OBJECTIVES

Objectives

Define the terms vulnerable populations, health disparities, and health equity.

Distinguish among differences in health, health disparities, and health-care disparities.

Understand the relationship between social vulnerability and health disparities, and the pathways mediating this association.

Recognize the ethical and human rights principles underlying efforts to achieve health equity

Identify actions health professionals may take to change the social conditions that create vulnerability and produce health disparities.

INTRODUCTION

“Vulnerable” derives from the Latin word for wounded. Populations can be vulnerable for a variety of reasons. In this chapter, we focus on populations that are wounded by social forces that place them at a disadvantage with respect to their health. Vulnerability is visible in the variation across social groups in levels of resources and social influence and acceptance, as well as in the incidence, prevalence, severity, and consequences of health conditions.

This chapter provides an overview of the concept of vulnerability. It begins by introducing the notion of health disparities, distinguishing it from simple differences in health, and defining the closely related concept of health equity. It describes evidence of health disparities, particularly by socioeconomic status (SES) and race/ethnicity. It then discusses conceptual models for understanding the pathways between social vulnerability and poor health status. It concludes by suggesting that health professionals have a responsibility not only to develop their skills to respond effectively to the health-care needs of vulnerable patients but also to take action to change the fundamental social conditions that produce vulnerability.

WHAT ARE HEALTH AND HEALTH-CARE DISPARITIES?

Webster’s dictionary defines disparity as a difference. “Difference” sounds like a neutral concept. It may seem logical that different people have different states of health, requiring different kinds and quantities of care. For example, elderly people are expected to be less healthy than young adults. People who ski are more likely to suffer leg fractures than people who do not.

Concern for health disparities is not about all differences in health, but rather about a subset of differences that are avoidable and suggest social injustice. Although few readers of this book probably were moved to righteous indignation by the health differences cited in the example of skiers and more frequent broken bones, the following observations are likely to prompt qualitatively different reactions: A baby born to an African-American mother in the United States is more than twice as likely to die before reaching her or his first birthday as is a baby born to a white mother.1 A World Bank study of 56 countries revealed that, overall and within virtually every country, infant and child mortality were highest among the poorest 20% of the population and lowest among the best-off 20% of the population; the disparities were large in absolute as well as relative terms.2

“Health disparities” is a shorthand term denoting a specific kind of health difference between more and less privileged social groups. It refers to differences that adversely affect disadvantaged groups that are systematic and persistent, not random or occasional, and that are at least theoretically amenable to social intervention. The social groups being compared are differentiated by their underlying social position, that is, by their relative position in social hierarchies defined by wealth, power, and/or prestige; this includes socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, gender, and age groups and groups defined by disability, sexual orientation or identity, or other characteristics reflecting social privilege or acceptance.3,4,5

Disparities in health care, as opposed to disparities in health, refer to systematic differences in health care received by people based on these same social characteristics. Although disparities in health care account for only a relatively small proportion of disparities in health, they are of particular importance to health-care providers and are discussed in detail in the next chapter.

For individuals concerned about vulnerable and underserved populations, one overarching objective is eliminating health disparities. A slightly different way of framing this aspiration is to state that the goal is to achieve health equity. This frames the objective as a positive one (achieving equity) rather than a negative one (eliminating disparities). This approach mirrors defining health as a positive state of well-being and not just the absence of disease. Health equity may be understood as a desired state of social justice in the domain of health, and health disparities as the metric used to measure progress toward this state. A reduction in health disparities is evidence of making progress toward greater health equity.6

ROLE OF SOCIOECONOMIC CLASS AND RACE/ETHNICITY IN HEALTH DISPARITIES

Profound and pervasive disparities in health associated with a range of socioeconomic factors such as income or wealth, education, and occupation have repeatedly been documented in the United States and globally.2,7,8,9 Despite ongoing debates about whether causation has been definitively established, considerable evidence has accumulated demonstrating, at a minimum, the biological plausibility of those associations.10,11 Similarly, virtually wherever data on health according to race or ethnic group have been measured, racial or ethnic disparities in health also have often been observed; these disparities sometimes, but not always, have disappeared or been markedly reduced once socioeconomic and other contextual differences have been accounted for.12,13,14

Social class shows a strong association with health and longevity. Higher SES provides individuals with more material, psychological, and social resources, which can benefit their health. There is no standardized method for defining or measuring social class in the clinical setting, and this information is not routinely collected as a part of health-care encounters. Some of the typical dimensions of social class used in research studies include occupation, income, and education level, which are all components of what is generally referred to as socioeconomic status.

Some of the most compelling evidence about the association between SES and health comes from the Whitehall study in the United Kingdom. This research on British civil servants demonstrated a linear association of higher occupational grade with lower 10-year mortality.15 This was a striking finding because significant differences in mortality occurred in a population in which all participants were employed and had health-care coverage. Despite the relative homogeneity of the group, those in higher occupational grades had significantly lower rates of a number of diseases as well as lower mortality. These differences remained 25 years later, even after some of the civil servants had retired from their jobs.16 A similar SES and health gradient has been observed in the United States. A 2010 study using national data observed stepwise incremental gradients of health improving as either income or educational level rose, for scores of indicators across the life course.8

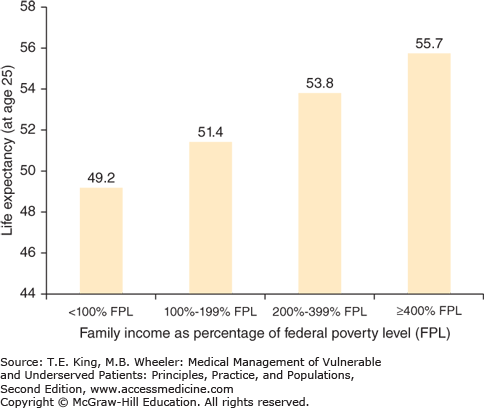

Analyses of the SES gradient generally reveal a sharp drop in mortality as income increases from the most extreme categories of poverty toward more moderate poverty, and a continued but more gradual drop in mortality as incomes rises above this moderate poverty level. The National Longitudinal Mortality Survey in the United States showed a difference of more than 6 years of life expectancy at age 25, between those who were poor and those with incomes more than four times the poverty level; there was a 2-year difference in life expectancy at age 25 between those with intermediate-level incomes (200–399% of poverty) and the higher-income group (Figure 1-1).8

Figure 1-1.

Family income and life expectancy at age 25 in the United States. This figure describes the number of years that adults in different income groups can expect to live beyond age 25. For example, a 25-year-old man with a family income below 100% of the federal poverty level can expect to live 49.2 additional years and reach an age of 74.2 years. (Source: CDC/NCHS, National Health Interview Survey Linked Mortality File, 2006. National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States 2011: With Special Feature on Socioeconomic Status and Health. Hyattsville, MD: 2012. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/2011/fig32.pdf.)

Above and beyond one’s own economic status, there is some evidence that the distribution of income across a population makes a difference. Although still being debated, income inequality itself may be bad for people’s health, irrespective of the average overall standard of living in a society. As discussed in Chapter 7, cross-national comparisons indicate that nations with less income inequality have better overall health indicators than nations at a comparable level of economic development with more unequal income distribution.17

Wealth is another measure of economic status. Wealth includes not just income, but also the value of assets such as home ownership, real estate, and investments—assets that often accumulate among families over generations. Wealth tends to have an even more inequitable distribution across a population than does income.

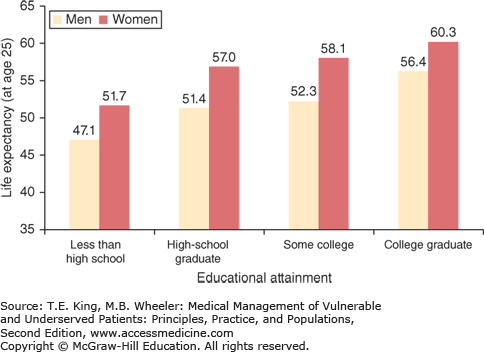

In contrast to the relationship between income and health, which demonstrates a continued drop in mortality as income increases (albeit with a sharper drop in the lower portion of the distribution), the association between mortality and education is more discontinuous. For all-cause mortality and each of the specific causes, the death rates are lower for those with more education (Figure 1-2). To the extent that education provides information, knowledge, and skills that improve health, each additional year of education should contribute somewhat equally to improved health. However, educational attainment also serves a credentialing function. As a result, there is a greater benefit of achieving years of schooling that result in a degree or credential than of additional years that do not. Thus, the benefit of completing the 12th year of schooling, which results in a high school degree, is greater than the benefit of completing any other single year of high school (referred to as the “sheepskin” effect).

Figure 1-2.

Educational attainment and life expectancy at age 25 in the United States. This figure describes the number of years that adults in different education groups can expect to live beyond age 25. For example, a 25-year-old man with a high school diploma can expect to live 51.4 additional years and reach an age of 76.4 years. (Source: CDC/NCHS, National Health Interview Survey Linked Mortality File, 2006. National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States 2011: With Special Feature on Socioeconomic Status and Health. Hyattsville, MD: 2012. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/2011/fig32.pdf.)

The data linking education and health can more clearly be interpreted as a causal effect of education and health than is the case for income and health. While poor health can reduce one’s income,18 education occurs earlier in life than do most serious diseases, and this temporal ordering provides a strong rationale for attributing the association to the impact of education on health.

Data in the United States on SES and health have been limited. While public health monitoring and epidemiologic surveys frequently collect information on race and ethnicity, they less often include information on income or education. Until recently, death certificates had only data on race and ethnicity, but now include information on education but not occupation, income, wealth, or other SES variables.

Race and ethnicity often are combined and referred to as one concept. Nevertheless, the concept of race as commonly used tends to evoke differences in skin color and other superficial secondary characteristics, whereas ethnicity incorporates the concept of culture.19

The health implications of classification of both racial and ethnic groups derive primarily from the social construction and impact of being labeled as belonging to one or another group. Apart from a small number of genes that code for skin color and other superficial secondary characteristics, and a few genes that are linked to geographic origin which confer risk for specific diseases, there is little biologic basis for health disparities among racial and ethnic groups. Advances in genomics have exposed the concept of race as predominantly a social construct, rooted in historical biases and social stratification based on ancestry and superficial phenotype rather than emanating from fundamental genetic differences among populations perceived to be of different “races.” There is no gene or set of genes that are exclusive to one race and that can be used to define those belonging to a race. Stated another way, one cannot look at a person’s DNA and tell definitively that she or he is Asian, African American, Latino, or white. The genetic variation among people within a racial and ethnic group is much greater than the variation across groups.20

Despite the lack of definitive genetic determinants, race and ethnicity have important influences on health. Based on historical conventions, US federal agencies use a two-item approach to classification. The first item is considered to represent race, and includes five major groups: African American or black, American Indian or Alaska native, Asian, native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, and white. The second item is considered to measure ethnicity, and consists solely of a dichotomous categorization of Hispanic or non-Hispanic. In our view, such categorical distinctions between the concept of race and ethnicity are an oversimplification of this socially defined construct, and we use the term “race–ethnicity” to communicate a more holistic notion of this concept.

Disparities by race–ethnicity are present in the United States for such diverse health indicators as infant mortality, cancer mortality, coronary heart disease mortality, and the prevalence of diabetes, HIV infection, or stroke (Table 1-1). Two clear observations can be made about these health outcomes categorized by race and ethnicity. First, African Americans experience the greatest morbidity and mortality on every reported indicator, and the gap often is substantial. For example, African Americans experience 12.7 deaths for every 1000 live births, compared with Asian or Pacific Islanders, who experience 4.5 deaths. Second, no other group shows consistently poor health outcomes across all indicators. Whites show poorer outcomes than groups other than African Americans on many of the reported health indicators (e.g., overall cancer mortality). American Indians and Alaska natives have the second highest rates of infant mortality, and Hispanics or Latinos have the second highest prevalence of diabetes. Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders show the most favorable profile.

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health Condition and Specific Example | White | Black/African American | Hispanic/Latino | Asian and Pacific Islander | American Indian and Alaska Native |

| Infant mortality: rate per 1000 live births | 5.5 | 12.7 | 5.6 | 4.5 | 8.4 |

| Cancer mortality: rate per 100,000 | 173 | 206 | 120 | 108 | 158 |

| Lung cancer mortality: rate per 100,000 | 49 | 52 | 21 | 25 | 40 |

| Female breast cancer mortality: rate per 100,000 | 22 | 31 | 15 | 11 | 15 |

| Coronary heart disease: mortality rate per 100,000 | 118 | 141 | 87 | 67 | 92 |

| Stroke: mortality rate per 100,000 | 38 | 56 | 30 | 32 | 30 |

| Homicides, per 100,000 | 2.6 | 19.9 | 6.6 | 2.2 | 9.0 |

| HIV infection: prevalence per 100,000 adults | 17 | 128 | 50 | 15 | 32 |

| Diabetes: prevalence per 100 adults | 6.8 | 11.3 | 11.5 | 10.2 | DSU |