Chapter 7 White Matter Diseases

White matter diseases are heterogeneous conditions linked together because they involve the same real estate. Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging is quite sensitive and, when combined with age and other pertinent clinical information, provides a reasonable amount of specificity with regard to white matter disease. We are going to start by dividing white matter diseases into demyelinating and dysmyelinating diseases (Box 7-1).

Box 7-1 Classification of White Matter Diseases

SECONDARY DEMYELINATING DISEASE

TOXIC

Demyelinating disorders have a common inflammatory component that injures and, in some cases, destroys white matter. Keep in mind, the white matter starts out normal and is then injured by the particular pathologic process. The oligodendrocyte is the cell responsible for wrapping the axon concentrically to form the myelin sheath, and although we speak of white matter diseases as those that affect myelin, in actual fact, there is now a great deal of evidence that myelin is not the only brain tissue damaged in “demyelinating diseases”; axons and neurons are also commonly affected. Our appreciation of the nature of these disorders has improved dramatically with more precise histopathology and new MR methodologies. We can further divide these diseases based on their presumed etiology (Box 7-2).

Box 7-2 Demyelinating Diseases Categorized by Presumed Etiology

Dysmyelinating disorders involve intrinsic abnormalities of myelin formation or myelin maintenance because of a genetic defect, an enzymatic disturbance, or both. These diseases are rare, usually seen in the pediatric or adolescent population, and often are associated with a bizarre appearance on MR. Some diseases, such as adrenoleukodystrophy, have characteristics of both demyelinating and dysmyelinating processes (although in Box 7-1 it is operationally listed in the dysmyelinating category). The term leukodystrophy is used interchangeably with dysmyelinating diseases and represents primary involvement of myelin. For concerned clinicians-in-training, 99.9% of what you will see in an adult private practice of radiology, however, will be demyelinating disease.

PRIMARY DEMYELINATING DISEASE

Multiple Sclerosis

Clinical Criteria

The criteria accepted by the International Panel in 2005 has been adopted by the mainstream neurology community and is outlined in Table 7-1 and Box 7-3. It advances a greater role for MR imaging in supporting the diagnosis of MS and now requires radiologists to count lesions and to determine if they are infratentorial, supratentorial, or spinal; if they are juxtacortical; and if they enhance. MR is also used to demonstrate when lesions are distributed over time to differentiate MS from acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) and other monophasic diseases that have a different course and prognosis.

Table 7-1 International Panel Criteria (McDonald Criteria) for the Diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis

| Clinical Presentation | Additional Data Needed for MS Diagnosis |

|---|---|

| Two or more attacks; objective clinical evidence of two or more lesions | None |

| Two or more attacks; objective clinical evidence of one lesion | Dissemination in space, demonstrated by: |

| One attack; objective clinical evidence of two or more lesions | Dissemination in time, demonstrated by MRI, or second clinical attack. |

| One attack; objective clinical evidence of one lesion (clinically isolated syndrome) | Dissemination in space, demonstrated by: |

| Insidious neurologic progression suggestive of multiple sclerosis | One year of disease progression and dissemination in space, demonstrated by two of the following: • ≥Nine T2 lesions in brain, or four to eight T2 lesions in brain with positive visual-evoked potentials, or |

MR Findings

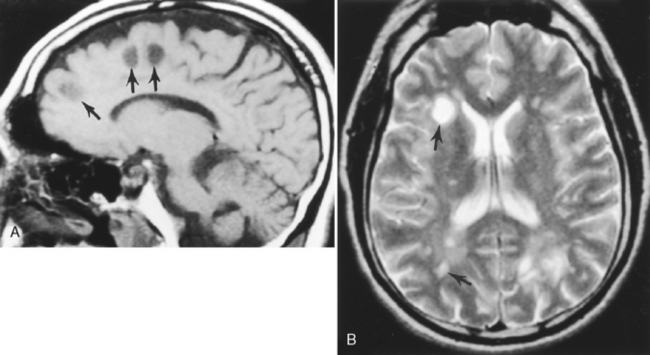

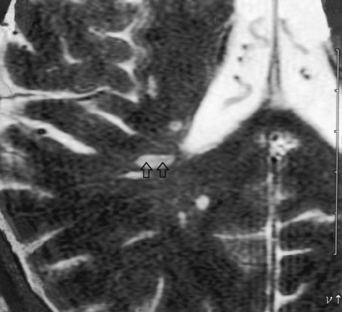

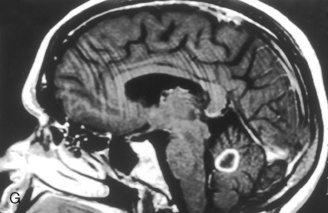

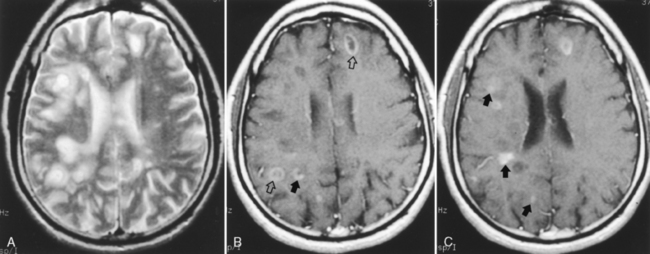

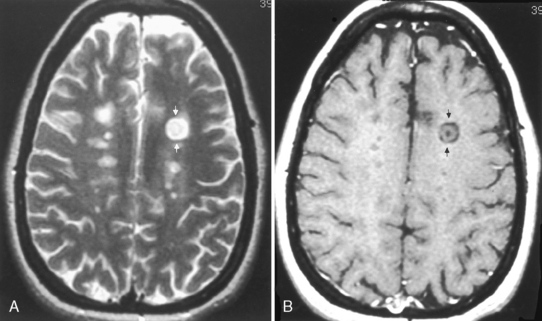

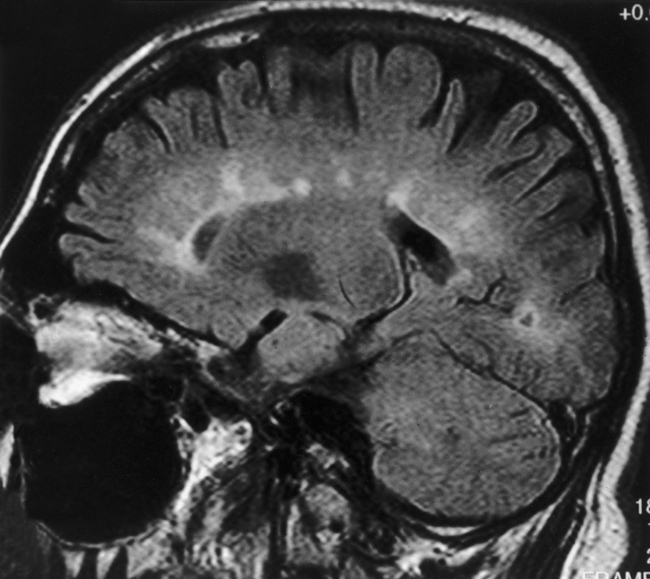

On T1WI, plaques are isointense or low-intensity regions, whereas on T2WI the lesions are high intensity (Fig. 7-1). The hypointense lesions on T1WI have been termed black holes and have been reported to be associated with areas of greatest myelin loss and to correlate with patient disability scores/clinical symptoms. On T2WI, tiny nodules or large confluent high-intensity lesions are seen. MS lesions have a predilection for certain regions of the brain, including the periventricular region, corpus callosum (best visualized on sagittal fluid-attenuated inversion recovery [FLAIR] or proton density-weighted images [PDWI]), subcortical region (best seen on FLAIR), optic nerves and visual pathways, posterior fossa (including the brain stem and cerebellar peduncles, best seen on T2WI), and cervical region of the spinal cord. However, MS lesions can and do occur in any location in the brain. This includes the cortex (6%), where white matter fibers track up to the superficial cortical cells, and the deep gray matter (5%). CAUTION: FLAIR imaging does not detect lesions in the posterior fossa, brain stem, and spinal cord as well as conventional T2WI. In addition, very hypointense lesions on T1WI may look similar to CSF on FLAIR; that is, not bright. High-intensity lesions at the callosal-septal interface (sagittal FLAIR) have been suggested to have 93% sensitivity and 98% specificity in differentiating MS lesions from vascular disease (Fig. 7-2). The shape of these MS plaques may be variable. However, ovoid lesions are believed to be more specific for MS. Their morphology has been attributed to inflammatory changes around the long axis of a medullary vein (Dawson’s fingers) (Fig. 7-3).

Figure 7-2 Sagittal FLAIR image with high intensity lesions emanating from the septal-callosal interface.

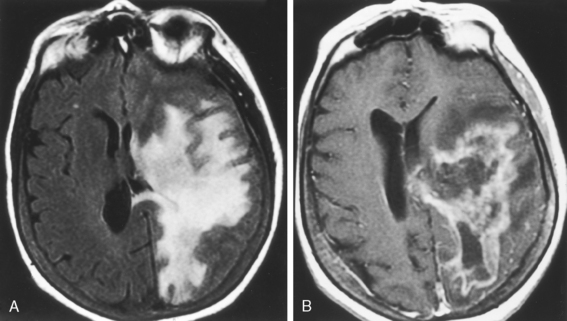

Lesions may display mass effect that can mimic a tumor (tumefactive MS) and have been associated with seizures (Fig. 7-4). Several hints aid in suggesting this diagnosis, including the history, which is usually acute or subacute in onset in a young adult, and other white matter abnormalities unassociated with the mass lesion (check the spinal cord) and the callosal-septal interface. Tumefactive MS lesions have a leading edge of enhancement and often an incomplete horseshoe-shaped ring of enhancement. Perfusion in tumors is usually increased and in MS it is normally not. Veins are displaced by neoplasms but course through MS lesions. There also have been rare reports of hemorrhage into demyelinating lesions, but this is more common in tumors and strokes. Some of the many faces of MS are displayed in Figure 7-5.

There is a significant incidence of high-intensity abnormalities in the brains of healthy individuals without MS. This number varies depending on the exact report and the cohort’s age. In one study of healthy volunteers, white matter abnormalities were noted in 11% of subjects age 0 to 39 years, in 31% age 40 to 49 years, 47% age 50 to 59 years, 60% age 60 to 69 years, and in 83% of those age 70 years and older. Rudimentary MR criteria may have a role in prioritizing differential diagnoses; however, with all of the caveats related to high-intensity abnormalities, the use of MR criteria alone is open to criticism and fraught with error. Most radiologists provide a broad disclaimer when identifying a few white matter lesions in a young patient with a nonclassical appearance, such as, “These lesions are nonspecific in appearance and may be seen with accelerated small-vessel ischemic disease, vasculopathies, migraine headaches, Lyme disease, and as the residua from inflammatory and traumatic insults to the brain.” No, it does not cover everything. If there is an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, include vasculitis, not just vasculopathy. Vasculitides (see Chapters 4 and 6) including primary angiitis of the central nervous system, polyarteritis nodosa, Behçet’s disease, syphilis, Wegener’s granulomatosis, Sjogren syndrome, and lupus should be in the differential diagnosis of MS both clinically and radiographically.

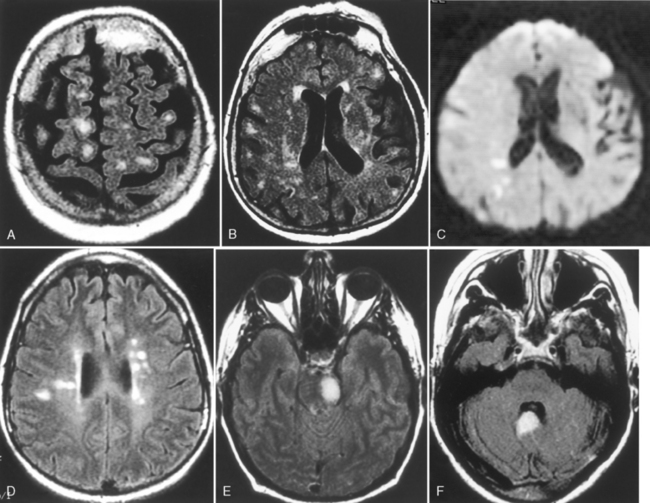

Enhancement in MS

The enhancement pattern of the initial lesion is usually in the shape of a nodule, which may be ovoid in appearance. Nodular enhancement can evolve to a ring or arc shape (Fig. 7-6). If lesions recrudesce, they usually have an arc or ring appearance. Many times the center of this type of lesion is lower intensity on T1WI. On T2WI, lesions generally wax and wane in size. Most often, one is left with a residual high-intensity lesion on T2WI. If a lesion is enhancing as a nodule for more than 3 months, be a little suspicious—it can happen, but consider other possible diagnoses. Cranial nerves (besides the optic nerve) can also enhance, but make sure the patient has MS (Fig. 7-7). Enhancement is more sensitive than either clinical examination or T2WI in detecting disease activity and potentially can separate clinical groups. The normal window of enhancement is from 2 to 8 weeks; however, plaques can enhance for 6 months or more. Enhancement cannot be viewed as an “all or none” phenomenon; rather it is dependent on the time from injection to imaging, the dosage of contrast agent, the magnitude of the blood-brain barrier abnormality, and the size of the space where it accumulates. Delayed imaging (usually 15 to 60 minutes after injection) increases the detection of enhancing MS lesions. Triple doses of gadolinium (0.3 mmol/kg) or a single dose (0.1 mmol/kg) with magnetization transfer (MT) (also see discussion in the New Methods section of this chapter) to suppress normal brain can increase the number of detectable MS lesions.

Normal-appearing White Matter

We have just covered combinations and permutations of visible lesions but the normal-appearing white matter (NAWM) is also abnormal. Yes, the term is quite relative. There are many new MR methods (see New Methods in this chapter) that clearly demonstrate that the NAWM in MS is not normal; that is, there are lesions that we cannot detect by conventional MR. This is important, because the extent of disease in MS patients is generally greater than the visible T2 lesion load. In addition, MS lesions tend to have fuzzy borders; that is, even the visible lesions have abnormalities that extend beyond the visible boundaries on T2WI.

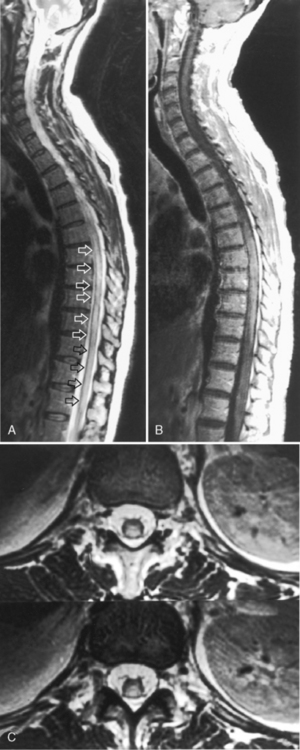

Spinal Cord Disease

Clinical Differential Diagnosis of Spinal Cord MS

When confronted with a clinical condition that is suggestive of MS and you see high intensity enhancing spinal cord lesions, what is the differential diagnosis? Multifocal, nonexpansile, single vertebral level, enhancing, and nonenhancing lesions should evoke MS and move on. However, if you have large lesions that stretch over many segments and expand the cord, include (1) vascular lesions, particularly dural arteriovenous malformation, producing venous hypertension and subsequent venous infarction; (2) collagen vascular diseases, such as lupus myelitis; and (3) other inflammatory diseases, such as sarcoid and ADEM. Other considerations also include intrinsic spinal cord neoplasms and infections, both viral (including human immunodeficiency virus [HIV]) and bacterial, which can all masquerade as spinal MS in its “transverse myelitis” pattern. An appropriate history, CSF analysis, and careful examination of the MR are important in differentiating these lesions. Subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord caused by vitamin B12 deficiency involves the spinal cord posterior columns symmetrically and is associated with a peripheral neuropathy. Box 7-4 lists the differential diagnosis of an enlarged spinal cord.

MS Syndromes

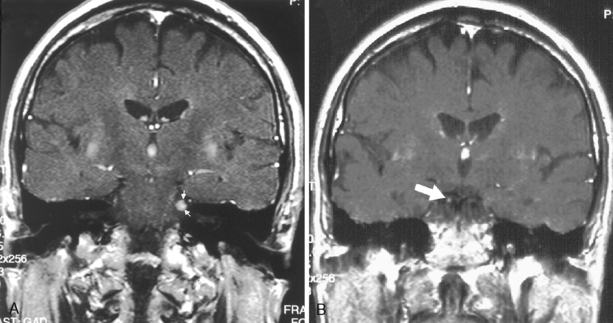

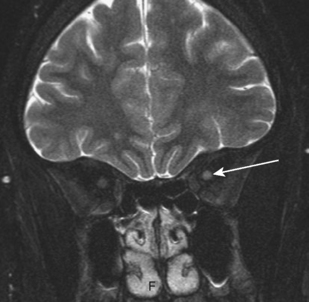

Many syndromes are associated with MS. Devic disease, or neuromyelitis optica (Fig. 7-8), represents either an acute variant of MS or a separate demyelinating disease. The disease consists of both transverse myelitis and bilateral optic neuritis (Fig. 7-9). Symptoms may occur simultaneously or be separated by days or weeks. The clinical manifestations can be severe.

Figure 7-9 Optic neuritis. The T2-weighted image shows bright signal within the left optic nerve (arrow).

Balo disease (concentric sclerosis) represents a histologic MS lesion with alternating concentric regions of demyelination and normal brain (Fig. 7-10). Diffuse sclerosis (Schilder disease) is an acute, rapidly progressive form of MS with bilateral relatively symmetric demyelination. It is seen in childhood and rarely after age 40 years. It is characterized by large areas of demyelination that are well circumscribed, often involving the centrum semiovale and occipital lobes. Marburg variant of MS is defined as repeated relapses with rapidly accumulating disability, producing immobility, lack of protective pharyngeal reflexes, and bladder involvement.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree