▪ Tic Disorders

BACKGROUND

Tics are sudden, repetitive movements that typically are brief but occur in bouts. They may be quite mild or very severe. They can take the form of gestures or vocalizations. The can be very simple movements (e.g., eye blinking) or much more complex. They can include self-injurious behaviors or take the form of obscene movements (copropraxia). Vocal tics, when present, can range from barely audible throat clearing to the sometimes explosive expression of obscene words or phrases (coprolalia). Vocal tics can involve repetition of one’s own words (palilalia) or the words of others (echolalia). The individual may be able to suppress the tics temporarily and may sense the tic before it happens—a “premonitory urge.” The person may also have some sense of relief after the tic.

In addition to varying in severity, these disorders are often associated with other problems (e.g., in attention and overactivity). These conditions have traditionally been treated by both neurologists and psychiatrists; this reflects the somewhat unique way in which these conditions seem to be at the interface of “mind and body.”

Tics have been observed for hundreds of years and were once viewed as examples of demonic possession. The modern study of tics began in France with the work of Itard and Gilles de la Tourette. It was Tourette who noted the co-occurrence of motor and vocal tics, the association with obsessive-compulsive features, and the strong genetic component to tics.

DEFINITIONS AND CLINICAL DESCRIPTIONS

Several types of tic disorder are presently recognized. The distinctions among these types have to do with the persistence of tics (chronic or transient) and whether vocal as well as motor tics are observed (both are seen in Tourette’s disorder). A diagnosis of tic disorder is not made if the tics are caused by central nervous system disease (e.g., postviral encephalopathies) or psychoactive medication or substance use or abuse.

In transient tic disorder, one or more tics occur (off and on) for weeks to months. These tics are usually motor tics and typically are confined to the head, neck, and upper body. The onset typically is between ages 3 and 10 years, and the diagnosis is frequently missed or unrecognized. In some cases, tics go on to become chronic. Features of transient tic disorder are provided in Table 13.1.

In chronic vocal or motor tic disorder, the tics (either vocal or motor but not both) have lasted for at least 1 year without a long symptom-free period (arbitrarily set at 3 months).

The tics wax and wane over time and can be simple or more complex with a broad range of severity. Motor tics are more common than vocal tics and usually involve the head and upper body. As with other tic disorders, the tics can be voluntarily suppressed for period of time and are exacerbated by stress. The condition may persist into adulthood and become noticeable at times when the individual is fatigued or anxious. Table 13.1 reviews diagnostic features of chronic tic disorder.

The tics wax and wane over time and can be simple or more complex with a broad range of severity. Motor tics are more common than vocal tics and usually involve the head and upper body. As with other tic disorders, the tics can be voluntarily suppressed for period of time and are exacerbated by stress. The condition may persist into adulthood and become noticeable at times when the individual is fatigued or anxious. Table 13.1 reviews diagnostic features of chronic tic disorder.

Did Samuel Johnson Have Tourette’s Disorder?

Dr. Samuel Johnson, the most famous writer in 18th century England and subject of one of the greatest biographies in the English language, may have had Tourette’s disorder. His biographers have noted that throughout his life, Dr. Johnson exhibited various unusual movements and gestures as well as many verbal “eccentricities.” Dr. Johnson had many different symptoms, including bouts of melancholy (depression) as well as some obsessions (e.g., with his feelings of guilt and lack of faithfulness). In his biography of Johnson Boswell noted his “convulsive cramps” and unusual gestures as well as his tendency to talk to himself. His contemporaries commented that his unusual gestures were so extraordinary that he attracted the attention of spectators who would come to watch him. Throughout his life, Dr. Johnson feared that he might become insane, but his contemporaries regarded his difficulties as reflecting some medical illness (e.g., such as a form of seizure disorder).

TABLE 13.1 DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSTIC FEATURES: TIC DISORDERS1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

If both motor and vocal tics are present, a diagnosis of Tourette’s disorder is made. Tourette’s disorder is the best known of the tic disorders. In Tourette’s disorder, both vocal and motor tics must be present. Table 13.1 summaries distinctions among these various categories of tic disorders.

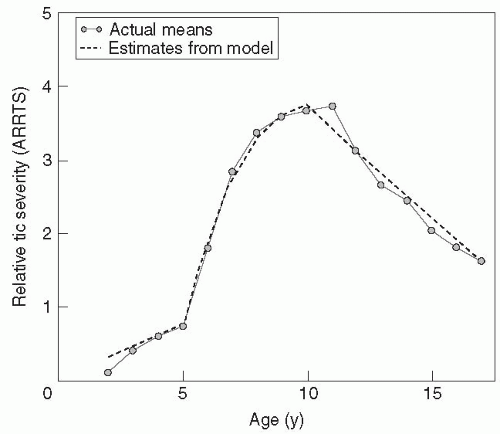

Of these conditions, Tourette’s disorder is the best known and most frequently studied. It usually has its onset in childhood with simple motor tics, often involving the head or face (e.g., eye blinking or head jerks). Gradually, tics come to involve other regions of the body, often following a “rostral to caudal” progression (i.e., head to rest of body). As motor tics persist, they may have a negative impact on the child’s functioning. Typically, vocal or phonic tics usually begin after the motor tics but then have a progression from more simple manifestations (throat clearing) to much more complex forms such as echolalia and coprolalia in a minority of cases. The severity of symptoms tends to a peak in middle childhood (Figure 13.1). As noted subsequently, various other disorders may coexist with Tourette’s disorder and may, in some ways, pose even greater obstacles for treatment.

Transient tics are frequent in childhood but often are of brief duration. On the other hand, sometimes the onset of motor tics marks the onset of Tourette’s disorder often between ages 5 and 7 years. In this condition, motor tics persist and generally progress down and away from the midline (e.g., head, neck, arms, and last and least frequently, the lower extremities). Phonic tics usually appear some time after motor tics (between ages 8 and 15 years) and are rare in isolation. Tic complexity changes with age, although most individuals with Tourette’s disorder have a diagnosis in childhood. It is important to note that the severity of tics in Tourette’s disorder waxes and wanes over time. Tics can be voluntarily suppressed for brief periods and are exacerbated by stress, fatigue, and lack of sleep. Tic episodes occur in bouts, which also often cluster. The pattern of tics is highly unique to the person. Most cases are diagnosed by 11 years of age. Often, as children with Tourette’s disorder become older, they develop a sense that a tic is about to happen and may be able to exert some control over them, although this also serves as a source of anxiety and worry and can require much effort. The unusual behaviors are often very noticeable to others (as well as to the individual) and may pose significant problems. It is usual for attentional problems to be noted before the tics develop, but the obsessive-compulsive symptoms usually develop somewhat later, often around the same time the tics become most severe.

The severity of the tics waxes and wanes, and the tics themselves are highly variable. Tic episodes tend to happen in bouts, and these bouts themselves may cluster together. Individuals with tic disorders are very sensitive to stress, and a vicious cycle of tics leading to stress leading to more tics can be observed.

FIGURE 13.1. Plot of mean tic severity, ages 2 to 18 years. The solid line connecting the small circles plots the means of the annual rating of relative tic severity scores (ARRTS) recorded by the parents. The dashed line represents a mathematical model designed to best fit the clinical data. Two inflection points are evident that correspond to the age of tic onset and the age at worst-ever tic severity, respectively. (Adapted with permission from Leckman, J. F., Zhang, H., Vitale, A., et al. (1998) Course of tic severity in Tourette syndrome: the first two decades. Pediatrics, 102(1 Pt 1):14-19.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|