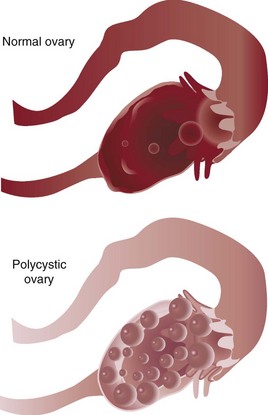

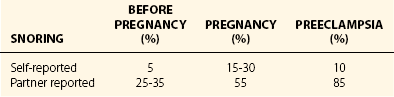

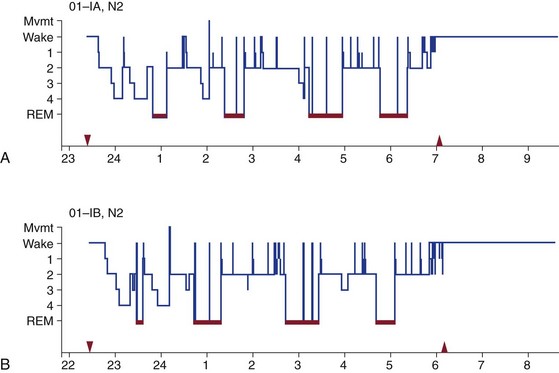

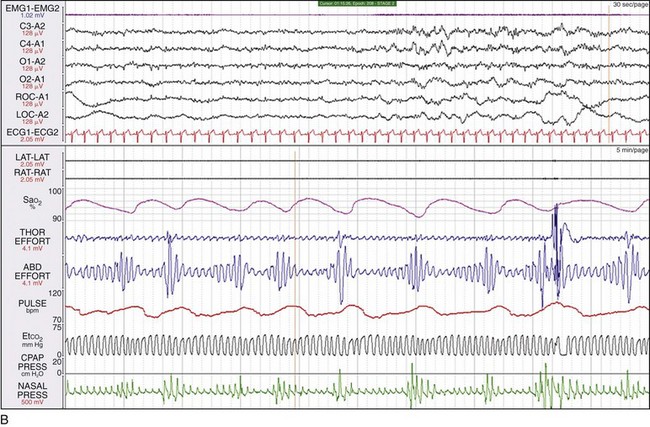

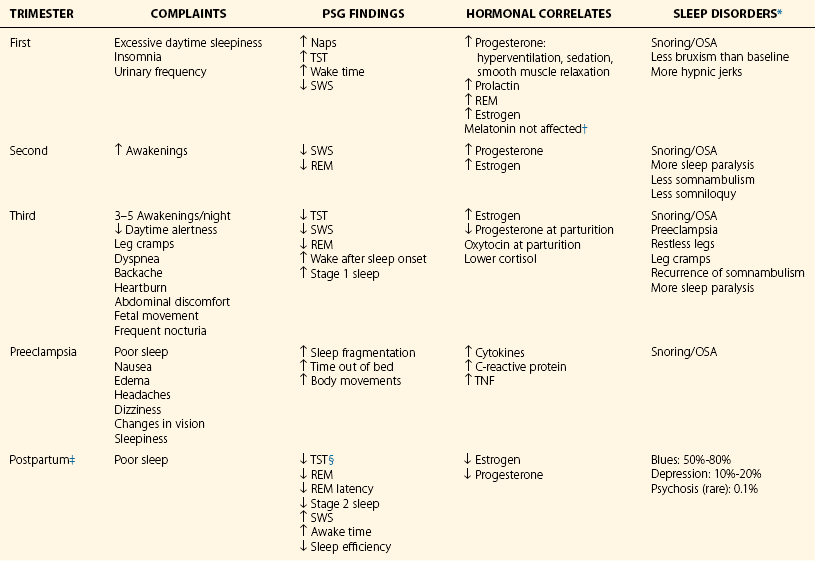

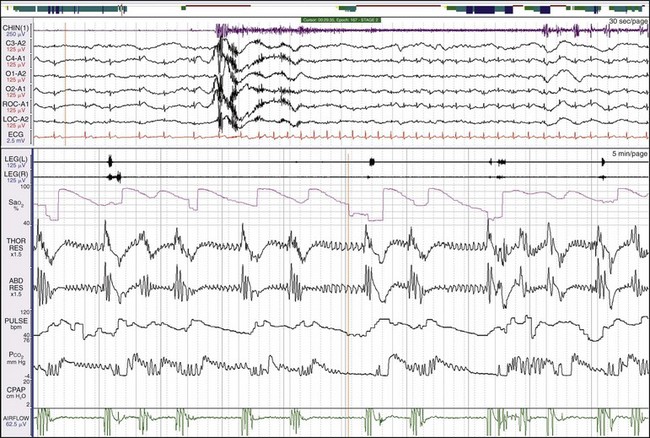

Chapter 16 16.1 The Menstrual Cycle Healthy menstruating women report more problems with their sleep during the premenstrual week and the first few days of menses compared with other days. Their sleep problems are likely because of menstrual cramps and the pain of dysmenorrhea, although little research has been done on possible mechanisms. Sleep problems may also be from rapid withdrawal of the sedating effects of progesterone before menses onset. Objective sleep measures in controlled laboratory settings, however, show little change in rapid eye movement (REM) and non-REM (NREM) sleep stages from one phase of the cycle to another; of course, only small numbers of women participate in these longitudinal studies. When ovulation has occurred, and the increased progesterone raises core body temperature during the luteal phase, a woman’s REM latency is often shorter compared with her own follicular phase (Fig. 16.1-1). Figure 16.1-1 Hypnograms from ambulatory polysomnography in the home setting. Evidence shows that women with premenstrual syndrome (PMS) have less slow-wave deep sleep than other women of the same age. Figure 16.1-1 depicts hypnograms for a woman with PMS. At each phase she had only 13% slow-wave deep sleep; note the earlier REM latency during the luteal phase (62 minutes) compared with the follicular phase (87 minutes). Oral contraceptives maintain low levels of hormones during the menstrual cycle, and in addition to preventing ovulation, this therapy may be useful for severe sleep complaints in young women. Polycystic ovary syndrome occurs in about 5% of young women and is usually diagnosed when infertility becomes a concern. In addition to the presence of bilateral polycystic ovaries (Fig. 16.1-2), these women often experience irregular and anovulatory menstrual cycles along with androgen excess with hirsutism and acne (Figs. 16.1-3 and 16.1-4). About half of this patient population is also obese and at risk for insulin resistance. They have lower sleep efficiency, with less REM and NREM sleep, and they are much more likely to experience sleep-disordered breathing and daytime sleepiness compared with ovulating women of similar age and body weight. It is likely that between 20% and 40% of obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome have sleep apnea. Figure 16.1-3 The periumbilical region of the abdomen of a woman with polycystic ovary syndrome shows male distribution of hair growth. Figure 16.1-4 A woman with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Baker, FC, Sassoon, SA, Kahan, T, et al. Perceived poor sleep quality in the absence of polysomnographic sleep disturbance in women with severe premenstrual syndrome. J Sleep Res. 2012; 21:535–545. Lee, KA, Baker, FC, Newton, KM, Ancoli-Israel, S. The influence of reproductive status and age on women’s sleep. J Womens Health. 2008; 17:1209–1214. Mokhlesi, B, Scoccia, B, Mazzone, T, Sam, S. Risk of obstructive sleep apnea in obese and nonobese women with polycystic ovary syndrome and healthy reproductively normal women. Fertil Steril. 2012; 97:786–791. 16.2 Pregnancy and Postpartum Blood volume, hormone effects, and physical changes during pregnancy affect a woman’s sleep. During the first trimester, with rapidly expanding blood volume and progesterone-induced hyperventilation, there is a sense of shortness of breath. The added estrogen increases pliability and hyperemia, causing nasal passages to become more collapsible. Both of these changes contribute to the heightened sensation of dyspnea. The added progesterone is also likely to increase daytime sleepiness and napping, thereby increasing overall total sleep time. Persistent nighttime or early morning nausea and vomiting of pregnancy can also worsen sleep, although the second trimester brings some normalization to total sleep time. Table 16.2-1 summarizes common complaints, polysomnographic findings, and sleep disorders found during the three trimesters of pregnancy. Frequent snoring affects fewer than 5% of nonpregnant women, but it affects 15% to 20% of pregnant women. A higher incidence of snoring has been reported in the second trimester. Table 16.2-1 Features of Sleep Disturbances in Pregnancy and Postpartum *Narcoleptic symptoms can continue during pregnancy. †β-Human chorionic gonadotropin, rennin, nitric oxide, interleukin-1, TNF, and interferon may also facilitate sleepiness. ‡Multiparous mothers with fewer symptoms compared with nulliparous mothers. §Mothers caring for premature infants with more waking after sleep onset and even less total sleep time. A higher risk of preeclampsia has been reported among frequent snorers (Table 16.2-2). Aside from systemic hypertension, pedal edema, and proteinuria, babies born to preeclamptic women who snore may be more likely to have intrauterine growth retardation and lower Apgar scores. Studies further document an increase in cytokine markers, tumor necrosis factor, and interleukin-6 among preeclamptic snorers. Few polysomnographic sleep studies have been done on women in labor, for obvious reasons (Fig. 16.2-1). When women expecting their first child were monitored with wrist actigraphy for five nights before the onset of labor, results were surprising. Sleep progressively deteriorates from an average of 7.5 plus 1.0 hours and 15% wake time to 4.5 plus 2.0 hours with about 30% wake time the night before the onset of labor and hospital admission. This also occurs to a lesser extent in women scheduled for induction of labor. Anxiety about labor may be a key factor. Having most of the active labor during the night may be related to depressed mood during the first few weeks after delivery. Figure 16.2-1 Postcesarean polysomnography (PSG) in a woman with apnea.

Women’s Health

Menstrual Cycle Sleep Changes

The patient is a 29-year-old woman with a history of premenstrual syndrome. A, Follicular phase (day 8 of the menstrual cycle), night 2 of polysomnography recording: total sleep time, 425 minutes; rapid eye movement (REM) sleep latency from stage 2 sleep, 87 minutes; REM sleep, 27%; stage 2 sleep, 52%; stage 3 and 4 sleep, 12.5%; sleep efficiency, 96%. B, Luteal phase (day 20 of the menstrual cycle), night 2 of polysomnography recording: total sleep time, 420 minutes; REM latency from stage 2 sleep, 62 minutes; REM sleep, 24%; stage 2 sleep, 53%; stage 3 and 4 sleep, 12.9%; sleep efficiency, 95%. Mvmt, movement.

Premenstrual Mood and Sleep

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

Because of embarrassment, this patient shaved her periumbilical hair.

A, Note the facial features (hirsutism and acne) characteristic of androgen excess. B, This polysomnogram segment shows severe sleep apnea in a 48-year-old woman who had symptoms of PCOS for more than a decade and who was first diagnosed with PCOS when assessed for sleep apnea. The patient was obese and had angina pectoris, arterial hypertension, and diabetes mellitus.

Sleep-Disordered Breathing

Labor and Delivery

This PSG fragment was taken from a 38-year-old woman immediately after cesarean delivery. She had a difficult pregnancy complicated by arterial hypertension, peripheral edema, and gastroesophageal reflux with a history of snoring, observed apnea, and daytime sleepiness. Immediately after the cesarean delivery, she was noted to have life-threatening hypoxemia. She had an apnea-hypopnea index of 167, and her oxygen saturation (SaO2) approached 40%.![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Women’s Health

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue