Development occurs throughout the life cycle, and although we frequently focus on some particular aspect of development (cognitive, motor, and so on), in reality, developmental processes are fundamentally interrelated. The term

maturation is often used to describe the sequential pattern of growth, but both experience (nurture) and endowment (nature) interact in complex ways. As described in

Chapter 1, various approaches, methods, and theories have been used to understand development. For many investigators, the development of embryos and fetuses has served as a model for subsequent development with the various processes interacting reciprocally. One of the observations consistent with this view is the awareness that early development of motor skills moves in top-down (cephalocaudal or head to tail) and center-out (proximodistal) fashion so that, for example, head control is achieved before trunk control and before leg control, and arm control is achieved before hand control.

Clearly, although the human genome both gives considerable developmental potential, it also sets certain limits. Depending on the particular skill being studied, the relative dominance of genetic or experiential factors may shift so that even if a baby has good genetic potential, his or her placement in a severely depriving environment will result in developmental delays. Conversely, a child born having experienced the effects of some insult in utero such as fetal alcohol exposure may not be able to achieve normative levels of functioning no matter what environment is provided, although even here, optimal development would be more likely in a supportive environment. It is appropriate to begin any consideration of development with a discussion of development before birth.

PRENATAL DEVELOPMENT

Development starts at conception as the zygote begins to develop actively when the egg is fertilized. Within a few days, it will have reached the uterus and implanted and may be 0.1 inches in length. With 2 weeks, the menstrual period may be missed and may alert the mother to the pregnancy. Over the next 6 weeks, major organs and structures develop primarily following the cephalocaudal and proximodistal pattern. By about 8 weeks, the embryo is recognizably human. After this time, the fetus grows rapidly with increased differentiation. The head initially grows more actively than other parts of the body and gradually slows during fetal life so that at birth, the head is about one-fourth the length of the entire body, but in adulthood, it is only

about one-sixth. Conversely, at birth, the legs are about one-third of body length, but this increases to half by adulthood.

By about the third month in utero, fetuses can swallow, make a fist, and wiggle his or her toes. By the fourth month, fetuses can respond to light, and by the fifth month, loud sounds may elicit movement. Similarly, more organized behaviors, such as the sucking reflex, develop before birth; this is also a time when processes such as breathing, body temperature regulation, and swallowing are sufficiently organized to make life possible outside the uterus (problems that must be dealt with in supporting very early premature infants). By around 8 months, fetal fat stores accumulate rapidly. Antibodies from the mother help prevent infection postpartum.

Even before the child is born, the parents begin to experience the child and are impacted by him or her. This happens in various ways. For the mother, the experience of fetal movement (“quickening”) provokes a series of responses as mother observes that the child may be soothed by her speech or movement. Similarly, the mother’s impact on the child begins as soon as fertilization has occurred. Although intrauterine life is relatively homeostatic, it can be influenced by the mother’s health (both physical and psychological) as well as by other factors. Mothers typically gain 25 to 30 lb, and this weight gain is important for fetal growth. Mothers who fail to gain appropriate weight or who are undernourished may increase the likelihood that their baby will be small. Other factors that may adversely impact the development of the child in utero include exposure to radiation, maternal infection, and exposure to drugs.

The effects of teratogens depend on several factors. These include the timing of the exposure (e.g., in some cases, these may even antedate the pregnancy). The first weeks after conception are particularly sensitive as this is a time major organs form; subsequent exposure may impact growth in utero. The dose also is important depending on the agent, with effects ranging from minimal to maximal. The route of the teratogen may also be important. The effects of teratogens can be more generalized or more specific (e.g., thalidomide exposure is associated with limb defects, and alcohol exposure in utero produces a range of problems).

The adverse effects of alcohol on developing fetuses have been recognized since ancient times. Although reports on potential adverse effects on fetuses began to appear in the medical literature in the 1700s, Jones and Smith in 1973 brought new attention to the significant teratogenic effects of alcohol exposure in utero. Fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) is associated with growth deficiency, usually mild intellectual deficiency, a characteristic “flattened” face, motor problems, and other morphologic features. A number of learning difficulties are noted as are language difficulties and continued growth problems. In the United States, alcohol continues to be the most frequently used teratogens and is one of the more common causes of intellectual deficiency. The current recommendation is to avoid alcohol entirely during pregnancy. Chronic alcohol abuse is associated with greater risk, and unfortunately, these are also mothers who are likely to smoke, giving even greater risk to the developing fetus.

A wide range of other common agent have potential deleterious effects. Maternal smoking, for example, clearly impacts birth weight, early delivery, increases rates of placenta previa, and placental abruption as well as still birth. Cigarette smoking contributes to low birth weight and increased risk for sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). Stopping smoking at any point in the pregnancy is beneficial but is particularly so in the first trimester. Similarly, the potentially adverse role of prescription and street drugs has been recognized. The effects of these agents vary. Phenytoin is associated with increased risk for heart defects, and tetracycline can cause staining of teeth and interfere with bone growth. Similarly, streptomycin can be associated with hearing loss, and DES can cause genital abnormalities as well as vaginal and cervical cancer in adolescent girls. Use of many of the commonly available street drugs such as cocaine and crack is associated with increased newborn irritability and sometimes with growth retardation. Agents such as heroin and methadone can result in a withdrawal syndrome in the infant and an increased risk for sudden death.

Maternal Infections can be associated with various adverse effects. Congenital rubella can lead to severe mental retardation, visual and sensory problems, and cardiac difficulties. AIDS is associated with a number of congenital malformations, although fortunately, work on prevention has advanced dramatically in the more developed countries. Similarly, cytomegalovirus

and toxoplasmosis may be associated with significant learning difficulties, intellectual deficiency, and a range of other problems.

Heavy metals and other environmental toxins can be have teratogenic effects as can exposure to radiation. Other risks arise with increased both very young (teenage) or comparatively older (>35 years) maternal age. For older mothers, the risk for Down syndrome begin to increase substantially. Similarly, malnutrition in the mother can be faced with growth retardation and behavioral difficulties in the newborn. Other maternal health issues (e.g., diabetes) can be associated with risk.

Perinatal Variables

Prematurity is an important risk factor for subsequent developmental problems. Premature infants also present challenges for parenting and are more likely to be abused or neglected. Preterm babies (born before the 37th week of pregnancy) or babies with low birth weight (born at or near term but who are small for gestational age) both have increased risk. Although babies born as early as 24 weeks now survive, the lack of development of important organ systems, particularly the respiratory system, presents major challenges. Although we made strides have been made in supporting preterm infants, prevention continues to be a significant public health challenge.

Premature preterm infants are at increased risk for various problems, including neurologic problems, retinopathy, and developmental disabilities. Cardiovascular and respiratory problems are also common. Risks increase with the degree of prematurity. Even when babies are born on time as many as 3% of all infants exhibit significant malformations or birth defects, and another 7% or so may exhibit less serious problems. Babies born with severe developmental difficulties often have difficulties that started even before labor and delivery, although sometimes a traumatic birth can result in major neurologic damage.

Parents of premature babies and babies with birth defects are associated with significant challenges. All parents worry about their babies before birth, but the experience of having a baby with a problem can bring up a host of unpleasant feelings, including anger, anxiety, and even revulsion (if the child has an obvious facial disfigurement as in cleft palate). The sense of loss of the anticipated perfect baby can be a shock and a source of depression. The child’s continued presence serves as a constant reminder of the loss of the idealized infant.

The reactions of the parents are a function of their own histories and personality as well as the visibility and location of the birth defect. For example, hypospadias may require multiple surgical correction and impact the parents’ feelings and attitudes toward the child’s gender. Cleft palate is highly visible and may complicate feeding of the infant, but fortunately, it is usually quite correctable. Congenital heart problems may be noted at birth or sometime later and range considerably in severity. Congenital sensory impairments present special problems. Infants with congenital blindness can show unusual motor mannerisms and have delays in development. Sometimes the parental response is one that tends to isolate the baby—at a time when even more sensory stimulation is called for. On the other hand, visually impaired babies will begin to smile at the sound of the parent’s voice and, with support, can do very well. Although often congenital blindness is thought of as a greater disability, congenital deafness is actually more frequently associated with developmental disturbance and psychiatric problems, presumably reflecting the central importance of language in human development. Intellectual disability is usually diagnosed in infants only when an obvious syndromal condition is present or when the degree of delay is likely to be severe or profound. This condition presents special challenges for parents who must cope with accepting a severely delayed child, their own feelings about the loss of the desired baby, and often associated medical problems.

Responses of Parents and Family of the Newborn

Various factors shape the parents’ attitude towards the fetus and neonate. The first is their relationships with their own parents. There are several views of the ways pregnancy is experienced;

these range from the idea that pregnancy is inherently a crisis to the other extreme, which views pregnancy as a normal part of development. With advances in technology, mothers (and often fathers) are aware of the pregnancy at a very early stage. Often, the first picture of the fetus during ultrasonography concretizes this knowledge. The mother may find herself increasingly preoccupied with herself and then, with the detection of movement in the fetus, she has an independent physical confirmation of the person within her. Although the process goes well for most mothers, sometimes the process is associated with feelings of ambivalence that can precede depression.

Fathers sometime experience some of the symptoms of pregnancy along with their partners (in some culture, fathers may experience feelings at the time of childbirth, couvade). Some fathers will sense, and resent, the preoccupation of the mother with the pregnancy. As with mothers, the father’s experience of being parented can play a major role, although even fathers who have had difficult parental experiences can be loving and affectionate. Sometimes a prospective father becomes more anxious because of a sense of greater responsibility or unresolved issues with his own father. Sometimes the couple’s expectations of each other are changed by the pregnancy. Having a warm and supportive father-child relationship is a clear advantage for the child.

In addition to the parents, other members of the family also play important roles. Around the world, probably the bulk of childrearing (apart from breastfeeding) is done by other children, usually siblings. In developed countries, grandparents, aunts, and uncles often play major roles. Parents may find this helpful or intrusive. Preparation of a sibling for the arrival of a new brother or sister varies depending on the child’s age. Significant siblings conflict or sibling rivalry is more likely in the context of a problematic parent-child relationship, particularly as the mother’s attendance to the older child decreases.

INFANCY AND TODDLERHOOD

In the first weeks after birth, infants quickly become active in learning about the world. They begin to explore the environment through multiple modalities, can track moving objects, screen out invariant stimuli, and become active players in the “social game.” For a typically developing infant, the face or voice of the parent is the most engaging thing in the environment, and this early social interest sets the stage for many subsequent skills in multiple areas.

Tables 2.1 and

2.2 summarize some of the landmarks of development in the first year of life.

After about 1 month of age, infants’ ability to engage in voluntary motor movement begins to increase. Infants also begin to produce more sounds and become increasingly differentiated in their affective responses. Between two and 7 months, there is increased social interaction along with an increased awareness of the nonsocial world and greater coordination of sensation and motor action. By about 4 months, imitation becomes more striking (and further consolidates social interest and attachment). Shortly thereafter, the earliest aspects of object permanence are seen so that things exist to the baby even when not visible; at around this time, infants’ awareness of cause-and-effect relationships also increases (see

Chapter 1 for a discussion of Piaget’s model of cognitive development in infancy). Both discoveries are important building blocks in social-cognitive development (i.e., as infants appreciate their own ability to impact the world and the stability of people in that world). Object permanence is an important foundation for symbolic thinking and language development, and the appreciation of cause and effect helps infants gain a new appreciation of intentionality. Socially, these skills are reflected in games such as peek-a-boo.

Between 7 and 9 months of age, infants develop an awareness that they can be understood by others (i.e., that their mothers or fathers can understand their feelings, wishes, and desires, a phenomenon termed intersubjectivity). Infants’ behavior also becomes more goal directed. Around this time, infants develop more sophisticated strategies for obtaining desired ends by grouping behaviors together in a sequence. These phenomena also serve as a basis for communicative gesturing (e.g., pointing at or reaching for an object while looking at the mother or father to request help in getting it). Advances in object permanence and in social skills development also help infants develop a strong sense of attachment to their caregivers. This is expressed in various ways, including phenomena such as separation anxiety (often starting between 6 to 8 months and peaking sometime after the first birthday) and in the related phenomenon of stranger anxiety (often beginning around 8 months and peaking around age 2 years). Both phenomena speak to infants’ strong awareness of essential caregivers and the ability to differentiate them from strangers.

Several new milestones are usually achieved by, or shortly after, the first birthday and mark major changes in the life of the infant and family. Motor and motor coordination skills advance (

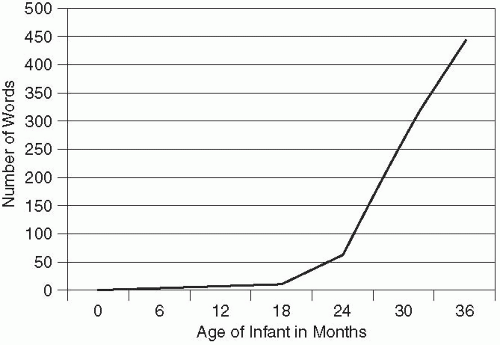

Table 2.1) so that typically by about 12 months, infants begin to be able to walk independently. Similarly, with the onset of language (usually also around this time) and greater symbolic capacities, infants are able to hold multiple bits of information in mind and to appreciate new ways to solve problems using trial and error. Important foundations for language are well established by age 1 year and include the ability to engage in reciprocal interaction, differentiated babbling, and use of sounds and intonation (prosody) typical of their native tongue. When language acquisition starts, knowledge of words usually dramatically increases (

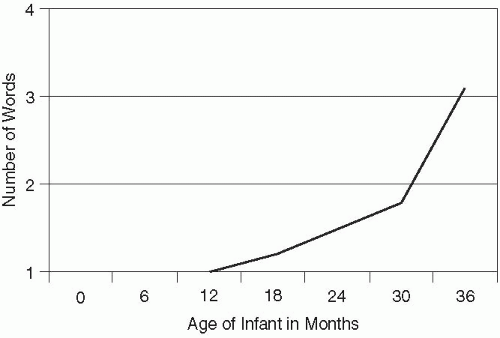

Figure 2.1). Usually by age 2 years, toddlers’ expressive vocabulary is between 50 and 75 words and increases over the next several months so that by age 3 years, is between 500 and 100 words. By this age, typical toddlers also use sentences of three to four words (

Figure 2.2). Increased ability to use language and think symbolically gives the potential for advance planning rather than trial and error.

The increased ability to use symbols also makes for a major reorganization of cognitive development after age 18 months. Increased cognitive abilities are also reflected in phenomena such as deferred (i.e., remembered) imitation. Infants begin to use symbols in play, and play begins to shift from simple functional use of materials to more abstract levels.

Various problems can negatively impact normative development. These are summarized in

Table 2.3 and include problems in self-regulation (eating, sleeping, impulse control, aggression, and mood or anxiety difficulties). Given the centrality of social factors in early development, disturbances in relatedness are particularly important; these can arise as a result of environmental stress, deprivation, or with disorders such as autism. Maternal or parental deprivation can arise because of problems in the parent or life circumstance. Risks arise because of repeated changes in the primary caregiver as well as because of abuse and neglect (see

Chapter 20). In some respects, the intersection of mental health and physical problems can be seen most dramatically at this age, and disentangling cause-and-effect and relationship or individual issues can be difficult. These can take the form of eating problems (see

Chapter 14).

Developmental delays can occur in isolation or across multiple areas. Problems in some areas (e.g., language) may be reflected in other areas as well. Risk is increased by factors such as prematurity and parental substance abuse or nonavailability. Various models of early intervention have been developed and can be helpful. Typically, mild cognitive delays are not noted until later, but more severe delays, often associated with specific genetic and metabolic

disorders, can be seen in infants. These include conditions such as Down syndrome, fragile X syndrome, and Prader-Willi syndrome.