The experience of anxiety is a universal experience and has both psychological and physiological components. Anxiety is characterized by a variety of terms that refer to dystonic mood (e.g., fear, worry, apprehension) and is generally experienced in reaction to a specific fearful stimulus. The term fear is usually used when a specific threat is present. Anxiety is normally associated with stress but also has important adaptive functions. When excessive or prolonged, the experience of anxiety can stop being adaptive and become a source of distress or impairment that qualifies as an anxiety disorder.

One of the challenges for clinical definitions of these conditions is the common experience of fear and anxiety as a normative phenomenon as opposed to a clinical condition. Normative anxiety has strong developmental correlates beginning with issues of separation and stranger anxiety in very young children and then the development of various fears and concerns as children age. This trend continues with changes in the character of worry and anxiety manifestations in adolescents as cognitive capacities and social and personal expectations increase.

Probably the major point of differentiation of normal anxiety and anxiety disorder is the issue of impairment, that is, the condition must be of sufficient severity or intensity that it causes the child or adolescent some difficulties in daily functioning. The issue of “distress” is also included as a diagnostic feature but is, in many ways, much more difficult to operationalize, particularly in children.

Although frequently viewed as one of the anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) actually occupies a position somewhere between this and various other conditions (particularly tic disorders). The grouping with anxiety disorders here reflects a primary clinical awareness of the degree to which anxiety is a major aspect of the condition.

DEFINITIONS AND CLINICAL DESCRIPTION

Various different anxiety disorders are presently recognized. With some important exceptions, the approaches to diagnosis are similar in children and adults. These exceptions include separation anxiety disorder (SAD), which is essentially confined to children. A modification of the guidelines for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) makes it easier to diagnose the condition in children and adolescents. As

Krain et al. (2007) point out, the

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR) approach may well underestimate the importance of developmental differences in the ways anxiety is manifest. The utility of the current distinctions has been widely debated, particularly in light of frequent associations with other problems (e.g., mood disorders).

Table 12.1 provides an overview of diagnostic features for the anxiety disorders in children (OCD is discussed in the final section of this chapter).

Separation Anxiety Disorder

This condition is defined based on a judgment that separation anxiety (a normative developmental phenomenon manifest in stranger anxiety and attachment behaviors; see

Chapter 2) has become excessive and “developmentally inappropriate.” Typically, this takes the overt form of distress around separation and excessive worry about a major attachment figure, often the mother. Symptoms at separation include overt distress, repeated somatic complaints, nightmares, or sleep refusal. Referral is made when somatic complaints are prominent or when school refusal occurs. In the DSM-IV-TR, the condition must last at least 1 month and be a source of significant impairment. Onset typically is after age 6 years and before 18 years (i.e., in the developmental period but generally after the time when separation fears are normative). One argument for recognizing SAD as a category is the subsequent risk for panic disorder or agoraphobia later.

Social Anxiety Disorder (Social Phobia)

Social anxiety disorder is defined based on a persisting fear of exposure to unfamiliar persons in social situations. The term was added in DSM-IV-TR as an alternative to the term

social phobia to underscore the difference of this condition and the specific phobias. In social anxiety disorder, even the risk of exposure to a social situation can provoke severe anxiety or a panic attack. Commonly feared social situations include performance or public speaking as well as simply meeting new people or attending parties, meetings, and other social gatherings. The condition gives rise to significant problems because of attempts to avoid these situations and gives rise to preoccupations about rejection, negative judgments by others, and so on. Somatic symptoms can include heart palpitations, gastrointestinal complaints, and so forth; these can readily result in school refusal and other difficulties.

Toddlers who are behaviorally inhibited (withdrawing from novel or challenging situations) may be particularly likely to develop social anxiety disorder. As a result of failure to engage with others, individuals may develop noteworthy social deficits, and there is some suggestion (e.g., in family studies) of a connection to autism and related disorders that are characterized by marked problems in social interaction as well as anxiety.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

In this condition, excessive and uncontrollable worry leads to impaired daily functioning. In addition to extreme worry, there must be one somatic symptom, and the extreme anxiety must last for a period of at least 6 months. The anxiety often centers on issues of approval, events in the future, worries about lack of competence, or worries about new or unfamiliar situations. Although reassurance may be sought and may briefly seem to help, relief is brief. The somatic complaints are variable and can include the usual array of anxiety-related symptoms. Children with this condition frequently initially present to their pediatrician.

Various studies have revealed a strong association with depression. This has been taken to suggest that what is inherited may be a more general predisposition because, for example, adolescents with GAD often later develop depression.

Specific Phobia

In this condition, a marked and persistent fear is excessive or unreasonable and results in interference. Various objects or situations may be the source of the fear (e.g., heights, specific animals). Typically, features of anxiety, up to and including panic attack, are quickly provoked by exposure to the fear-producing stimulus. In children, the anxiety can lead to distress, tantrums, marked inhibition, or clinging to parents. Unlike adults with phobias, children do not always appreciate that the fear is abnormal or maladaptive. To make the diagnosis, the condition must be present for at least 6 months.

Various phobia types have been identified: one group centers on animals another on natural environmental phenomena, another on fears related to blood and injury, another on specific situations, and a final residual category includes the remainder. There has been speculation that these various types have evolutionary correlates.

Panic Disorder with or without Agoraphobia

Panic disorder is characterized by recurrent and unexpected panic attacks. Unlike panic attacks associated with phobias or other conditions, there is not a specific environmental event that triggers the attack. The period of intense fear and anxiety is associated with a minimum of four somatic or cognitive symptoms. For adolescents, the somatic symptoms might include palpitations, trembling, feeling faint or nauseous, or sweating or feeling short of breath; cognitive symptoms include fears of dying or losing one’s mind. When the patient is avoiding places or situations where he or she might have difficulty escaping (usually involving larger groups of people), a diagnosis of panic disorder with agoraphobia is made. The issue of differentiating cues and noncues or unexpected panic attack is needed to differentiate this condition from other anxiety disorders; but as a practical matter, this is not so easily accomplished in children. Panic attacks can also be associated with various medical conditions, including endocrine disturbances, seizures, vestibular problems, and cardiac conditions; accordingly, physical examination and appropriate laboratory testing may be needed.

Epidemiology and Demographics

Along with the mood disorders, to which they are closely related, anxiety disorders are some of the most common mental health problems in children and adolescents, impacting as many as one in five in this age group. Data from various epidemiologic studies randomly suggest that between 3% and almost 30% of children in community samples have some anxiety disorder. Rates vary significantly, reflecting differences in method and other factors.

One of the more robust differences is the consistent gender difference, with higher rates reported in females. This preponderance is noted even before puberty, even earlier than depression with the possible exception of GAD, which, similar to depression, becomes more frequent in girls during adolescence. SAD has an earlier onset than other conditions in this group, and its frequency markedly decreases over time. On the other hand, social phobia becomes more frequent in adolescents.

Lower socioeconomic status (SES) has been associated with both more normative fears and specific phobia. In other anxiety disorders, SES and cultural differences are not consistent. In addition to their frequency, these conditions can have multiple negative effects and are associated with an increased risk of problems in adulthood.

Etiology

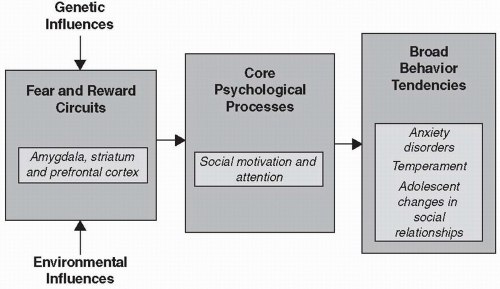

Etiologic models for anxiety disorders must encompass many different potential risk factors. These risks have complicated interrelationships with each other and may interact or predispose the developing child to increased vulnerability (or resilience). For purposes of discussion, these factors can be discussed separately, but as

Figure 12.1 indicates, there are actually complex interactions among them.

Work on the genetics of these conditions indicates a strong role for genetic factors, with increased risk for children whose parents have anxiety disorders and high rates of concordance in twin studies. It seems likely that these risk factors act by impacting specific psychological and developmental processes, which then put the child at increased risk. Studies have focused on specific genes, including the serotonin transporter gene (5HTT). In addition to genetic factors, environmental or experiential ones also have a major role in pathogenesis. One of

the complexities here is that parents who are anxious may behave in ways that facilitate the development of anxiety in children (through parenting style, modeling, and so forth). As with genetic factors, there are many potential mediators of these effects. Much interest has centered on disentangling the complex relationships of environmental and genetic vulnerabilities and the mediating events in pathogenesis.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access