Definition and Clinical Features

For a diagnosis of autism, characteristic problems in social interaction (autism) are required along with problems in communication and play as well as unusual restricted and repetitive interests. By definition, autism has its onset before age 3 years. Social problems are the central defining feature of autism and are weighted more heavily than other factors. International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) criteria for the disorder are listed in

Table 4.2. The condition was first described by Leo

Kanner in 1943. Kanner noted that the children exhibited an apparently congenital inability to relate to others (autism) and were overly concerned with changes in the nonsocial environment. Hand flapping and other purposeless repetitive movements were common as were unusual aspects of language (when language developed at all). For example, Kanner mentioned that children with autism often repeated words or phrases, had trouble in pronoun use (referring to themselves in the third person), or had highly idiosyncratic language. For some years after his description, there was confusion about whether autism might represent the earliest form of childhood schizophrenia, but by the 1970s, it was clear that autism was a distinct condition. Similarly, there was speculation, particularly in the 1950s that parents might “cause” autism, such as through deviant parenting, but longitudinal data made it clear that autism was a strongly genetic, brain-based disorder.

Autism is an early-onset disorder. Most parents report concerns in the first year of the child’s life, and about 90% are worried by age 2 years. Common concerns include language delay, social deviance, or odd interests in the nonsocial environment (

Table 4.3). Although

Kanner originally believed autism to be congenital but in a minority of cases (∽20%), it appears that the child develops normally or near normally for some months before development slows or actually regresses. This phenomenon has been difficult to study given the reliance on retrospective report, but prospective studies of at-risk populations (e.g., siblings) should help to clarify aspects of this issue.

The social disturbance in autism is very distinctive and is an essential diagnostic feature. It cannot be accounted for simply by associated cognitive problems or intellectual deficiency (see

Chapter 5). Normally developing infants are profoundly social from the first months of life, but those with autism appear to have little interest in the human face or social interaction. Early social problems can include lack of engagement as expressed in a failure to respond to name, failure to engage in joint attention, and reduced babble or vocal play; these problems are the basis for many early screening procedures (

Coonrod & Stone, 2005;

Volkmar & Wiesner, 2009).

Delays in speech are a common presenting problem, and communication problems are a major defining feature of the condition. In the past, about half of individuals with autism had little or no expressive speech; with earlier diagnosis and treatment, that number has decreased. Children who do talk have speech remarkable for echolalia (immediate or delayed repetition of words or phrases), problems with a monotonic voice, idiosyncratic language, pronoun reversal, and major difficulties with the social use of language (pragmatics). These problems are very specific to autism (i.e., they are not like those of children with other kinds of language delay).

Behavioral problems are often striking with a marked contrast between the child’s lack of engagement with the social work (autism) and an overfocusing on aspects of the nonsocial environment (problems with change or preoccupations with sensory experiences). Often, the child is very sensitive to nonspeech sounds but much less responsive to speech. Stereotyped (purposeless and repetitive) movements are common and include hand flapping, toe walking, and so forth, and they may consume much of the child’s time. Unusual affective responses are also common, and play skills are often delayed.

Kanner initially believed children with autism probably had normal cognitive potential because the children often did well with nonverbal tasks (puzzles). The trouble they had with verbal activities was initially “written off” to negativism, but over time, it became clear that children with autism often have areas of cognitive strength and areas of great weakness and that poor performance should not simply be ascribed to lack of motivation. By around age 5 years, IQ scores (even when scattered) become more stable and begin to predict outcome. As with language development, earlier detection and intervention may well be leading to improved cognitive outcomes, presumably by way of minimizing the negative effects of autism on learning. Occasionally, unusual islets of marked ability (e.g., rote memory or block design) may be present. A few persons with “autistic savant skills” exhibit remarkable abilities in drawing, musical ability, or calendar calculation, but these abilities are usually accompanied by major deficits in other areas (see

Hermelin, 2001). Typically, nonverbal skills are stronger than verbal skills. It is fairly common for autism to be associated with overall cognitive skills in the intellectual deficient range, although it appears that with early intervention, this number is decreasing.

Epidemiology and Demography

Many different studies of epidemiology have been conducted. The median rate of autism (strictly defined) is about one per 800 to 1000 people. Rates of autism appear to have increased in recent years, although this change also parallels greater recognition of cases, particularly in more able children as well as changes in diagnostic criteria; the latter were, in part, intended to improve detection in more cognitively able individuals.

There is a male predominance (three to five times more common), although in lower IQ groups, this is much less pronounced, and in high IQ cases much more pronounced. Among individuals with normal cognitive levels, the male predominance may be 25 or more to 1. Although cultural and ethnic issues may impact treatment and, to some extent, case detection, autism generally is remarkably similar around the world. The early impression that autism was more likely in children of parents with more education and higher occupational status proved to be incorrect and probably reflected bias in referral source.

Etiology

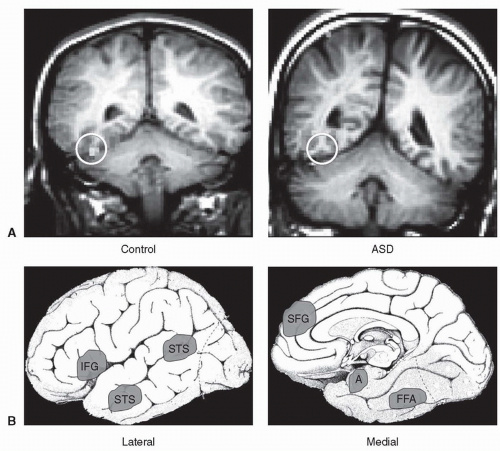

A host of findings support the importance of neurobiology in autism (

Table 4.4 and

Figure 4.1). Individuals with autism exhibit an increased frequency of physical anomalies, persistent primitive reflexes, and various neurologic soft signs, as well as increased abnormalities on electroencephalograms (EEGs). Neurobiological theories have focused on different brain regions related to social information processing. Given that some aspects of functioning are spared, it does it seems likely that some areas must be less affected (e.g., occasionally, a person severely impaired with autism may have unusual musical or drawing ability or remarkable memory skills). Increasingly, sophisticated neuroimaging methods have suggested a possible role for the amygdala (e.g., in social perception and social thinking) as well as in portions of the frontal lobe and areas of the brain involved in social information processing. Overall brain size in autism becomes increased in those with autism in the first years of life, possibly suggesting abnormalities in neural connectivity. Studies using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) have shown underactivation of the fusiform gyrus during facial recognition tasks, an observation consistent with a large literature suggesting important differences in processing of faces and face-like stimuli (

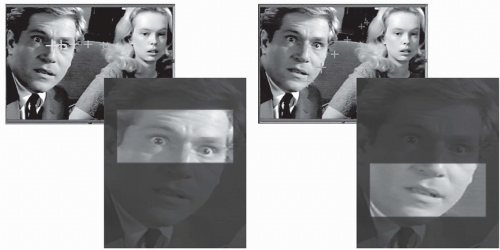

Figure 4.2). Difficulties with social information processing are also suggested by studies of eye tracking in individuals with autism showing that individuals with autism are more preoccupied with less socially salient aspects of scenes and may overfixate on less relevant details. Available postmortem studies have revealed some abnormalities in the limbic system and other areas involved in social cognition. Some animal models (e.g., based on lesion work) have been proposed.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access