OBJECTIVES

Identify economic, social, and political causes of women’s health vulnerability.

Describe the increased burden of disease for women.

Review barriers to preventing unintended pregnancy.

Discuss innovative models for providing care to women.

Summarize strategies to help women use contraception successfully.

Ellen Reed is a 37-year-old woman with diabetes. She has three children and works two part-time jobs. Though she has health insurance coverage, she has difficulties navigating the system. The financial burden of paying for her many medicines is also prohibitive. Some months she has to forgo medications in order to pay for essentials for her family, like food and rent.

INTRODUCTION

A woman’s health and social position are intimately entwined. Social inequalities shape women’s illnesses and their options for medical care. Poor women, women of color, and elderly women are particularly affected by social disparities and their consequent impact on health.

Compared with men, women on average possess less social and economic power, are more limited in pursuing higher education and employment opportunities, and shoulder a higher burden of unpaid and hidden work (especially related to family care and community activities). In addition, women are more likely to work in low-wage, high-stress positions in the service industry. All of these inequalities increase women’s vulnerability to poverty.

Poverty, in turn, undermines health. Poor women are at increased risk for acquiring disease and have poorer health in general compared with women with greater economic power. Reproductive health in particular suffers in poverty. Women living in poverty are more likely to acquire sexually transmitted diseases and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). In some regions of the world, complications of pregnancy and childbirth claim the lives or well-being of a significant number of young women. Complications from disease progression (e.g., infertility secondary to untreated pelvic infection) are more prevalent for poor women who experience difficulties accessing health care. Additionally, because many poor women rely on government insurance for reproductive health care, poor women are most directly affected by the politicization of reproductive health care.

This chapter discusses factors that influence and contribute to women’s vulnerability, especially as it relates to their reproductive health. It concludes by offering strategies for improving reproductive health disparities with a focus on the United States. Issues related to lesbian health are discussed in Chapter 32.

WOMEN’S HEALTH: WHY ARE WOMEN VULNERABLE?

Women in the United States have a life expectancy of 5 years longer than men and lower age-adjusted death rates than men for 12 of the 15 leading causes of death.1 However, many women’s health needs are inadequately addressed.

Ellen is the sole breadwinner and caregiver for her family. Although she knows eating right and exercising are good for her health, she often lacks the time and energy to do either. She even finds it difficult to make time for appointments with her physician.

Women’s multiple roles in the family and workplace can make it difficult for them to prioritize their own health-care needs. Nearly one half (48%) of women aged 18–64 years in the United States have children younger than 18 years at home. Mothers bear a disproportionate burden of responsibility for housework, even if they also work outside the home, as more than two-thirds of them do.2 The majority of women with young children have primary responsibility for coordinating their children’s health care and missing work to care for a sick child. Low-income women are particularly affected by these multiple responsibilities.2

In addition to caring for young children, women are often called on to care for elderly or ill parents. These women are likely to have children of their own, work outside the home, and report the presence of a chronic disease themselves. Despite their own need for health care, up to 25% of women caring for elderly, disabled, or ill family members are uninsured. A stark example of how women’s health is threatened by their care-taking role was evident in the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, where women, as the care takers of sick family members, were disproportionately becoming infected and dying.

Last year, Ellen’s combined income from her two part-time jobs was $39,500 (the poverty level for a family of four is $23,850). She barely had enough money to purchase all the resources her family required to live and she never had any discretionary income.

In 2012, 15% of families in the United States, almost 46.5 million families, were considered poor. Of all family groups, poverty is highest among those headed by single women. In 2012, 30.9% of all female-headed families (4.8 million families) were poor, compared with 6.3% of married-couple families (3.7 million families).3 These figures are even more dismaying for women of color, with 51% of Latinos and 49% of African American female-headed households falling below the poverty line, compared with 39% of whites.4 Women experience increased rates of poverty compared with men throughout their lifespan. Even among the elderly, 13% of women over the age of 75 live in poverty, compared with 6% of men.5 Individually, women within families may also have less control over financial decisions.

Poverty influences women’s subjective and objective health experiences. Poorer women have worse self-rated health status and higher rates of many chronic illnesses, including arthritis, asthma, depression, diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and osteoporosis.6

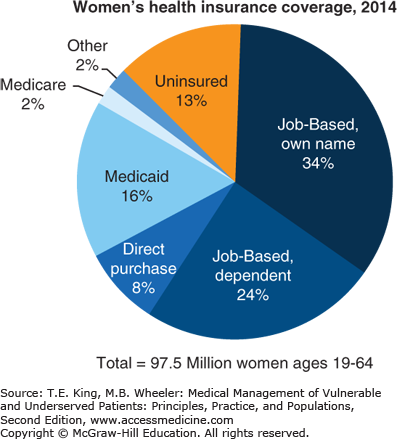

Women are more likely than men to be uninsured. In 2012, one-fifth of the US female population lacked health insurance. People without health insurance are more likely to postpone or forgo health care altogether. Women lack health insurance for a variety of reasons, but frequent reasons include Medicaid/Medicare (public insurance programs for the poor, sick, or elderly) ineligibility, lack of access to employer-sponsored programs, and inability to pay for health insurance (Figure 34-1). Historically, women comprised up to two-thirds of the Medicaid population, but have only been eligible for Medicaid if they are extremely poor or pregnant. If women did not fit into these categories, they were unable to qualify for Medicaid no matter how sick they were, or how much of a financial burden accessing care imposed. Medicaid is extremely important to women and children in the United States. Currently, Medicaid finances nearly half of all births in the United States (44.9%), and supports 75% of all publicly funded family planning services.7,8

Figure 34-1.

Health insurance coverage of women age 19 to 64. (Data from Women’s health insurance coverage fact sheet, Nov. 2015 Menlo Park, CA: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Accessed December 29, 2014. Available at http://kff.org/womens-health-policy/fact-sheet/womens-health-insurance-coverage-fact-sheet/.)

NOTE: For non-elderly women, “other” includes women who are covered through the military or are covered by private insurance for which the origin is unknown. Percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

The Affordable Care Act of 2010 has expanded the numbers of people who qualify for Medicaid, by increasing the minimum income requirement to 133% of the federal poverty level and eliminating qualifying conditions. Nevertheless, many states have not expanded Medicaid eligibility, despite the offer of federal funds for the expansion. This decision is projected to result in 2.4 million women being denied Medicaid who would otherwise have received coverage.9 In addition, for those who will qualify for expanded health insurance coverage, controversy still exists over provision of essential women’s health services such as contraception.

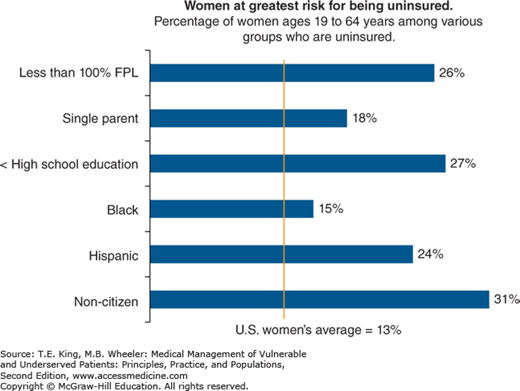

Women all over the world perform the majority of unpaid caregiving and uncompensated domestic chores, labor that often does not qualify for benefits and retirement support (and thus may incur risks beyond financial ones). For women participating in the paid labor force, many are low-wage workers in industries that expose them to risk of physical injury and do not offer benefits. In the United States, female sex, younger age, less education, and non-Caucasian ethnicity are risk factors for low-wage employment, poverty, and lack of health insurance coverage.10 Indeed gender, race, socioeconomic status (SES), and health status are intimately intertwined (Figure 34-2).

Figure 34-2.

Women at greatest risk of being uninsured. Women who are poor, single parents, women of color, who lack education, and non-citizen are at risk for being uninsured. The federal poverty level (FPL) was $19,790 in 2014 for a family of three. (Data from Women’s health insurance coverage fact sheet, Nov. 2015 Menlo Park, CA: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Accessed Dec. 29, 2015. Available at: http://kff.org/womens-health-policy/fact-sheet/womens-health-insurance-coverage-fact-sheet/.)

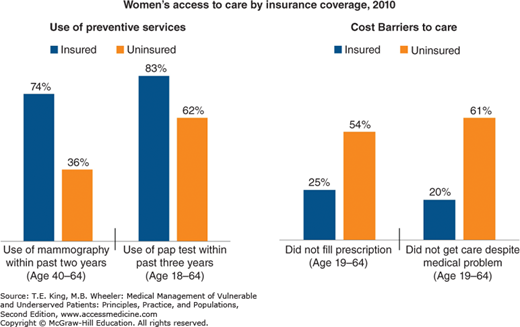

Uninsured women are more likely than insured women to postpone medical care, forego prescription medications, and delay or postpone important preventive care such as mammograms and Pap smears (Figure 34-3).10 They have more limited contraceptive options and the most efficacious forms of contraception are often cost prohibitive without insurance. When they become pregnant, women without insurance are less likely to receive prenatal care, and are at increased risk for poorer maternal and infant health outcomes. Women without insurance have poorer health outcomes in general compared with women with insurance. They are more likely to suffer from uncontrolled chronic medical conditions, and are more likely to die from cancers including breast and cervical cancer.6 Adequate health insurance coverage is necessary, but alone is insufficient for helping women achieve optimal health outcomes.

Figure 34-3.

“Barriers to health care based on insurance coverage.” The uninsured were significantly different from the insured on all measures at p < 0.05. (Data redrawn from Women’s health insurance coverage fact sheet, November 2013 Menlo Park, CA: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Accessed September 2, 2014. Women’s Health Policy Facts November 2013. Available at http://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/11/6000-11-womens-health-insurance-coverage-factsheet1.pdf.)

A variety of medical specialties attend to the health needs of women across their lifespan. Young women tend to identify generalists or obstetricians and gynecologists (ob-gyns) as their primary care providers, whereas older women are more likely to visit family physicians or internists. The care of women’s reproductive system is often separated from the care and management of women’s other health conditions, creating an imperative to establish relationships with multiple providers, or accept that some aspects of care may not be adequately addressed. This fragmented care is more common in women with limited insurance coverage.

Just as ob-gyns may fail to screen for hypertension or diabetes, other providers caring for women with chronic illnesses may fail to consider women’s reproductive lives in the management of their patients’ medical conditions. Without considering women’s reproductive lives, providers may inadvertently prescribe medications that affect the metabolism of contraception, or are teratogenic. Providers less familiar with reproductive health may also find it difficult to answer women’s basic questions about pregnancy options and abortion care services. In addition, the compartmentalization of women’s health care needs among specialties, and shortage of primary care physicians in general, may result in neglect of certain areas that do not have a clearly defined “home,” such as domestic violence and eating disorders.6

Racial and ethnic differences in mortality and health status are observed among women. Women of color are strikingly affected by poorer health outcomes throughout their lives compared to white women. Much of this risk is attributable to the effects of poverty on health, but a differential persists after controlling for income, suggesting that race and social inequality are independent predictors of women’s health status. African-American women have more complications of pregnancy and are also at higher risk for chronic illness.6 African-American and Latina women also suffer more than white women from diabetes and overall poor quality of health.6 Despite this higher burden of disease, women of color and poor women receive fewer preventive services and screening tests than white women, and are also less likely to be offered important health-care interventions.11,12 This results in higher mortality for African-American and poor women suffering from medical conditions including heart disease, cancer, and stroke.

Violence against women is alarmingly common. With epidemic proportions, it is a major public health and human rights issue. About 35% of women worldwide have experienced either intimate partner violence or nonpartner sexual violence in their lifetime. Low education, experiencing family violence as a child, and attitudes accepting violence and gender inequality are all risk factors for victimization. Political upheaval and displacement increase the rates of violence against women.13 In the United States, it is estimated that one in four women will experience domestic violence in their lifetime, and 1.3 million women are victims of intimate partner violence each year.14 Sexual assault is also common. Studies estimate that up to one in six women have experienced an attempted or completed rape.14 Women who have been involved in prostitution are at particularly high risk for emotional, sexual, and physical violence, but this risk factor rarely becomes known in the clinical encounter.15 Women who are the victims of violence also face high rates of physical and mental illness, including HIV (see Chapters 35, 36, and 43). Screening for intimate partner violence and referring to support services for women who are affected is an important part of the clinician’s role in addressing this issue.

Both women patients and their providers may harbor negative stereotypes that can hinder good care. Women patients may feel reluctant to report symptoms for fear of being thought of as “hypochondriacs.” When discussing sexual and reproductive health, women and their providers may feel embarrassed to discuss sexual practices or behaviors. Because taking a complete medical history is important for accurately diagnosing and treating diseases, it is important for health-care providers to create a judgment-free environment in the clinical setting.

Providers bring their own stereotypes about women patients to their interactions. Physicians may be more likely to see women patients as making excessive demands on their time, having complaints influenced by emotional factors, or having a psychosomatic component to their illness.16 These gender stereotypes can influence clinical care. Women tend to receive more prescriptions than men for the same problems, especially obesity, and are up to four times more likely than men to be prescribed activity limitations by their physicians, even with the same complaints, personal preferences, and illness behavior.17 Studies evaluating how providers care for patients presenting with chronic knee pain showed that physicians are less apt to recommend “aggressive” treatment options (e.g., surgical versus medical management) for women patients compared with male patients, despite evidence that women suffer from more intense pain than men.18 Providers should be mindful of their own biases and how these may influence the therapeutic relationship.

WOMEN’S REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH CARE

Ellen asks her provider about starting Depo Provera injections on two successive visits. Her physician, concerned about Ellen’s poor glycemic control and elevated blood pressure, defers the discussion until after she can review information about optimal contraceptive methods in the chronically ill. When Ellen is seen 2 months later, she is pregnant.

For many women, reproductive health-care issues predominate during their premenopausal adult lives. The need for safe and effective contraception, abortion, and prenatal care cuts across economic lines; yet, access to these services is strongly influenced by social position, geography, and political will. Limits on vulnerable women’s access span all areas of reproductive health care, including screening and treatment of common causes of infertility. Moreover, women’s sexual function, apart from their contraceptive needs, is rarely addressed and is poorly understood by most providers.19

Unintended pregnancy has significant implications for women’s health, the health of their families, and society. In the United States, around 6.6 million pregnancies occur each year, of which approximately half are unintended. In 2008, approximately 40% of these unintended pregnancies (excluding miscarriage) ended in abortion (1.1 million).20 Just over half of all publically funded births were the result of unintended pregnancy (1.1 million), and government expenditures on these births totaled $12.5 billion.21

Of the women who become pregnant unintentionally, approximately 46% report using contraception during the month they conceived; either the method failed or it was used incorrectly.22 In general, unintended pregnancies disproportionately affect women of low income, and African-American and Hispanic women.23 Women who experience unintended pregnancy are at increased risk of experiencing negative maternal and infant health outcomes compared with women who have successfully planned for pregnancy.24,25

Health disparities in unintended pregnancy can be understood by looking at three factors: patient preference and behaviors, health-care system factors, and provider-related factors.23 Health-care providers may contribute to disparities in a number of ways. For example, women with low literacy levels, or lack of English language proficiency, may find it difficult to understand much of the contraceptive information provided to them, and subsequently struggle to select a contraceptive method that best fits their needs.

Health-care providers play an important role in determining women’s success with contraception. Helping each woman to choose a contraceptive method that satisfies her unique individual needs and goals requires the clinician to engage in detailed patient education and to facilitate shared decision making. This includes understanding her experience with contraception and helping her identify priorities for a method, which can include efficacy, convenience, and side effects. Providing accurate information and reducing barriers to accessing contraception is essential to contraceptive success.

From the provider perspective, barriers to contraceptive success include limited time available in the clinical setting to address contraception in detail; not having a clear understanding of contraindications, efficacy, and side effects of individual methods; and inability to provide methods that require procedural skill, such as intrauterine or subdermal device placement. These issues are particularly relevant for women who live in areas without dedicated family planning clinic access. Women living in medically underserved communities, and who lack financial means to obtain health care elsewhere, may be forced to seek contraception in a setting that (1) limits their choices (particularly of long-acting methods), (2) is unable to provide contraceptives on site, or (3) uniformly links contraceptive access to preventive care (e.g., requiring a Pap smear before prescribing contraception).

Contraceptive knowledge in general varies by race and ethnicity, and influences contraceptive choice. Decreased contraceptive knowledge is associated with decreased utilization of the most effective contraceptive methods. Compared with white and black women, Hispanic women report the lowest levels of knowledge surrounding contraception. Women of color also are more likely to report increased skepticism surrounding various forms of contraception methods, and are more likely to hold beliefs that third parties are trying to limit their fertility.26 Thus, providers that appear to be biased toward one or a few particular methods (e.g., Intrauterine devices (IUDs) and implants) may be viewed with mistrust by patients. When performing contraceptive counseling, providers should be cognizant of these disparities in contraceptive knowledge and cultural attitudes surrounding contraception.

Systemic issues related to contraceptive failure include lack of funding for contraceptive care. For example, funding for Title X, a federal program that provides free or low-cost family planning care to many low-income women in the United States, has decreased by 58% since 1980, limiting contraception access for uninsured women. Even poor women with private health insurance may lack coverage, as only 24 states currently have laws that mandate contraception coverage for private insurance companies that provide prescription drugs and devices. The landscape of contraceptive access in the United States is changing, however (with the possible exception of religious employers claiming exemption). The Affordable Care Act, signed into law by President Obama in March 23, 2010, now requires all health plans to cover basic preventive services, including all FDA-approved contraceptive methods, with zero cost sharing or copay on the part of the beneficiary. Evidence has demonstrated that when all methods are offered free of cost, a large proportion of women choose highly effective contraceptives. In the Choice Project, a study of 10,000 women offered no-cost contraception, 67% chose intrauterine devices or implants.27

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree