4

4

When Are Computed Tomography Scans and Skull

X-Rays Indicated for Patients with Minor Head Injury?

BRIEF ANSWER

The need for a computed tomography (CT) scan varies with injury severity. CT scanning should always be considered for mild or moderate head injury, but it is indicated only rarely for minimal head injury. Skull x-rays are seldom indicated for the evaluation of traumatic brain injury.

Background

Skull radiography has always been a questionable tool for the diagnosis of intracranial hematomas. The relationship between skull fractures and intracranial lesions is indirect, and the yield of routine skull radiography for minor head injury is low. Authorities have sought for years to limit its use. In contrast, a CT scan is quite accurate for detecting traumatic intracranial lesions. Although urgent CT scanning has long been routine for severe head injuries, concerns about price and availability have limited its use in minor head trauma.

There appears to be a wide range of risk of intracranial sequelae among patients with minor head injury. We have divided minor head injury into three subcategories, based on relative risk of intracranial injury. Table 4-1 shows the categories, their definitions, and relative incidences. We recently summarized the reasons for including patients with Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) scores of 13 in the moderate head injury group.1

Literature Review

Class I evidence is quite sparse. There are very few prospective surveys and no controlled studies of any kind. At best, we can estimate the risks of intracranial lesions from pooled natural history data (mostly class III and some class II evidence) and compare the historical accuracy of different management schemes for the timely diagnosis of lesions. The observed outcomes of missed intracranial lesions in minor head injury populations allow a fair comparison of these management strategies. For the purposes of this chapter, we define an adverse outcome for a surgical lesion as a Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) score of severe disability or worse at 6 months. Adverse outcome for a nonsurgical lesion is less severe and is defined as subsequent return to the emergency department (ED) because of continued symptoms.

It is intuitively obvious that the risk of harboring a dangerous intracranial lesion is relatively low in minimal head injury and high in moderate injury. It is in the mild cases that the incidence of lesions and hence the indications for CT scanning are closest to threshold. Detailed analysis of this particular group would be most helpful in resolving differing opinions about the indications for scanning.

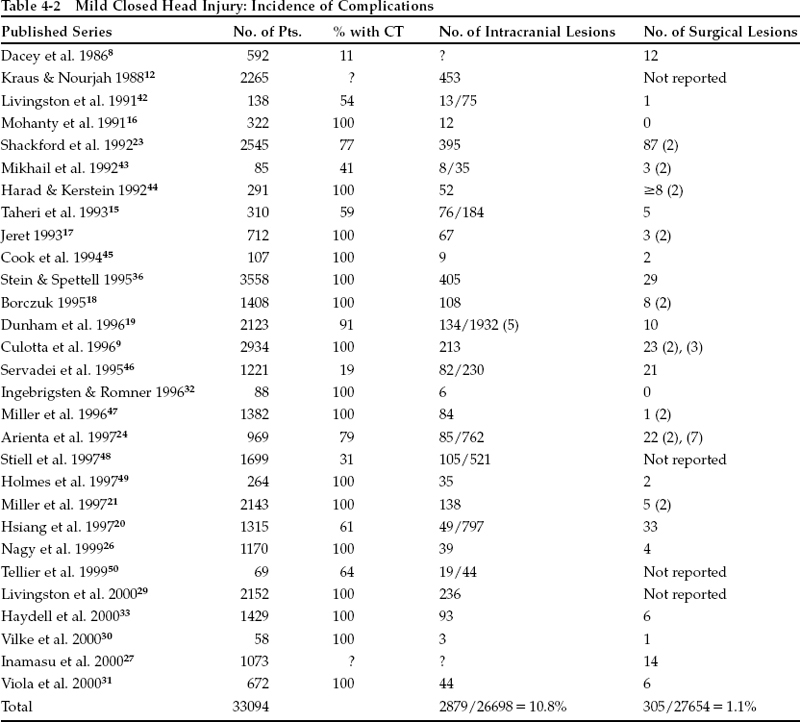

Table 4-2 reviews the evidence on the incidence of intracranial lesions in minor head injury and what proportion of these lesions require surgery. “Surgical” lesions are defined as evacuated hematomas or neurologic deterioration that caused an intracranial pressure (ICP) monitor to be inserted; elevation of fractures and scalp debridement are excluded. Variation exists among the patient populations studied in the quoted series (some include only GCS scores of 15, etc.), but the total of over 30,000 patients is large enough to minimize bias introduced by any single study. Although there has been considerable disagreement on how to interpret these figures, the incidence is remarkably consistent from study to study. We have chosen to compare the four alternative strategies for managing mild head injury suggested in the literature. These include universal admission (admit all to medical/surgical floor for 24 hours; CT only if condition worsens or symptoms persist),2 prolonged ED (6-hour observation in ED; admission and CT only if condition worsens or symptoms persist),3 skull x-ray screen (if fracture found, CT and admission; otherwise, discharge from ED with instruction sheet),4 CT screen (CT all; discharge from ED with instruction sheet if normal).5

Table 4-1 Classification of Minor Closed Head Injury

| Category | Definition | Relative Incidence (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Minimal | Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score = 15, plus no loss of consciousness (LOC) or amnesia; no neurologic deficit | 82.2 |

| Mild | GCS score = 14; or GCS score = 15 with brief (<5 minute) LOC, amnesia, or impaired alertness or memory | 15.1 |

| Moderate | GCS score = 9 to 13; or prolonged (>5 minute) LOC or focal neurological deficit | 2.7 |

Source: Stein & Spettell.36

Pearl

Proposed strategies for managing mild head injury have included hospital admission for all patients, prolonged observation in the ED, skull radiography of all patients as a screening technique, and CT scanning of all patients.

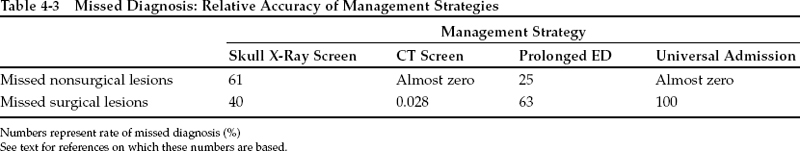

Table 4-3 summarizes the evidence regarding the diagnostic accuracy of each management strategy. An entry of “almost zero” reflects a lack of documented diagnostic failures for a particular category; in terms of adverse outcomes or additions to baseline costs, it reflects a lack of unfavorable consequences. For the purposes of calculation, these categories count as rates of 0%. In a meta-analysis of the value of skull radiography in minor closed head injury (CHI), Hofman and associates6 estimated that routine skull films would have missed 61% of intracranial hemorrhages. In another report, Miller et al7 found that plain radiographs showed no fracture in 40% of patients whose missed hematomas later required evacuation (class III data). Although there have been a few case reports of surgical intracranial hematomas appearing after normal initial CT scans in mild CHI, only seven cases are recorded among the almost 25,000 scanned patients reported in the published series (class III data).8,9 This yields an incidence of missed surgical lesions by CT screen of 0.028%. In a large series of pediatric patients with head injury, 63% of surgical lesions were not diagnosed within 5 hours of injury (class III data).10 Prolonged observation in the ED would likely fail to diagnose them. We have observed that ~25% of patients harboring nonsurgical lesions become more symptomatic after 6 hours and would be “missed” by prolonged ED observation (Stein SC, unpublished data).

Prompt identification and evacuation of hematomas may prevent adverse outcomes (class III data),11 some of which may be attributed to missed lesions. Regarding the consequences of missed lesions, Miller and associates7 reviewed a series of patients with normal GCS scores who subsequently underwent operations for acute intracranial hematomas. The proportion of patients with poor outcomes was identical whether patients were observed until transfer to a neurosurgical unit or whether they were discharged and subsequently had to be readmitted (class III evidence). Hence the diagnosis can be considered to have been “missed” in all universal admission patients. Of the more than 2000 mild head injuries reported by Kraus and Nourjah,12 57% spent at least 2 days in the hospital; it could be argued that a similar proportion of patients with nonsurgical lesions would likely return to the ED for continued symptoms.

Pearl