INTRODUCTION

Our experience of health, illness, and health care, as patients and as practitioners, occurs in a social context. The “family” is at the heart of that context. Making the patient’s social context an explicit part of medical care affects every step of the clinical process, from basic assumptions about who the patient is to the conceptual framework for the database, theories of causality, and the implementation of treatment. Consider the following vignettes:

Despite wondering whether she could have done something more for Joe, the doctor is gratified and reassured by the family’s overwhelming thanks for the “wonderful care” she provided for the past 10 years, and in particular during the time preceding the patient’s death. The family is grateful for her help in family discussions about end-of-life care.

Eric is a 40-year-old man with diabetes who has extraordinary difficulty following a reasonable diet. His partner has been unwilling to change his expectations about their meal plans and he has been unable to negotiate a change with him.

Mary, 50 years old and previously without complaints, presents with headaches that have been ongoing for 2 months. She is afraid she has a tumor or “something bad.” A brief discussion about her family reveals that her 60-year-old husband has been depressed and forgetful for at least 6 months. Two months ago he got lost on his way home from the hardware store. After her doctor listens to her story, she agrees that she too is depressed and very concerned about her husband. She is upset that he has refused to see a doctor. She accepts her doctor’s offer to help her get him evaluated, but she is still worried that her headache is something bad.

Eva, who is 27 years old, has multiple somatic complaints and panic disorder. She was raised by her grandmother after her mother died, and when her grandmother died 4 years later, by an aunt 20 years her elder. She and her aunt became very close, “almost like sisters, we did everything together.” After completing college she returned to live with her aunt, who had recently begun the first serious relationship of her life. Eva does not understand why her aunt needs a boyfriend, and reports that her panic attacks often interrupt her aunt’s plans to spend time alone with her fiancé.

In every case, the family context is critical to understanding the situation. In the case of Joe, the doctor has attended to both patient and family and the family is a partner in care and grief. Family function has become a significant barrier to critical self-care for Eric. Mary is having a psychophysiologic reaction to family stress. Eva is a vulnerable young woman whose panic disorders are not only partially a response to her aunt’s perceived abandonment but also a high-cost and inadequate “solution.”

All health care providers have an intuitive understanding about “the family” and how families work and develop. However, lack of clinically useful tools for making the family an explicit part of care may prevent successful application of this knowledge. Caring for the patient in the context of the family goes beyond involving some families in the management of care. Two case illustrations are presented throughout the chapter that will illustrate the conceptual foundation and basic skills of family assessment and intervention.

THE FAMILY AS THE CONTEXT OF ILLNESS

The family is the primary social context of experience, including that of health and illness. The individual’s awareness and perception of health and disease are shaped by the family, as are decisions about whether, how, and from whom to seek help. Use of health care services and acceptance of and adherence to medical treatments are all influenced by the family.

There is a reciprocal relationship between healthy family systems and the physical and mental health of its members. Physical symptoms and illness can significantly influence the family’s emotional state and behavior, often causing dysfunction in family relationships; and dysfunction in the family system can generate stress and lead to physical illness. Dysfunctional family systems can incorporate a physical illness and symptoms into the family’s behavioral patterns, thereby reinforcing the sick role for one or more members and sustaining or exacerbating illness and symptoms. In these “somatizing” families, the presence and persistence of the symptom or illness cannot be understood without examining its meaning in the context of the family.

Our understanding of family is based on our experience with our own family and experiences with the families of others. The variety of groups that make up a family is enormous: two-parent nuclear families, single-parent families, foster parents with children from different biological families, families of divorcees blended through remarriage, families with gay or lesbian couples as parents, and married or cohabiting couples without any children. In some cultures, the “family” may be other members of the clan who are not related by blood or marriage. Isolated elderly individuals may think of their home health attendants as family, and for other solitary individuals the only family they may know is their pets.

All of these groups can be experienced as families. They share similarities in the structure of the relationships between their members and the role that the family group plays for the individuals and for the society in which the group exists. So, rather than define the family in terms of its members, we describe it as a system having certain functional roles.

Family relationships are described more by their roles than by the labels traditionally applied to individuals. For example, in one family an elderly woman may obtain companionship and emotional support from a home health attendant, a friend at the local senior citizen’s center, and a daughter, whereas a woman in another family may find these needs met by her marital partner. In one society, the primary education and socialization of children may be accomplished in the household of the child’s parent(s) and in community schools. In another, parent collective or unrelated individuals may accomplish these educational tasks, and play a more prominent, family-like role in children’s lives. Hence, for health care practitioners, the patient’s family context must be understood as the individuals in the social system, who are involved in the roles and tasks that are of central importance to the patient (Table 11-1).

Families as systems are characterized by:

External and internal boundaries;

An internal hierarchy;

Self-regulation through feedback;

Change with time, specifically family life cycle changes.

The qualities of these four system characteristics in a particular family help shape the family’s internal milieu and functioning.

The family is partially separated from the outside world by a set of behaviors and norms that are embedded in specific cultural systems. Family boundaries are created by norms that determine who interacts with whom, in what way, and around what activities. For example, teaching children “not to talk to strangers” creates a boundary around the family. Different parts of the family system (i.e., subsystems), such as “the parents” and “the children,” or each “individual,” are separated from one another by boundaries. Internal boundaries work in the same way: children who speak back to a parent may be told that they “don’t know their place”; they have crossed a boundary that defines their role. Healthy boundaries balance the individual identity of family subsystems with the openness required for interaction and communication across boundaries.

Subsystems of the family relate to one another hierarchically: parents have authority over the children, the older children over the younger children, and so on. A healthy hierarchy is clear and flexible enough to evolve with the needs of the family, and localizes power and control in those who are the most competent. Hierarchies may become dysfunctional for a number of reasons; for example, when they are unable to adapt to change, when the allocation of power or authority is not consistent with the location of expertise or competence in the family, or when the lines of authority are blurred and effective decisions cannot be made.

Relationships within the boundaries of the family system and its subsystems are regulated by “feedback.” All behaviors in the family set a series of actions in motion that in turn influence the original actor.

Feedback maintains the integrity of the family system as a unit, establishes and maintains hierarchies, and regulates the function of boundaries in accordance with the individual family’s norms and style. This tendency toward maintaining “homeostasis” is critical. All family systems must learn to balance the desire for stability with the inevitable need to evolve and change.

The family must continually adapt as its members evolve both biologically and socially (Table 11-2). For example, the family with young children must protect them within the boundaries of the family (or that of specific delegates, such as the schools). Adolescents need to achieve a degree of independence and the ability to function without immediate adult supervision. To facilitate this, the family must develop new norms of behavior and relax the boundary between the child and the world and redraw the boundaries between parent and child (e.g., provide more areas of autonomy and privacy). Each stage of the family life cycle presents new challenges, and healthy families are able to modify their hierarchic relationships and boundaries. Families whose boundaries, hierarchies, and self-regulatory feedback are dysfunctional have difficulties at each transition.

| Life Cycle Stage | Dominant Theme | Transitional Task |

|---|---|---|

| The single young adult | Separating from family of origin | Differentiation from family of origin Developing intimate relationships with peers Establishing career and financial independence |

| Forming a committed relationship | Commitment to a new family | Formation of a committed relationship Forming and changing relationships with both families of origin |

| The family with young children | Adjusting to new family members | Adjusting the relationship to make time and space for children Negotiating parenting responsibilities Adjusting relationships with extended families to incorporate parenting and grandparenting |

| The family with adolescents | Increasing flexibility of boundaries to allow for children’s independence | Adjusting boundaries to allow children to move in and out of the family more freely Attending to midlife relationship and career issues Adjusting to aging parent’s needs and role |

| Launching children | Accepting exits and entries into the system | Adjusting committed relationship to absence of children in the household Adjusting relationships with children to their independence and adult status Including new in-laws and becoming grandparents Adjusting to aging or dying parents’ needs and role |

| The family later in life | Adjusting to age and new roles | Maintaining functional status, developing new social and familial roles Supporting central role of middle generation Integrating the elderly into family life Dealing with loss of parents, spouse, peers; life review and integration |

Behavior in social settings can be understood in terms of “roles” that are shaped by shared expectations, rules, and beliefs. All roles have prerequisites, obligations, and benefits or dispensations. One such role is the “sick role,” which is temporarily and conditionally granted to individuals when they have an illness perceived to be beyond their control, seek professional help and adhere to treatment, and accept the social stigma associated with being sick. Individuals in the sick role are exempt from many of their usual obligations and entitled to special attention and resources. The sick role therefore has a profound effect on relationships within the family.

The exemption from obligations that is part of the sick role is critical to recovery from illness and adaptation to disability. The obligations and stigmatization of the sick role are important to protect others from abuse. Physicians play a critical role in establishing the legitimacy of the sick role by certifying the prerequisite illness or disability, and attesting to adequate adherence to treatment. Because the sick role has such a profound effect on the family of the sick individual, physicians’ obligate role in establishing the sick role makes them a powerful actor in the patient’s family system, and makes the family system an intrinsic part of the doctor–patient relationship, whether the physician is aware of these ramifications or not.

A positive relationship with an active and concerned family can be one of the physician’s most powerful tools and rewarding clinical experiences. In these circumstances, working with the family seems quite natural and the complexities of the doctor–patient–family relationship are not apparent. On the other hand, when significant family problems exist, the doctor–patient relationship can become entangled in the family system’s dysfunction.

When one or more members have assumed the sick role in response to family problems, the task of providing appropriate care for the patient may be subverted and subsumed by family dysfunction. Some families can achieve internal stability and meet the needs of their members only when one or more individuals are perceived as being sick.

The physician’s role in determining that the patient is entitled to the special prerogatives and dispensations of the “sick role” makes the physician a central and powerful member of these family systems. The authority to prescribe changes in role function for the patient further involves the physician in the life of the entire family. In effect, the physician and patient develop an alliance that compensates for the dysfunction and deficit at home. Hahn, Feiner, and Bellin have termed this a compensatory alliance.

When the physician is unaware of underlying family dysfunction, the compensatory alliance can become dysfunctional and contribute to somatization and noncompliance, and support the ultimately inadequate coping mechanism afforded by the sick role.

PATIENT CARE IN THE CONTEXT OF THE FAMILY: FAMILY ASSESMENT & INTERVENTION FOR PRIMARY CARE

Treating the patient in the context of the family requires a practical method that can be learned and used by health care providers in real world practice and training. The large number of tasks that occupy the provider places limits on the complexity of and time available for family assessment and intervention. A family assessment and intervention method must be focused, time efficient, and consistent with the general scope of care.

All patients should receive a “basic” family assessment that allows the doctor to understand how the family milieu will influence the basic tasks of care, and that identifies family problems requiring intervention (Table 11-3). Basic family assessment consists of two processes: (1) conducting a genogram-based interview and identifying the relevant family life cycle stages, and (2) screening for family problems that are associated with family life cycle stage tasks, or the patient’s medical problems. A subset of patients with problems rooted in serious family dysfunction will then require the four-step family intervention described below.

|

Treating the patient in the context of the family does not necessarily mean bringing the family into the examining room and in adult medicine usually does not. Family assessment and intervention can be accomplished by meeting exclusively with the patient, though meeting with other family members is very often desirable, sometimes necessary, and almost always enhances the care. Using a family systems orientation without meeting directly with other family members requires the ability to explore the life of the family and bring the family into the room through the patient’s narrative.

The genogram-based interview, described below, is a powerful technique for accomplishing this goal. However, the task of understanding the patient’s family system in this way can be complicated by the fact that patients often give a distorted and incomplete presentation of family life. Such distortion may be conscious, unknowing, or some of both. Therefore, clinicians need to learn to infer what is going on at home—to “see the family over the patient’s shoulder”—by imagining how members of the patient’s family might be reacting or behaving in ways that the patient does not understand or would not report.

BASIC FAMILY ASSESSMENT: CONDUCTING A GENOGRAM-BASED INTERVIEW, IDENTIFYING FAMILY LIFE CYCLE STAGE ISSUES, & SCREENING FOR PROBLEMS

CASE ILLUSTRATION 1

CASE ILLUSTRATION 1

Ariana is a 40-year-old Italian-American woman with multiple somatic complaints. She has complained of chronic diarrhea, dyspepsia, and “asthma” but has had a thorough normal gastrointestinal (GI) and pulmonary evaluation. She has made multiple visits to her primary provider and to an urgent care clinic, has been hospitalized two times, and has been seen in several subspecialty clinics. She has made an average of 15 visits per year for the past several years.

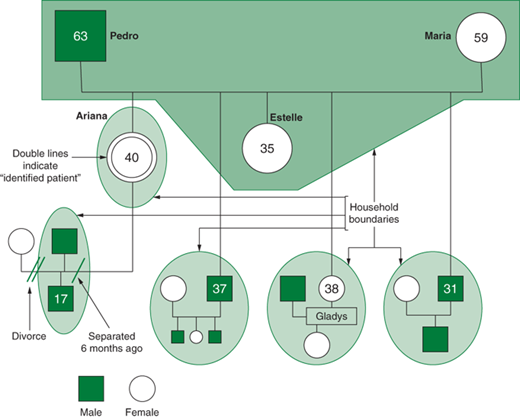

The first step to treating the patient in the context of the family is to create a picture of the family by conducting a “genogram-based interview.” A genogram is a graphic representation of the members of a family. It uses the iconography of the genetic pedigree (Figures 11-1 and 11-2) and can be used to record data ranging from family medical history to life events and employment, as well as family issues. The overall objective of the genogram interview is to help the patient tell the family’s story.

Figure 11-1.

Genogram showing household composition and key family members in Ariana’s family (Case Illustration 1).