment outcomes are achieved for those with severe mental health problems when they are supported in employment situations than when they receive pre-vocational training (Crowther et. al., 2001). The Individual Placement and Support Approach (Bond, 2004), which involves a quick assessment of vocational skills and aspirations, followed by active efforts to find placements in suitable employment settings and then providing ongoing support, is advocated as the way forward for the provision of vocational services in the UK (National Social Inclusion Programme, 2006).

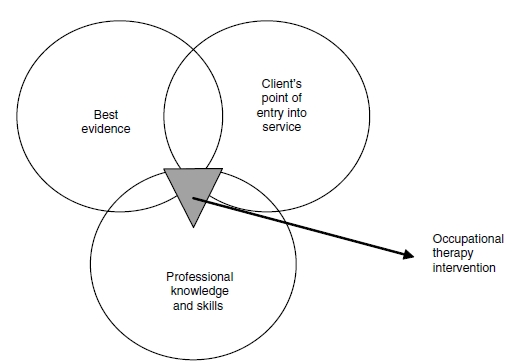

Figure 10.1 Factors influencing occupational therapists’ decision-making in vocational rehabilitation

Several factors impact on occupational therapists’ decision making when they become involved in delivering employment and vocational services. They need to balance the vocational needs of their individual clients at the point of entry into the mental health service with the current evidence and their professional skills as occupational therapists (Figure 10.1).

The individual placement and support approach has been instrumental in making vocational rehabilitation services more relevant to the social inclusion agenda, as it involves active efforts to find suitable placement opportunities in ‘real life’ situations (National Social Inclusion Programme, 2006). To occupational therapists, this approach should not constitute newly acquired knowledge. As early as 1968, Du Toit, a South African occupational therapist and author of the Model of Creative Ability, specified three basic principles of occupational therapy as being (1) that the individual is treated as a totality; (2) that intervention is by means of the patient’s active participation in selected and graded purposeful activity; and (3) that the restoration of the residual work capacity of the individual, or its nearest equivalent, is identified as the fundamental aim of intervention. Nearly 40 years later, occupational therapists have accumulated experiences and knowledge in this field, which they could contribute to the current situation. Descriptions of the individual placement and support approach involve details on service structures, such as integrating vocational programmes into the work of the clinical team or health service or to offer time-unlimited support tailored to individual need (Bond, 2004). What is not described is the content of the support offered, or how to help someone identify vocational goals if this is something they have not considered before. It is in these areas that occupational therapists can offer valuable knowledge. Some of this knowledge is shared in the context of the employment and vocational services offered by occupational therapists in north-east London. They are faced with three key questions when considering their role:

- How are employment/vocational opportunities defined?

- How are vocational issues addressed at different points of entry into the mental health service; for example, how do we approach employment and vocational opportunities on an acute ward, as opposed to in a community mental health team?

- How can the support offered be graded to encourage independence and recovery? These questions will now be considered in turn.

Defining employment/vocational opportunities

The need to define employment and vocational opportunities stems from the need to define the outcomes of occupational therapy in this field. It would be difficult to determine the effectiveness of the service without first agreeing on what is to be achieved. From a political perspective, there is a strong drive to improve the chances of people with mental health problems gaining access to paid employment. Although this is challenging, individuals may have different vocational aspirations and there is more than one route towards achieving these.

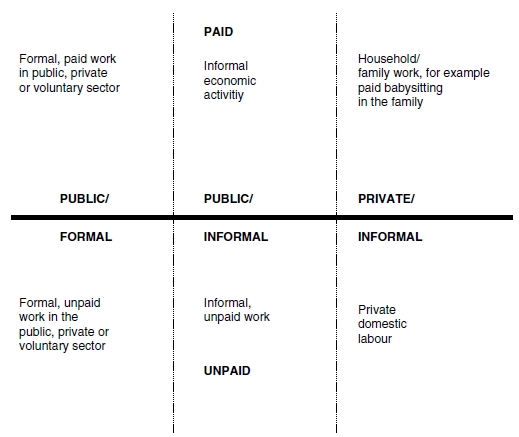

Taylor (2003) takes Glucksmann’s TSOL (1995) and develops it to provide a framework for understanding work (see Figure 10.2). This begins with the assumption that work or productivity is an activity that involves the production of goods for use by others, provides a service to others or can be performed by someone other than the one benefiting from it (Taylor, 2003). It then conceptualises work within its social context, through identifying different sectors within society, where these activities could take place. Private, public, formal and informal aspects of work are acknowledged and situated on a continuum, which indicate that they are not distinctly separable from one another. Within each of these sectors, one can further be doing either paid or unpaid work.

Plotting the different sectors creates a visual representation of the broad spectrum of sectors where work can take place. When an individual’s work activities are mapped within this framework, the interconnections between the different sectors become more evident (Taylor, 2003). In the context of mental health practice, the classification system could help service users to identify in which sector they are currently working and how they could move to another sector if they wished. It becomes possible to identify how skills can be transferred and to recognise how their current productive activity has meaning within a social context.

Figure 10.2 The organisation of labour in society. With permission from Taylor (2003).