World Aspects of Psychiatry

Mental disorders are highly prevalent in all regions of the world and represent a major source of disability and social burden worldwide. Treatments for all of these disorders are available and have been found to be efficacious in both developed and developing countries. However, mental disorders are remarkably undertreated worldwide, especially in low-income countries. National mental health policies are lacking in several countries, especially low-income ones. Resources for mental health care are scarce and unequally distributed. World psychiatry focuses on these and other issues such as the stigma attached to mental disorders, the relationships between mental and physical diseases, and the ethics of mental health care.

PREVALENCE AND BURDEN OF MENTAL DISORDERS WORLDWIDE

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that more than 25 percent of individuals worldwide develop one or more mental disorders during their lifetime. Among people seen by primary health care professionals, more than 20 percent have one or more current mental disorders. In a study carried out by the WHO at 14 sites in Africa, Asia, the Americas, and Europe, the average current prevalence of any mental disorder was 24 percent, without consistent differences between low- and high-income countries. The most common diagnoses were those of depression (average, 10.4 percent) and generalized anxiety disorder (average, 7.9 percent). Female rates were 1.89 times higher than male rates for depression, but male rates were higher for alcohol-related disorders, so that there was no sex difference in the proportion of people having at least one mental disorder. Physical ill health and educational disadvantage were both significantly associated with a diagnosis of mental disorder.

To quantify the burden of the various diseases and injuries, the WHO, in collaboration with the Harvard School of Public Health and the World Bank, introduced the disability-adjusted life year (DALY). DALYs for a given disease or injury are the sum of the years of life lost due to premature mortality plus the years lost due to disability for incident cases of that disease or injury in the general population. In the original estimates for the year 1990, mental and neurological disorders accounted for 10.5 percent of the total DALYs lost due to all diseases and injuries. The estimate for the year 2000 was 12.3 percent, with two mental disorders (depression and alcohol use disorders) and suicide ranking in the top 20 causes of DALYs for all ages.

In the estimates for the year 2005, mental and neurological disorders accounted for 13.5 percent of all DALYs in the world (27.4 percent in high-income countries, 17.7 percent in middle-income countries, and 9.1 percent in low-income countries), being the main contributor to burden among noncommunicable diseases (27.5 percent compared with 22 percent for cardiovascular diseases and 11 percent for cancer).

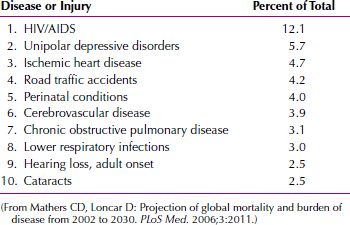

According to the updated estimates for the year 2030, mental and neurological disorders will account for 14.4 percent of all DALYs in the world and 25.4 percent of those due to noncommunicable diseases. Depression will rank number 2 in the percentage of total DALYs in that year (5.7 percent), following HIV/AIDS and preceding ischemic heart disease (Table 37-1). It will be number 1 in high-income countries (9.8 percent), number 2 in middle-income countries (6.7 percent), and number 3 in low-income countries (4.7 percent).

Table 37-1

Table 37-1

Leading Causes of Disability-Adjusted Life Year (DALYs) Worldwide As Estimated for the Year 2030

The WHO estimates that one of four families worldwide has at least one member with a mental disorder. The objective and subjective burden related to caring for people with severe mental disorders (in terms of disruption of family relationships; constraints in social, leisure, and work activities; financial difficulties; negative effect on physical health; feelings of loss, depression, and embarrassment in social situations; and the stress of coping with disturbing behaviors) has been reported to be substantial and significantly higher than that related to caring for people with long-term physical diseases such as diabetes and heart, kidney, or lung diseases. Cross-cultural differences have been reported in some dimensions of family burden.

Suicide is among the ten leading causes of death for all ages in most of the countries for which information is available. In some countries (e.g., China), it is the leading cause of death for people between 15 and 34 years of age.

According to WHO estimates, about 849,000 people died from suicide worldwide in the year 2001. In that year, the number of suicide deaths overtook the number of deaths by violence (500,000) and war (230,000). In 2020, approximately 1.53 million people will die from suicide worldwide based on current trends, and 10 to 20 times more people will attempt suicide. Reported suicide rates vary considerably across countries; for instance, annual suicide rates of 48.0 to 79.3 per 100,000 have been reported in many Eastern and Central European countries, and rates of less than 4.0 per 100,000 have been found in Islamic and several Latin American countries. More than 85 percent of suicides are reported to occur in low- or middle-income countries, but this figure may represent an underestimate due to the low reliability of official statistics in those countries: When surveillance with validated verbal autopsy was used in South India, the observed rates for suicide exceeded official national estimates tenfold. In the Asia-Pacific region, 300,000 cases of suicide per year are estimated to occur by self-poisoning with pesticides.

Suicide rates are higher in men than in women (3.2:1 in 1950, 3.6:1 in 1995, and an estimated 3.9:1 in 2020). China is the only country where suicide rates in women are consistently higher than those in men, especially in rural areas. Over the past few decades, suicide rates have been reported to be stable worldwide, but a rising trend among young men ages 15 to 19 years has been observed. A systematic review covering 15,629 cases in the general population worldwide estimated that 98 percent of those who committed suicide had a diagnosable mental disorder, with mood disorders accounting for 35.8 percent, substance-related disorders for 22.4 percent, personality disorders for 11.6 percent, and schizophrenia for 10.6 percent of cases.

TREATMENT GAP AND PROJECTED POPULATION-LEVEL TREATMENT EFFECTIVENESS WORLDWIDE

The efficacy of pharmacological and psychosocial treatments for mood, anxiety, psychotic, and substance-related disorders has been convincingly proved by clinical trials carried out in low- and middle-income, as well as in high-income, countries. However, the treatment gap is substantial for all mental disorders worldwide, particularly in low-income countries.

In the World Mental Health Surveys, failure and delays in treatment seeking were generally greater in low-income countries, older cohorts, men, and cases with earlier ages of onset. The earlier treatment contact of people with mood disorders might be partly due to the fact that these disorders have been targeted by educational campaigns and primary care quality improvement programs in several countries.

RESOURCES FOR MENTAL HEALTH CARE WORLDWIDE

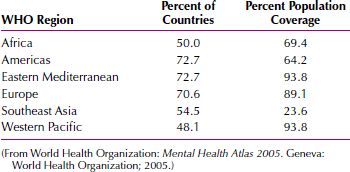

According to the Mental Health Atlas 2005, only 62.1 percent of countries worldwide, accounting for 68.3 percent of the world population, have a mental health policy (i.e., a document of the government or ministry of health specifying the goals for improving the mental health situation of the country, the priorities among those goals, and the main directions for attaining them). A mental health policy is present in 58.8 percent of low-income and 70.5 percent of high-income countries. In Africa, only 50 percent of countries have a mental health policy. In Southeast Asia, only 54.5 percent of countries have a mental health policy, and 76.4 percent of the population is not covered by such a policy (Table 37-2).

Table 37-2

Table 37-2

Presence of a Mental Health Policy in the Countries of Each Region of the World Health Organization (WHO)

Community care facilities exist in only 68.1 percent of the countries (51.7 percent of low-income and 93 percent of high-income countries). Only 60.9 percent of the countries report providing treatment facilities for severe mental disorders at the primary care level (55.2 percent of low-income and 79.5 percent of high-income countries). About one fourth of low-income countries do not provide even basic antidepressant medications in primary care settings. In many others, the supply does not cover all regions of the country or is very irregular. Because medicines are often not available in health care facilities, patients and families are forced to pay for them out of pocket.

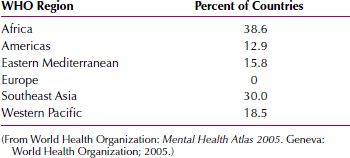

Whereas 61.5 percent of European countries spend more than 5 percent of their health budget on mental health care, 70 percent of countries in Africa and 50 percent of countries in Southeast Asia spend less than 1 percent. Out-of-pocket payment is the most important method of financing mental health care in 38.6 percent of countries in Africa and 30 percent of countries in Southeast Asia, but it is not the primary method of financing mental health care in any European country (Table 37-3). All countries with out-of-pocket payment as the dominant method of financing mental health care belong to low-income or lower middle-income categories, but almost all countries with social insurance as the dominant method of financing belong to high-income or upper middle-income categories.

Table 37-3

Table 37-3

Countries in Which Out-of-Pocket Payment Is the Most Common Method of Financing Mental Health Care in Each Region of the World Health Organization (WHO)

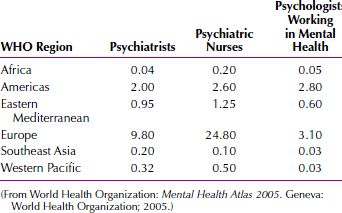

The median number of psychiatrists per 100,000 population ranges from 0.04 in Africa and 0.2 in Southeast Asia to 9.8 in Europe (Table 37-4). It is 0.1 in low-income countries compared with 9.2 in high-income countries. Two thirds of low-income countries have less than one psychiatrist per 100,000 population. Chad, Eritrea, and Liberia (with populations of 9, 4.2 and 3.5 million, respectively) each has just one psychiatrist per 100,000 population. Afghanistan, Rwanda, and Togo (with populations of 25, 8.5, and 5 million respectively) each has just two psychiatrists per 100,000 population. Large-scale migration of psychiatrists from low- and middle-income to high-income countries, as part of the larger picture of migration of health professionals in general, has been consistently documented. India and some sub-Saharan African countries are the most important contributors to the mental health workforce in the United Kingdom, although the United Kingdom has 110 psychiatrists per million population, but India has 2 per million and sub-Saharan Africa less than 1 per million. The median number of psychologists working in mental health care per 100,000 population ranges from 0.03 in Southeast Asia and 0.05 in Africa to 3.1 in Europe. Approximately 69 percent of low-income countries have less than one psychologist per 100,000 population. The median number of psychiatric nurses per 100,000 population ranges from 0.1 in Southeast Asia and 0.2 in Africa to 24.8 in Europe.

Table 37-4

Table 37-4

Median Number of Mental Health Professionals per 100,000 Population in Each Region of the World Health Organization (WHO)

From these figures, it is clear that resources for mental health care are grossly inadequate compared with the needs, and that inequalities across countries are substantial, especially between low- and high-income countries. Moreover, resources tend to be concentrated in urban areas, especially in low-income countries, leaving vast regions without any form of mental health care.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree