▪ Intellectual Disability (Mental Retardation)

BACKGROUND

Awareness of children with significant problems in learning and development can be traced to antiquity, although modern interest in what is now termed intellectual disability (ID) began at the time of the Enlightenment and increased greatly during the 19th century. This was a time of great social upheaval. This was also a time during which infant and child mortality began to decline and there was increased interest in children and in their education. Interest in children’s development led to debates about the role of experience (nurture) versus endowment (nature). The interest was exemplified in the report of the French physician Itard who reported on Victor, child thought to be wild or “feral” (but who probably had autism). Specific methods for stimulating children’s development were used, and facilities for caring for children with intellectual deficiency became available. Although initially the impetus was to provide rehabilitation, such facilities often became places for custodial care, a program that has now led to the emphasis on providing services within homes and communities.

The development of the first adequate test of intelligence early in the 20th century also stimulated interest in children with delayed development as it became possible to more precisely characterize levels of disability. In France, Alfred Binet developed the idea of the “mental age” by looking at knowledge that was normatively expectable for children at certain ages. Subsequently, the concept of Intelligence Quotient (IQ, originally produced by dividing mental age by chronological age and multiplying by 100) made it much easier to compare children of different ages and levels of ability. There was considerable faith in the IQ as a valid predictor of subsequent development (i.e., as a fixed measure), and this led to a number of problems and problems. Over time, it became clear that IQ scores did not become particularly stable, in large groups of children, until around the time the child entered school (this is not surprising because IQ tests were originally designed to predict success in school). Studies conducted in the 1930s and 1940s, often on children in orphanages or other institutions, began to show significant effects of experience. In the 1940s and 1950s, there was increased awareness that the IQ score was indeed the product of both experience and endowment, and therapeutic optimism again increased for improving the functioning of children with mental retardation (MR).

It also became apparent that IQ alone was not an adequate predictor of adult self-sufficiency. The focus on appropriate self-care or “adaptive” skills led the psychologist Edgar Doll to develop the Vineland Social Maturity Scale. The current version of this scale continues to

serve as an important tool in the assessment of children with ID. Importantly, in contrast to IQ, adaptive skills can be readily taught.

serve as an important tool in the assessment of children with ID. Importantly, in contrast to IQ, adaptive skills can be readily taught.

Howard Skeels and the Iowa Study

In a classic study, Skeels and Dye demonstrated this practically by transferring infants and young children from an orphanage to a home for the “feeble minded” to make the children “normal.” This fantastic plan had been prompted by clinical observation that children in the home for the feeble minded received considerably more stimulation than those in the orphanage. Skeels later reported major differences in outcomes for these better-cared-for children, both in childhood and in later adult life.

Another body of work centered on the delineation of specific syndromes of ID. For example, Dr. Langdon Down reported on a syndrome (which now bears his name) that we now recognized as being the result of a trisomy of chromosome 21. At the time of his report, Dr. Down, of course, had no notion of chromosomes. Indeed, although his theoretical understanding was fundamentally flawed, Down’s clinical observation has been remarkably robust. As time went on, more syndromes of ID were identified. It became clear that ID could result from a range of risk factors, including problems related to the developing fetus, and ranging from genetic factors (Down syndrome) to exposure to toxins in utero (fetal alcoholism) to maternal infections (congenital rubella). This is an area of active work, and advances in genetics and neurobiology have led to an increasingly detailed understanding of pathophysiological mechanisms.

A series of court cases and legal and social initiatives began to significantly change the care of individuals with ID. Over the past 50 years, there has been an emphasis on caring for children in their homes and communities and avoiding institutionalization. This movement has been further stimulated by the mandate of the U.S. federal government that schools provide appropriate education for all children with disabilities within integrated settings when possible. In the United States, many students with ID are largely or entirely integrated into classrooms with typically developing age mates, although there are marked state-to-state variations, and the benefits of mainstreaming remain debated as students with more severe disabilities may continue to have more restricted experiences. As noted subsequently, the study of mental health aspects of ID has increased substantially during this time, although adequate mental health services often remain difficult to obtain.

DEFINITION AND CLINICAL FEATURES

Intellectual deficiency (ID) (previously referred to as mental retardation) is defined on the basis of (1) subnormal intellectual functioning, (2) commensurate deficits in adaptive functioning, and (3) onset before 18 years. Subnormal intellectual functioning is defined by an IQ lower than 70, usually determined on an appropriate standardized test of intelligence. Deficits in adaptive skills (social and personal sufficiency and independence) are generally measured using instruments such as the recently re-revised Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales. Specific tests of intelligence and adaptive behavior are discussed subsequently. Guidelines for diagnosis are summarized in Table 5.1.

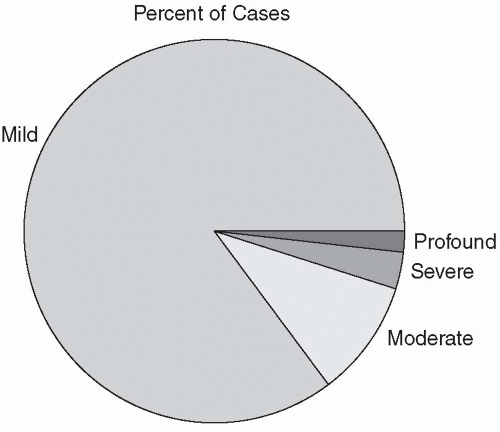

Various levels of ID have been specified: mild (IQ, 50-70), moderate (IQ, 35-49), severe (IQ, 20-34), and profound (IQ <20) (Figure 5.1). Unspecified ID can also be noted if, as sometimes happens in very disabled individuals, it is not possible to administer usual tests of intelligence. Borderline ID can be noted as a V code in DSM-IV. Some flexibility is allowed for clinical judgment. Most persons with ID in childhood are those with mild ID (∽85% of

cases); the remainder of cases include those with moderate (∽10%), severe (about 4%), and profound (1%-2%) ID.

cases); the remainder of cases include those with moderate (∽10%), severe (about 4%), and profound (1%-2%) ID.

TABLE 5.1 DIAGNOSTIC FEATURES OF INTELLECTUAL DISABILITY AND MENTAL RETARDATION | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

In the past, the distinction was made between educable (IQ, 50-70) and trainable (IQ <50). Although no longer commonly used, this distinction continues to be relevant. For example, persons with mild ID often have psychiatric difficulties that are fundamentally similar (if generally more frequent) to those seen in the general population; this is not true for more severely impaired persons. Similarly, whereas specific medical conditions associated with ID are more likely in the group with an IQ lower than 50, lower socioeconomic status is more frequent in the group with mild ID. The proportion of persons with severe and profound ID is higher than would be expected given the normal curve, reflecting the impact of genetic disorders and severe medical problems on development. By definition, the disorder has its onset in childhood or adolescence (e.g., a young adult who sustained a brain injury and subsequent IQ deficits would not receive a diagnosis of MR).

The clinical presentation varies depending on a host of factors, particularly the level of ID. Thus, children with severe and profound ID come to diagnosis earlier, are more likely to exhibit dysmorphic features and associated medical conditions, and have higher rates of behavioral and psychiatric disturbances. The latter can be quite different from those seen in the general population (e.g., self-injurious behaviors, unusual mood problems). Although individuals with mild ID have increased rates of psychopathology (compared with the general population), the nature of problems seen is fundamentally similar to those in normative samples. Persons with moderate levels of ID are intermediate between these two extremes.

Somewhat paradoxically, for many years, the diagnosis of ID tended to cause clinicians and researchers to overlook the presence of associated psychiatric and behavioral problems, a phenomenon known as “diagnostic overshadowing.” As researchers began to look, it became clear

that individuals with mild ID exhibited a four- to fivefold increase in mental health problems. In general, at least 25% of persons with ID may have significant psychiatric problems; these rates are much higher if persons with salient behavior problems are included. Although issues of diagnosis and assessment can be complex, it appears that rate of schizophrenia, depression, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder are all increased relative to the general population. Various rating scales and checklists specific to psychiatric problems in this population have been developed (see Bouras and Holt, 2007, for a detailed discussion). Modifications of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-IV) criteria for persons with ID have also been developed (Fletcher, Loschen, Stavrakaki, & First, 2007).

that individuals with mild ID exhibited a four- to fivefold increase in mental health problems. In general, at least 25% of persons with ID may have significant psychiatric problems; these rates are much higher if persons with salient behavior problems are included. Although issues of diagnosis and assessment can be complex, it appears that rate of schizophrenia, depression, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder are all increased relative to the general population. Various rating scales and checklists specific to psychiatric problems in this population have been developed (see Bouras and Holt, 2007, for a detailed discussion). Modifications of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-IV) criteria for persons with ID have also been developed (Fletcher, Loschen, Stavrakaki, & First, 2007).

Case Report: Mild Intellectual Deficiency

Jimmy was born at term after an uncomplicated pregnancy, labor, and delivery. His early developmental milestones were slightly delayed. Jimmy did not walk until 15 months and did not use words until he was nearly 2 years of age. His parents expressed concern to their pediatrician, and Jimmy was seen for assessment when he was 3.5 years old. At that time, developmental testing suggested borderline cognitive ability with a fairly even profile. His strengths included his social engagement and motivation to please. Various medical evaluations were undertaken, and results were uniformly negative. There was no family history of ID nor did Jimmy exhibit any unusual physical findings or features. Genetic consultation was noncontributory. He was enrolled in a program in which he had special supports as well as opportunities for interaction with typically developing peers. By age 8 years, repeat psychological testing revealed a full-scale IQ of 68 with some areas of weakness and strength becoming more pronounced. Jimmy continued to receive some special help with classes and had a modified curriculum. Starting in adolescence, he began a part-time job working in a local restaurant, where he was well liked and popular. More and more of his work in school focused on vocational issues. He had some difficulties with depression and anxiety as a young adult but now lives largely independently from his parents, who see him on a regular basis. He has an active social life and continues to enjoy his job.

Comment: Often, the diagnosis of mild ID is not made until the child is nearing entry to school or preschool. Individuals with mild ID often are able to achieve considerable independence and personal self-sufficiency, particularly when, as in this case, efforts are made to encourage community and vocational skills.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND DEMOGRAPHICS

The use of both subnormal intellectual functioning and deficits in adaptive behavior in the definition of ID has important implications for epidemiology. If only the IQ criterion is used, the expectation, based on the normal curve, would be that 2.3% of the population should exhibit ID. However, this number is significantly decreased, particularly in adulthood, if the adaptive criterion is included. Figure 5.2 summarizes these differences in approach as exemplified in two different studies.

The prevalence ranges from three or four cases per 1000 for severe MR with rates from five to 10 children per 1000 for mild MR. The frequency is increased in boys over girls. Not surprisingly, times of case detection vary depending on several factors, including level of disability. Thus, profound or severe MR is likely to be recognized early in life, but mild ID is frequently not recognized until the school years. Rates of mild ID are increased in individuals at great environmental risk (e.g., because of poverty or lower socioeconomic status). Identifiable medical syndromes become more frequently observed below an IQ of 50. As noted, the age of diagnosis often varies depending on the severity of the disability, so persons with more severe ID present for clinical assessment earlier than those with mild, or borderline, intellectual deficiency. The advent of more precise methods for genetic testing has shown, in some cases, that some individuals with specific genetic syndromes function in the mild or even borderline range.

Case Report: Severe Intellectual Deficiency

Jeff was born after a term pregnancy and uncomplicated labor and delivery. He had nursing problems. His early milestones were delayed, and he had recurrent ear infections. Referral for genetics consultation was made at age 2 years because of delays and the pediatrician’s concern about his unusual appearance. Jeff had a short and wide head (bradycephaly), a flattened midface, and low-set ears. He also had short but broad hands. On developmental testing, he was significantly delayed in all areas. A diagnosis of Smith-Magenis syndrome (a deletion at 17p11.2) was made by testing and was consistent with the clinical picture. Jeff enjoyed being around adults and exhibited considerable attention-seeking behavior. When frustrated, he began to engage in head banging, although this decreased as he became older. Jeff had limited communication skills, and his frustration around communication issues seemed to exacerbate his behavioral problems. Jeff also had significant sleep problems.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree