Vignette 1

Narcolepsy—Unequivocal Diagnosis After Split-Screen, Video-Polysomnographic Analysis of a Prolonged Cataplectic Attack

Video Vignette 1

Video Vignette 1

A 30-year-old man presented with a 6-year history of excessive daytime sleepiness evidenced as frequent sleep attacks, even while eating and standing.1 He also suffered frequent 5- to 45-minute spells, precipitated by laughter, that at onset were associated with facial movements followed by an inability to stand secondary to weakness.

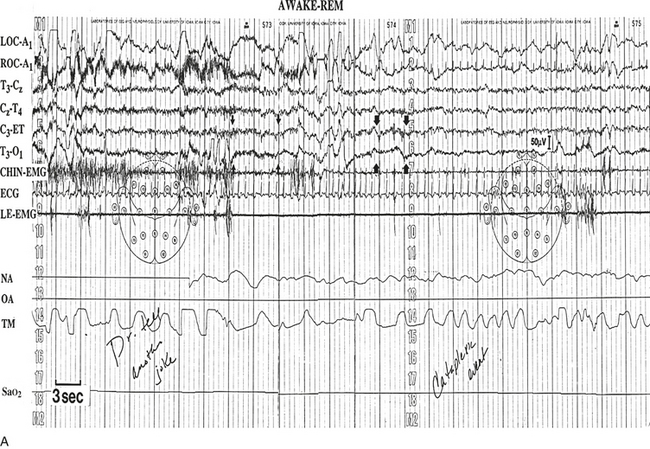

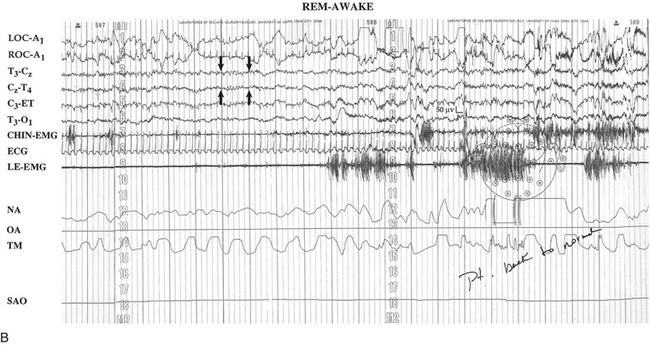

In the sleep laboratory at approximately 12:21:40 PM, a typical paretic event was precipitated after a joke as the patient was lying in a recliner (a preventive/safety measure) while being monitored under a standard polysomnogram (PSG). Given the nature of the joke, parts of it have been edited on the video. At the onset of the event his head fell back and eyes closed while facial twitching was noted, and he continued to converse in a coherent, albeit very dysarthric, manner. Simultaneously the electroencephalogram (EEG) of the PSG showed a loss of normal 8- to 13-Hz occipital alpha activity and the onset of typical low-amplitude, mixed-frequency slow alpha/theta (4 to 7.5 Hz) activity of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, which generally appears 1 to 2 Hz slower than the waking alpha rhythm (Vignette Fig. 1.1, A).2,3 Throughout REM there was a paucity of sleep spindles and K complexes. There were also intermittent sawtooth waves (trains of sharply contoured, serrated, 2- to 6-Hz waves) over the vertex region (Vignette Fig. 1.1, B).4 There was a marked reduction in electromyographic (EMG) activity, with bursts of muscular activity strongly associated with rapid eye movements.

VIGNETTE FIGURE 1.1 A, Immediately after being told a joke, a 30-year-old patient with what proved to be narcolepsy, became clinically quadriparetic. Polysomnography revealed a marked reduction of electromyographic activity with occasional bursts of muscle activity that occurred in strong association with rapid eye movement (REM) noted on the electro-oculogram. Concomitantly the electroencephalogram (EEG) revealed the sudden loss of normal waking 8- to 13-Hz alpha activity (outlined by the four small arrows), with replacement by the typical slow alpha/theta patterns of REM sleep (outlined by the four large arrows). B,: During polysomnographic REM, the patient intermittently exhibited classic 2- to 6-Hz sawtooth EEG patterns in the vertex regions (outlined by the four arrows). After conversing in a very coherent manner for approximately 7 minutes, he suddenly regained the capacity for movement, while the EEG simultaneously returned to a normal waking pattern. LOC, Left outer canthus; ROC, right outer canthus; ET, ears tied; EMG, electromyogram; ECG, electrocardiogram; LE, lower extremity. (Modified with permission from Dyken ME, Yamada T, Lin-Dyken DC, et al. Diagnosing narcolepsy through the simultaneous clinical and electrophysiologic analysis of cataplexy. Arch Neurol. 1996;53:456-460.)

During the episode the patient verbalized that this was a typical spell and that he was having no dreamlike hallucinatory experience. At 12:22:36 PM, when asked “Are you paralyzed?” he responded, “Yeah.” At 12:23:02 PM, when asked “Are you sleepy?” he responded, “Not really.” At 12:23:17 PM, in reference to the joke that precipitated the spell, he commented, “It cracked me up.” At 12:23:32 PM, when queried why the event occurred just before the punch line, he responded, “Anticipation.” He indicated continued joking could worsen the spell, but nothing specific would end it. At 12:28:42 PM the PSG spontaneously reverted to a waking pattern, paralleling a return of volitional movement and normal speech (see Vignette Fig. 1.1, B).

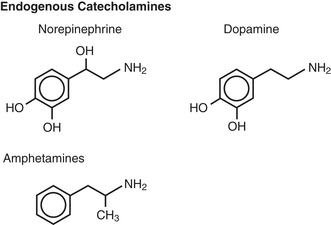

Subsequent evaluation included an overnight PSG, remarkable for a reduced sleep efficiency, a multiple sleep latency test with two sleep-onset REM periods, and a 48-hour EEG that revealed multiple episodes of a REM “sleep” pattern, after which the patient reported subjective episodes suggesting cataplexy, sleep paralysis, hypnagogic hallucinations, and sleep attacks. After starting dextroamphetamine, 15 mg orally three times a day, and imipramine, 150 mg orally twice a day, he reported feeling “100 times better” (Vignette Figs. 1.2 and 1.3).

VIGNETTE FIGURE 1.2 The chemical structures of central nervous system stimulant medications, such as amphetamine and amphetamine-like stimulants, are similar to the endogenous catecholamines norepinephrine and dopamine, which are used by the intrinsic central physiological waking systems. (Modified with permission from Dyken ME, Yamada T, Ali M. Treatment of hypersomnias. In: Kushida CA, ed. Handbook of Sleep Disorders. 2nd ed. New York: Informa Healthcare; 2009:299-319).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree