▪ Disorders of Communication

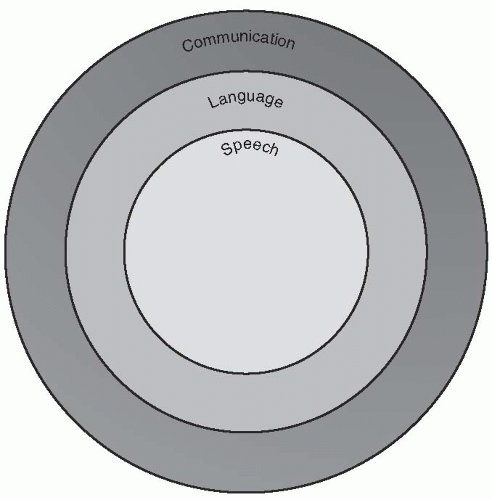

Language is a uniquely human ability and one that is easily disrupted. As a result, disorders of language development are frequently associated with various other conditions, although they can occur in isolation as well. The concept of communication refers to language as well as gestures and body language; speech is an important part of the more general communication domain (Figure 7.1). Although animals can communicate (e.g., with calls signaling danger or warning), only humans truly use language to express ideas, thoughts and feelings. These utterances are often totally new, that is, they are created without being previously heard. Speech is one mode of language; writing provides another form of expression. For individuals who have already learned to communicate and write but then experience impediments to speech (e.g., after a stroke), written communication can be a substitute. The situation is more complicated when difficulties occur in the developmental period before these various forms of communication are established.

BACKGROUND

In the early 19th century, Gall differentiated children experiencing problems with language from those with cognitive-intellectual disability. The investigations of Broca and Wernicke led to important discoveries about the brain localization of language functions as they studied aphasia in adults. Indeed, in the first century of study of language difficulties, neurologists dominated the field, and the focus tended to be adults. This changed as Samuel Orton, a neurologist, began the scientific study of child language disorders. He noted the relevance of these problems to behavior and problems in learning, particularly reading and writing. In the mid 20th century, psychiatrists, psychologists, and pediatricians such as Arnold Gessel began to study what was termed “infantile aphasia.” Benton developed the notion of a specific disorder of language learning in children similar to adult aphasia. In a parallel body of work, educators were struggling with the problem of best teaching methods for children who were deaf or who exhibited severe language problems. Attempts were made to start differentiating various types of children with language-speech problems. Around the same time, interest in child language began to increase, with Chomsky’s work on transformational grammar.

FIGURE 7.1. Domains of communication. Reprinted from Paul, R. (2007). Disorders of communication. In A. Martin and F. Volkmar (Eds), Lewis’s Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: A Comprehensive Textbook, p. 418. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. |

DEFINITIONS AND CLINICAL FEATURES

Communication disorders are broadly defined and impair the individual’s ability to engage in interaction socially. The current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-IV) approach recognizes several different disorders depending on the pattern and nature of the communication problem. It also emphasizes both functional impairment and a judgment of impairment relative to other developmental abilities and certain other conditions.

In expressive language disorder, scores on measures of expressive language must be “substantially” below those for nonverbal cognitive and receptive language ability. These problems must interfere and not be attributable to a mixed receptive-expressive language disorder or an autism spectrum condition. Care should be used in making this diagnosis in the face of intellectual disability, gross deprivation, or sensory-motor deficits. Individuals with this condition usually have limited expressive language with a limited vocabulary.

Key Concepts and Terms

Pragmatics: the social use of language

Syntax: the way words are put together

Semantics: the meaning of language

Phonology: the sounds of language

Morphology: word formation; system of word formation

Case Report: Expressive Language Disorder

Jimmy was an active, sociable 2.5-year-old child whose parents complained to his pediatrician about his language development. His mother had a normal pregnancy, labor, and delivery. His early developmental milestones were within normal limits except that his speech was delayed. He said his first word at around 15 months, but his understanding of language seemed fine. He had experienced two ear infections, but his hearing had recently been tested and was normal. The pediatrician referred him to a speech-language pathologist, who tested him. Jimmy’s receptive vocabulary was above age level. He was able to follow age-appropriate commands, but his expressive vocabulary was significantly delayed and his expressive output limited. His parents were both concerned, and the speech-language pathologist began to work with Jimmy on a regular basis and included his parents in sessions to help them carry over techniques to home. By age 4 years, Jimmy’s expressive language was only slightly delayed, although he had some difficulty in formulating more complex sentences.

Comment: The issue of when to intervene in children with more isolated expressive language delays is somewhat controversial. Many children who are late talkers go on to do well. In this case, the significance of the expressive delay prompted the parents and therapist to begin treatment, with a good result. Some children with this pattern of difficulties may go on to have other problems in school (e.g., with writing). Jimmy’s excellent response to treatment is a good prognostic sign.

In mixed receptive-expressive language disorder, the requirements are the same as for expressive language disorder, but in the mixed type, receptive skills are also substantially below what would be expected given the individual’s nonverbal cognitive abilities.

Thus, in expressive language disorder, the individual’s expressive abilities are below what is expected given the child’s nonverbal cognitive abilities. In contrast, language understanding is relatively preserved. Language may be slower to develop, and articulation problems may be noted as the child learns to speak. In mixed receptive-expressive language disorder, both receptive and expressive skills are below expected levels.

Phonological disorder (also referred to as developmental articulation disorder in the past) is characterized by a failure to produce and use “developmentally expected” speech sounds. These problems, which can include sound substitution, sound omission, and other errors in making sounds, must interfere with communication and academic or occupational achievement. As with expressive and mixed receptive-expressive language disorder, the diagnosis can be made in the presence of intellectual disability, neglect or deprivation, or sensory-motor problems only when they are greater than would otherwise be expected. Children with phonological disorders have delays or an inability to produce certain speech sounds. As a result, they often substitute sounds (W for R) or leave off the final consonant at the end of words. Sound distortions may also be present (i.e., an approximation of the sound is used). Less frequently, additions of sounds may be noted (e.g., “uh uh, give me that”). Some children have other sound production difficulties. Although many children improve with age (with or without treatment), the condition may be a source of distress and, in severe cases, may result in speech that is not intelligible.

Stuttering (previously referred to as stammering) is a condition characterized by disturbance in the flow of language (e.g., repetition of sounds or whole words, word substitutions). This problem must be a source of academic or occupational interference. It is often associated with behavioral difficulties and affective problems. Various speech dysfluencies may be involved, including blocking of sounds, hesitations, and tense pauses. Although many children exhibit

dysfluencies early in life, these usually tend to involve larger linguistic units (words, phrases, and sentences). In contrast, for a child with persistent stuttering, these dysfluencies usually involve repetitions of sounds or syllables (“s-s-s-s-struck’ or “vi-vi-vi-vi-video”). In other cases, sounds may be prolonged (“WWWWWait!”). There can also be blocks when the child is struggling to attempt to make a sound; often this is associated with observable signs such as blinks or grimaces. The prognosis is better if the dysfluencies are relatively effortless and if the child begins to improve within the first year. The International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) diagnostic guidelines make a distinction between stuttering (where there are frequent repetitions or sound prolongation) and cluttering (where there are fluency breakdowns without repetitions or hesitations). There are some other differences as well. These differences between the DSM and ICD approaches reflects a continuing controversy about the nature of stuttering and its relationship (or lack thereof) to other speech disorders.

dysfluencies early in life, these usually tend to involve larger linguistic units (words, phrases, and sentences). In contrast, for a child with persistent stuttering, these dysfluencies usually involve repetitions of sounds or syllables (“s-s-s-s-struck’ or “vi-vi-vi-vi-video”). In other cases, sounds may be prolonged (“WWWWWait!”). There can also be blocks when the child is struggling to attempt to make a sound; often this is associated with observable signs such as blinks or grimaces. The prognosis is better if the dysfluencies are relatively effortless and if the child begins to improve within the first year. The International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) diagnostic guidelines make a distinction between stuttering (where there are frequent repetitions or sound prolongation) and cluttering (where there are fluency breakdowns without repetitions or hesitations). There are some other differences as well. These differences between the DSM and ICD approaches reflects a continuing controversy about the nature of stuttering and its relationship (or lack thereof) to other speech disorders.

Case Report: Mixed Receptive-Expressive Language Disorder

Vinny had been noted to have delays in both his receptive and expressive language as a toddler. His family and primary care doctor adopted a “wait and see” attitude, partly because his father also had delays in language and then developed normally. By the time he was 4 years old and entering preschool, Vinny’s difficulties with language remained striking. An evaluation was obtained. Although his problem-solving abilities were at the average level and he was noted to have strengths in the area of visual learning and problem solving, auditory processing was an area of weakness, and both receptive and expressive language were significantly delayed. A diagnosis of receptive-expressive language disorder was made, and speech therapy was begun. By 6 years of age, Vinny was exhibiting attentional difficulties in first grade, and his continued language difficulties posed further obstacles for his learning. Fortunately, his reading skills turned out to be a relative area of strength for him, and he used this, in part, to compensate for his language problems.

Comment: It is not unusual for children with mixed receptive-language disorder to have other problems, commonly other learning difficulties and attentional problems. Fortunately for this child, reading was an area of relative strength and provided some opportunities for compensatory learning.

Phonological Disorder

Larry was a pleasant but somewhat shy 4.5-year-old child seen for a kindergarten screening. His birth and early development were unremarkable. He had a few ear infections, but his hearing had recently been tested and found to be within normal limits. During the screening, he had shown some articulation errors and was referred to a speech pathologist, who noted difficulties with some of the later-developing consonant sounds (e.g., z, sh, th, r). Sometimes Larry would simply omit these sounds from words or put in other sounds in their place (e.g., w for r). His difficulties became more notable when he had to string together multiple words. His speech was best articulated when he was calm and spoke in a slow, deliberate fashion. Although his parents could understand almost all of his speech, the speech pathologist suggested that likely a classroom teacher and peers might only be able to understand 80% of it. Because of this and what appeared to be his own awareness of the difficulty, speech therapy was begun with a good result. Two years later, he was having only occasional difficulties.

Comment: Often the prognosis is good so that by age 6 years, many children with mild to moderate problems are doing well. Sometimes problems can persist, particularly if speech becomes more complex or rapid.

Case Study: Stuttering

Johnny, a 6-year-old boy, started to stutter around 3 years of age. Both his speech and motor milestones had been slightly delayed. As his language developed, he began to have difficulties with fluency, pausing at certain words. This problem was initially only occasional, but over time, it became frequent, and he began to repeat some sounds and got stuck on the initial sound in the word (e.g., “h-h-h-h-help me out”). There was a strong family history of stuttering. Eventually, intervention was obtained and focused on helping Johnny have better control over the rate of his speech.

Comment: It is common to observe a strong family history of stuttering. Prognostic factors, in addition to family history, include persistence of the difficulty over time, its association with other language problems, and the individual’s or family’s anxiety about the problem.

Although not recognized as an official diagnosis, the term childhood apraxia of speech is sometimes used to describe a subset of cases in which speech difficulties are severe and persistent. In these cases, the range of speech sounds is limited, there are difficulties in sound imitation, the rate of speech is slow, and there are many sound omission errors. This concept was originally thought of as an analogue of adult acquired neurologic disorders of speech. The validity of the concept has been controversial and newer techniques, including neuroimaging, have not supported the comparison to adult disorders. Similarly, in the past, terms such as childhood aphasia and congenital aphasia were used to describe language disorders with a straightforward connection to the acquired aphasias of adulthood.

Several features of the DSM-IV-TR approach to diagnosis should be noted. Interference is emphasized as is the role of formal language and psychological testing. Some degree of clinical judgement is also allowed. Given that communication difficulties are part of the definition of autism and related conditions, certain communication disorders cannot be diagnosed in the presence of autism or pervasive development disorder (PDD). In contrast, the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association defines language disorder somewhat differently as impairment in “comprehension and/or use of a spoken, written, and/or other symbol system.” In this view, the problem could be in language form, content, or function—or combinations of these. Speech disorders refer to problems with sound production and thus are intrinsically more limited. Comprehension can often be intact, but speech fluency can be affected (stuttering) or pronunciation of specific sounds may be affected (phonological disorders).

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND DEMOGRAPHICS

Given differences in definition and method, it is not surprising that estimates of the prevalence of specific language disorders vary widely given different approach to definition. Clearly, language delays are the most common presenting complaint of parents of preschool children; estimates vary, but overall, the median prevalence rate is about 6%, with boys more likely than girls to be impaired. By school age, the prevalence of primary language disorders is about 4% to 7%. One complexity is that there can be overlap with other disorders (e.g., learning

disabilities and dyslexia). Specific language disorders combined with learning disabilities are some of the most prevalent disorders of school-age children. Disorders of language expression are probably more common than those involving comprehension, although even when the problem seems to be primarily expressive, and there are often subtle difficulties in reception as well. The most frequent speech-communication disorders are the phonological disorders, which represent about 80% of referrals to speech clinics. About 5% to 6% of school-age children have articulation problems; in preschool, this number is at least double. The incidence of stuttering is highest between ages 2 and 4 years, affecting as much as 5% of the population.

disabilities and dyslexia). Specific language disorders combined with learning disabilities are some of the most prevalent disorders of school-age children. Disorders of language expression are probably more common than those involving comprehension, although even when the problem seems to be primarily expressive, and there are often subtle difficulties in reception as well. The most frequent speech-communication disorders are the phonological disorders, which represent about 80% of referrals to speech clinics. About 5% to 6% of school-age children have articulation problems; in preschool, this number is at least double. The incidence of stuttering is highest between ages 2 and 4 years, affecting as much as 5% of the population.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree