▪ Learning Disabilities and Developmental Coordination Disorder

LEARNING DISABILITIES

Interest in what now are termed the learning disabilities began in the 19th century with the increased emphasis on universal public education and with an awareness of adults with major problems in reading. The term dyslexia was used to describe the problem, and many different terms have subsequently been used. A strong link to language difficulties (aphasia) was assumed, and this was further emphasized in the 1920s by the neurologist Orton, who speculated that left hemisphere damage (to the language centers) was involved. The topic of definition and issues of broader conceptualization of learning problems remains an area of active debate and discussion. Samuel Kirk proposed the term learning disabled in 1963, and the concept promptly gained acceptance from parents who established the Association for Children with Learning Disabilities. As a practical matter, changes in U.S. federal law, in the late 1960s, began to use the term for children whose ability in some specific area, often reading or math, falls below that which might be expected given their skills in other areas.

Public Law 94-142 (the Education for All Handicapped Children Act) became law in 1975 and established the right of children to a free and appropriate education. This law, now amended several times, has been critical in helping children with disabilities obtain educational services. Before its passage, perhaps only 20% of children with disabilities received educational services in public school. At that time, schools provided education to only one in five children with disabilities, but by 2003 to 2004, more than 6.5 million children were serviced under this program. Children with specific learning disabilities make up 50% of all special education students served under this program.

Given the strong relationship to school and academic performance, these problems are, essentially, confined to school-aged children and adolescents but can persist into adulthood.

Additional difficulties arise because in addition to legal definitions (which themselves change over time), somewhat different approaches have been taken by the many different specialties dealing with these problems. Under current law, a child who exhibits a learning disability can qualify for special help and services in school, and an entire system for developing an Individualized Education Program (IEP) is implemented when it is clear after an assessment that the child qualifies for services.

Definition and Clinical Features

In 1980, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual III (DSM-III) included a concept termed academic skills disorder Over time, this concept has evolved in both the DSM and International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) to encompass several different disorders. Both the DSM-IV-TR and ICD-10 use an approach, now seen as somewhat outdated, in the learning disabilities field of basing diagnosis on a discrepancy model (i.e., in which the child’s performance on an achievement test is significantly lower than IQ). In the DSM-IV-TR, a learning disorder is diagnosed “… when the individual’s achievement on individually administered, standardized tests in reading, mathematics, or written expression is substantially below that expected for age, schooling, and level of intelligence.” As a practical matter, this method is overly stringent and excludes many children who might profit from intervention. The current DSM-IV-TR approach recognizes three explicitly defined categories: Reading Disorder, Mathematics Disorders, and Disorder of Written Expression. A residual category (learning disorder not otherwise specified [NOS]) is also provided. These terms are generally equivalent, overall, to the term for learning disability (LD) recognized in federal regulations.

The DSM-IV-TR approach, now more than 15 years old, was based on then (1994) current methods that relied on discrepancy scores (e.g., of reading difficulties significantly below the level expected by overall cognitive ability). The ICD-10 approach to definition of these conditions is rather similar but includes an explicit requirement that the school environment is one that is appropriate to the child’s ability to learn the skill. As defined in DSM-IV-TR, each of the conditions is characterized by achievement that is “substantially below” expectable levels given age, IQ, and educational level. By definition, the problem must be interfering in some way. Sensory deficits can be present, although the additional learning difficulty is diagnosed only when the achievement delays are even greater than would be expected.

Changes in definition in terms of eligibility for services have come from several sources. In the 2004 amendment to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), a series of 13 categories were recognized, including specific learning disability. The notion of “specific” learning disabilities is used to emphasize the difference between these conditions and more general learning problems (e.g., intellectual deficiency). A specific learning difficulty should not be diagnosed if other factors (e.g. lack of exposure, language, or cultural issues) better account for the problem. An awareness of the potential problems led to then introduction of a new concept, Response to Intervention (RTI),in the 2004 amendment of IDEA

Other learning disorders of potential interest such as the nonverbal learning disabilities profile (Rourke et al., 2002), are not officially recognized. This diagnostic concept is of some interest given its rather different pattern of presentation and unique constellation of neuropsychological findings (strengths in verbal areas and weaknesses in nonverbal areas but with significant developmental shifts over time as children learn to use their strengths to compensate for their weaknesses). It is likely that substantial revisions in the learning disabilities category will occur in DSM-V.

Typically, children present with learning disabilities as they enter school environments and their progress in some specific area lags behind that in other areas. Recognition of learning difficulties and differences can be delayed in some circumstances (e.g., children who have higher cognitive abilities may present with problems sooner than those with lower abilities). Similarly, children whose problems are mild and associated with other conditions (see below) may have learning difficulties that are recognized only over time.

Epidemiology and Demographics

Reading problems are very common in childhood and account for the majority (75%-80%) of learning disorders. Mathematics learning difficulties and disorder of written expression are much less frequent. In math disorder, girls predominate, but in the other two conditions, boys are more likely to have the condition. Disorder of written expression is frequently associated with reading problems and, to some extent, math problems. As noted subsequently, the developmental learning disorders are also strongly related to other conditions, notably attentional difficulties.

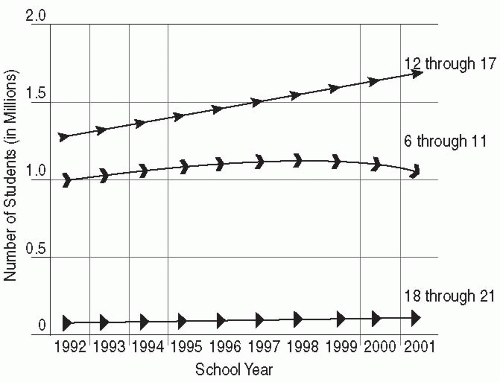

FIGURE 6.1. Recent dynamics of estimates for prevalence rates of learning disabilities in different age groups. (U.S. Department of Education, 25th Annual Report to Congress, 2003. Reprinted from Grigorenko, E. L. (2007). Learning disabilities, p. 412. In A. Martin & F. Volkmar (Eds.). Lewis’s Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: A Comprehensive Textbook. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.) |

Figure 6.1 provides data on the prevalence of learning disabilities data by age group based on data provided to the U.S. Department of Education and then reported to congress. On balance, about 5% to 6% of the total school-age population has a learning disability of some kind. It is the case, however, that rates can vary dramatically from state to state and school district to school district. These differences reflect many different factors ranging from factors that increase the risk of learning disability in the first place (e.g., poverty, lack of exposure to written materials, poor educational programs) to more methodologic issues (failure to detect milder cases given a lack of resources). This diversity in rates also reflects the substantial differences in how local educational programs diagnose learning problems. The discrepancy approach, currently used in DSM-IV-TR, may lead to overdiagnosis of learning problems.

Etiology

Genetic and neurobiologic factors as well as experience play a role in the pathogenesis of learning difficulties. A large body of work has now underscored the importance of genetic factors in these conditions. These factors are presumed to act through one or more brain mechanisms to impact the neuropsychological processes that underlie reading, writing, and mathematics learning (Shaywitz & Shaywitz, 2005). Similarly, experience factors in terms of deprivation and lack of exposure to materials and opportunities to develop basic skills also contribute. Other factors may lead to learning disabilities (e.g., head trauma; treatment of childhood cancers, including central nervous system radiation). Most of the work on etiology has centered on specific reading disability. Various methods have been used to study the neurobiological correlates of reading problems (see Grigorenko, 2007, and Shaywitz & Shaywitz, 2005 for reviews).

Reading skills appear to involve a large network of brain areas, predominately in the left hemisphere of the brain (Figure 6.2), and involve brain regions involved in visual and auditory skills as well as more basic conceptual processing. The four areas that appear to be of greatest relevance to reading include the fusiform gyrus (Broadman area [BA] 37), a portion of the middle temporal gyrus (including part of BA 21 and portions of areas 21 and 37 along with

the angular gyrus [BA 39] and the posterior aspect of the superior temporal gyrus [BA 22]). Differences in brain activation have strong developmental correlates, and more able readers seem to shift to frontal regions, but those with difficulty tend to use most posterior ones (in the parietal and occipital regions) (see Gabrieli, 2009).

the angular gyrus [BA 39] and the posterior aspect of the superior temporal gyrus [BA 22]). Differences in brain activation have strong developmental correlates, and more able readers seem to shift to frontal regions, but those with difficulty tend to use most posterior ones (in the parietal and occipital regions) (see Gabrieli, 2009).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree