INTRODUCTION

The medical interview, the major medium of patient care, is of central importance to practitioners. A successful interview elicits accurate and complete data. It represents a dialogue that determines whether the patient agrees to take a medication, undergo a test, or change a diet. More than 80% of diagnoses are derived from the interview. The doctor–patient interaction is the keystone of patient satisfaction; moreover, interview-related factors impact major outcomes of care, including physiologic responses, symptom resolution, pain control, functional status, propensity to sue in the event of an adverse outcome, and emotional health. The medical interview also influences the quality of care, including malpractice suits and their resolution, the amount of patient disclosure of difficult or stigmatized information, time efficiency, and the elimination of “doorknob” questions as the interview ends.

Clearly, the interview is a major determinant of professional success. Yet, fewer than 10% of medical practitioners have spent time, since medical school, working on their interviewing ability. When asked, most physicians indicate that they have no plan or approach to monitoring, maintaining, or improving this critical skill. Can you imagine a professional musician, athlete, or pilot not practicing? One would question their commitment and competence or potential for remaining successful.

The interview is also key to a practitioner’s sense of professional well-being, as it is the factor that most influences satisfaction with each encounter. Physicians with high career dissatisfaction most often attribute this to unsatisfying communication and relationships with patients. Physicians with high job satisfaction have a significant interest in the psychosocial aspects of care, relate effectively with patients, and are able to manage difficult patient situations.

The central role of the interview derives from its epidemiology as well as its “one-on-one” impact. For most physicians, it is more prevalent than any other activity in their work or their lives. The average length of time per ambulatory patient visit for internists, family practitioners, and pediatricians is about 20 minutes, and these groups account for 75% of doctor visits. The average visit time for all physicians is 6 minutes, a rate curiously constant in the United States, the United Kingdom, The Netherlands, and elsewhere. Physicians who bring the average down to 6 minutes are moving scarily fast.

Making conservative estimates about how many hours a practitioner will work over a 40-year professional lifetime, a generalist will have around 250,000 patient encounters. Each interview can be the source of satisfaction or frustration, of learning or apathy, of efficiency or wasted effort (Table 1-1), of personal growth and inspiration or dispiriting discouragement. Despite the importance of performing this complex skill expertly, few physicians plan, or even think about, how to improve patient encounters to reach the desirable goals of satisfaction, learning, and efficiency.

|

Each discipline or special interest, such as psychiatry, occupational health, women’s health, or domestic violence support has a specialized set of questions that must be asked of every patient for the interview to be complete and to elicit that patient’s particular problems. (If an interviewer were to ask every question recommended by each specialty the interview would take hours.) In most cases, these questionnaires have neither been validated nor shown to be sensitive or specific. Notable exceptions include the CAGE Questionnaire (Table 1-2), which is a highly specific, sensitive, and efficient screening test for alcoholism (see Chapter 24); the two-question depression screen (see Chapter 25); and the one-question domestic violence screen (see Chapter 38).

Rather than the use of a series of over-specific, narrowly focused questions, it is more effective to use a patient-centered approach. First, elicit the patient’s complete set of concerns and questions. Then explore the priority, negotiated problem by asking open-to-closed-ended questions to encourage elaboration on the information and elicit the needed data about each concern. Lists of open-ended questions elicit information more efficiently than lists of closed-ended questions. A patient-centered approach ensures that the patient’s concerns are understood and accepted—a predictor of increased compliance. Because open-ended questions allow the patient to frame the response, the nature of framing reveals how the patient is processing the issue under discussion information is rarely available from closed-ended questions.

This approach is efficient for several reasons. First, patients usually have a sense of what is relevant and will include key information and data not anticipated by the interviewer. A physician who is thinking of the next question rather than listening to what is being said loses the ability to attend and hear on multiple levels. If the interviewer is talking then the patient is not talking, and so, is not providing data. The physician can always refer to specific items to round out the data once the patient’s story is told. If the same format is used for each interview, the variations in responses can be attributed to the patient, thereby providing significant insight.

The evidence favoring a patient-centered approach goes beyond the practical advantages: outcomes of care are also favorable. More complete and higher quality information—with an attendant reduction in procedures and tests—reduces cost, side effects, and complications. Increased patient adherence to diagnostic and therapeutic plans leads to greater clinical efficiency and effectiveness, and patients take a more active role in their own care.

A number of factors enhance interview efficiency, a growing concern, as the corporatization of health care leads doctors and patients to experience care as more rushed. Actual visit lengths have remained constant. However, as knowledge and regulation grow exponentially, tasks to accomplish in a given visit multiply—more diseases and risks to evaluate, more treatments to choose among and explain, and more computer screens and bureaucratic hoops to negotiate. These trends will undoubtedly prove counterproductive: when the visit is jammed with too much to do, psychosocial discussion suffers. This can result in unnecessary testing, patient dissatisfaction, and hazardous or needless procedures and treatments. Challenges to efficiency and effectiveness are exacerbated when behavioral medicine is removed from the medical visit by outsourcing to an external “behavioral management” company. Then both sides compete not to care for the patient, and predictably the relationship and quality of care deteriorate.

Specific techniques enhance cost-effectiveness and efficiency. Open-ended questions allow patients to elaborate on responses, provide additional information, and make interviews shorter. “Active listening” involves listening to what is said on multiple levels—how it is said, what is included and what is left out, how what is said reflects the person’s culture, personality, mental status, affect, conscious and unconscious motivation, cognitive style, and so on. Acknowledging or repeating the essence of the information shared, whether clinical or emotional, allows the patient to feel understood and provides an opportunity to correct misperceptions. A skilled active listener acquires data quickly and continuously. Like a jazz musician, an active skilled practitioner creates a harmonious flow in sync with the patient’s themes, rhythms, and style to enhance the ability of each to contribute to the complex, shifting improvisation of the interview. The experienced listener gives his or her observations the appropriate weight of clear data, hypotheses, or biases. This creates a complex and textured portrait of the patient that can be used in generating hypotheses, crafting replies, giving information, managing affective responses and nonverbal behaviors, and questioning further.

THE STRUCTURE OF THE INTERVIEW

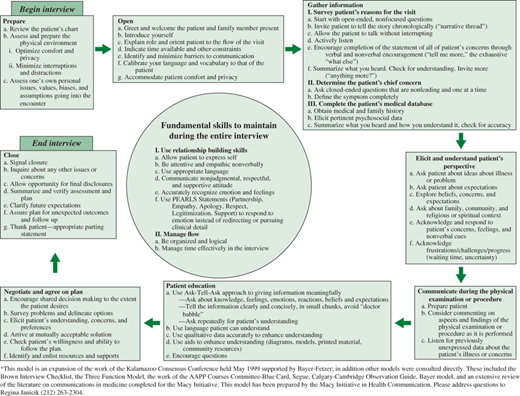

Recent literature on the medical interview runs to more than 50,000 articles, chapters, and books. Although only a modest portion of these are derived from empirical bases, sufficient work has been done to describe the interview’s conceptual framework as having “structure” and “functions.” Behavioral observations and detailed, reproducible analyses of interviews have related specific behaviors and skills to both structural elements and functions; performance of these behaviors and skills improves clinical outcomes. The following description of essential structural elements and their associated behaviors or techniques, although comprehensive, is not so exhaustive as to be impractical. Key behaviors are summarized in Table 1-3. One comprehensive model of this approach is shown in Figure 1-1.

| Element | Technique or Behavior |

|---|---|

| Prepare the environment | Create a private area. Eliminate noise and distractions. Provide comfortable seating at equal eye level. Provide easy physical access. |

| Prepare oneself | Eliminate distractions and interruptions. Focus on: Self–hypnosis Meditation Constructive imaging Let intrusive thoughts pass. |

| Observe the patient | Create a personal list of categories of observation. Practice in a variety of settings. Notice physical signs. Notice patient’s presentation and affect. Notice what is said and not said. |

| Greet the patient | Create a flexible personal opening. Introduce oneself. Check the patient’s name and how it is pronounced. Create a positive social setting. |

| Begin the interview | Explain one’s role and purpose. Check patient’s expectations. Negotiate about differences in perspective. Be sure expectations are congruent with patient’s. |

| Detect and overcome barriers to communication | Be aware of and look for potential barriers: Language Physical impediments such as deafness, delirium Cultural differences Psychological obstacles such as shame, fear, and paranoia |

| Survey problems | Develop personal methods to elicit an accounting of problems. Ask “what else” until problems are described. |

| Negotiate priorities | Ask patient for his or her priorities. State own priorities. Establish mutual interests. Reach agreement on the order of addressing issues. |

| Develop a narrative thread | Develop personal ways of asking patients to tell their story: When did patient last feel healthy? Describe entire course of illness. Describe recent episode or typical episode. |

| Establish the life context of the patient | Use first opportunity to inquire about personal and social details. Flesh out developmental history. Learn about patient’s support system. Learn about home, work, neighborhood, and safety issues. |

| Establish a safety net | Memorize complete review of systems. Review issues as appropriate to specific problem. |

| Present findings and options | Be succinct. Ascertain patient’s level of understanding and cognitive style. Ask patient to review and state understanding. Summarize and check. Tape interview and give copy of tape to patient. Ask patient’s perspectives. |

Negotiate plans | Involve patient actively. Agree on what is feasible. Respect patient’s choices whenever possible. |

| Close the interview | Ask patient to review plans and arrangements. Clarify what patient should do in the interim. Schedule next encounter. Say good–bye. |

Architects and designers believe that form follows function. Similarly, how practitioners organize their physical environment reveals core characteristics of their practice: how they view the importance of the patient’s comfort and ease; how they want to be regarded; and how they as practitioners control their own environment. Does the patient have a choice of seating? Do both patient and provider sit at comparable eye level? Is the room accessible, quiet, and private? Optimal environments reduce anxiety and instill calm and a sense of well-being.

Humans can process about seven bits of information simultaneously. Given this limitation, it is advisable to consider how many of these bits are consumed by distractions or trivia in a clinical encounter. The hypnotic concept of focus or the recently accepted psychological concepts of centering or flow apply to the clinical encounter (see Chapter 5). Thoughts about the last or next patient, yesterday’s mistake, last night’s argument, passion, or movie can affect concentration; information and opportunity are lost. In contrast, a focused practitioner, without external or internal distractions, can expect the interview to be a challenging, fascinating, and unique experience.

Achieving a focused state of mind is personal and related to each situation. Nevertheless, successful centering includes: eliminating outside intrusion by beepers and phone calls, tuning out extraneous sound, eliminating internal distraction and intrusive thoughts by resolving not to work on other matters, letting intrusive thoughts simply pass through your mind for the moment, and controlling distracting reactions within the interview by noting them, considering their origins, and putting them aside.

Such skills do not just happen. We teach our residents self-hypnosis; practitioners are routinely and efficiently able to get to a place of heightened, alert, and energetic focus. Using this skill together with the suggestions in Table 1-4, practitioners can enhance the opportunity for something profound to happen in each patient encounter.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree