Your Approach to the Neurologic Patient

Where do You Start?

Where do You Start?

You need to have an approach to patients with potential neurologic problems that is both efficient and accurate. A reliable method of evaluating each problem will consistently provide needed direction and prevent unnecessary diversions. Read on to find out the best place to begin and how to proceed when faced with a neurologic problem.

“If it moves when it shouldn’t—it’s a seizure, but if it doesn’t move when it should— then it’s a stroke.”

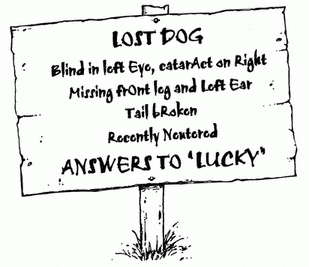

Using limited resources and skill, one can occasionally make a correct diagnosis by applying an oversimplified rule or two. When a medical student or resident was “lucky” enough to stumble across a correct diagnosis using such a rule, our former chairman, the sage Dr. Alan Follender, would wryly declare that “Even a blind three-legged dog occasionally finds a bone.” This “shoot from the hip” approach is certainly fast, but it will not be reliable on a day-to-day basis. This is especially the case when evaluating potential neurologic problems.

The basic four-step approach is preferred and essential to clinical neurology. Experienced neurologists go through the same steps

so seamlessly that the physician-in-training only sees the end product, a correct diagnosis. Using this systematic method initially requires some patience and practice. However, it reliably provides much-needed direction from the start, and helps save time, effort, and expense in the long run:

so seamlessly that the physician-in-training only sees the end product, a correct diagnosis. Using this systematic method initially requires some patience and practice. However, it reliably provides much-needed direction from the start, and helps save time, effort, and expense in the long run:

|

1. Where in the NeurAxis is the problem/dysfunction? (location)

2. What could the problem be at this level in this patient? (differential)

3. Which test would be useful to confirm this initial impression? (confirmation)

4. Is therapy indicated or available at this point for this problem? (treatment)

Answering these questions in sequence allows for a logical and efficient progression from the patient’s reported symptom(s) to the appropriate test or intervention/treatment. The organized clinician will waste much less time, order fewer superfluous tests, and avoid

unnecessary digressions. The majority of the information discussed in this book will direct the clinician in efficiently answering the first and most important (essential) question: Where is the problem?

unnecessary digressions. The majority of the information discussed in this book will direct the clinician in efficiently answering the first and most important (essential) question: Where is the problem?

“I have this guy in the ER who is weak. Should I get the brain CT with or without contrast?”

It has been said that our most expensive tool as physicians is the pen. Laboratory and/or radiologic testing should be based on a solid clinical impression derived from the interview and examination, not on a single reported symptom. This is especially important in neurology because a number of distinct areas (levels) may be tested by a variety of different technologies. Reflexively ordering a cranial CT scan on all patients with ill-defined subjective “weakness” will eventually lead to confusion (on the physician’s part), delayed care, and increased costs. Be sure not to skip step one!

“Should we start heparin on every patient with stroke?”

Years ago, one of our residents confidently declared that the use of intravenous heparin in patients with ischemic infarct of the brain was “part of the protocol.” This practice had, in fact, become so common that it was assumed to be part of a protocol or “cookbook” approach to managing stroke at our institution. However, we were never actually able to locate this written set of instructions, and medical research has since shown that the use of heparin in these cases is not usually indicated.

House officers as a group are often fond of written protocols. Indeed, they can provide a strong sense of certainty within an otherwise unpredictable and sometimes hectic environment. However, medical knowledge and technology have evolved so rapidly since the mid-1990s that many algorithms have quickly become obsolete. Technology and research have also allowed for a greater understanding of nervous system disease in recent years. One might assume that this has made clinical neurology easier or possibly less important. However, with more available tests and treatment options to choose from, the

clinical neurologic assessment is actually becoming more critical, not less so. We are now required to diagnose and treat certain patients much sooner (e.g., using thrombolysis to treat ischemic stroke) and in a more cost-effective manner than ever before (i.e., avoiding unnecessary tests).

clinical neurologic assessment is actually becoming more critical, not less so. We are now required to diagnose and treat certain patients much sooner (e.g., using thrombolysis to treat ischemic stroke) and in a more cost-effective manner than ever before (i.e., avoiding unnecessary tests).

This book is designed to help you become more efficient at identifying where the nervous system dysfunction is based on a limited number of important signs and symptoms (i.e., step one). To start using this method, all you need is a basic working knowledge of the nervous system. Anyone who has taken an anatomy course is familiar with each level of the nervous system (NeurAxis), including the cerebral hemispheres, spinal cord, and peripheral nerves. Using this knowledge as a foundation, you will quickly develop a framework to help sort through the levels efficiently based on available clinical information.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree