CHAPTER 12 Couples Therapy

OVERVIEW

Couples therapy focuses on the pattern of interactions between two people, while allowing for the individual histories and contributions of each member. It is a treatment modality used in a variety of clinical situations—as part of a child evaluation (to assess the contribution of marital distress to a child’s symptoms); in divorce mediation and child custody evaluations (to minimize the intensity of relational conflict that interferes with collaborative problem solving); in ongoing child and adolescent psychotherapy (when the parents’ relationship is thought to play a part in a child’s unhappiness); and as part of an ongoing family therapy (when the couple may be seen separately from the family as a whole). Couples therapy is often the treatment of choice for a range of problems: sexual dysfunction,1 alcohol and substance abuse,2 the disclosure of an infidelity,3 depression and anxiety disorders,4 infertility,5,6 serious medical illness,7 and parenting impasses.8 In addition, couples therapy may be helpful in the resolution of polarized relational issues (e.g., the decision to marry or divorce, the choice to have a child or an abortion, or the decision to move to another city for one partner’s career). In this chapter, the term couples therapy is used rather than marital therapy so as to include therapy with homosexual couples and unmarried heterosexual couples.

SEMINAL IDEAS IN COUPLES THERAPY

The history of couples therapy is inextricably linked to that of family therapy; the two modalities draw from the same set of concepts and techniques. However, over the past 50 years couples therapy has evolved via a systemic approach to relational difficulties. While there are many theoretical schools of couples therapy (see Chapter 13 for a sampling of different approaches), most clinicians focus on several systemic principles and constructs. In the most general terms, systemic thinking addresses the organization and pattern of a couple’s interactions with one another and posits that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Systemic thinking leads the clinician to concentrate on several issues: on the communication between the couple and with outside figures; on the identification of relationship patterns that are dysfunctional; on ideas about the relationship as an entity that is greater than either member’s version; on the impact of life cycle context and family of origin on the couple’s current relational difficulties; and on some understanding about why these two people have chosen each other.

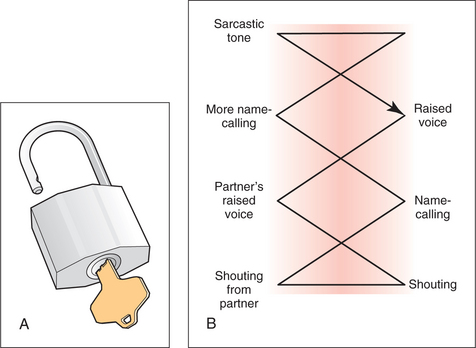

IDENTIFICATION OF DYSFUNCTIONAL RELATIONAL PATTERNS

There are two fundamental forms of relational patterns in couples (Figure 12-1): symmetrical and complementary.9 A symmetrical relationship is characterized by each member contributing a similar behavior, so that each partner compounds and exacerbates the difficulties. A classic example is one in which both members of the couple engage in verbal abuse, so that either one’s raised voice prompts an escalation of angry affect, which, in turn, triggers the other’s ire. Complementarity, by contrast, refers to patterns that require each member to contribute something quite different, in a mutually interlocking manner, to maintain the relationship. A classic example of a complementary relationship is the distancer-pursuer, in which one member does most of the asking for intimacy and connection, while the other pulls back in order to do work, take care of the children, or be alone. The circular nature of this pattern dictates that the more that one pursues, the more the other pulls back, which in turn makes the pursuer pursue more, and the distancer recoil more. Seen this way, either one could change the dance.

Over time, some therapists have questioned ideas about circularity. In particular, feminist therapists have critiqued the notion of equally shared responsibility for a problem, particularly when this notion is applied to intimate partner violence. When a partner abuses power, particularly when a man batters a woman, circular causality runs the risk of making the woman feel equally responsible for her abuse.10

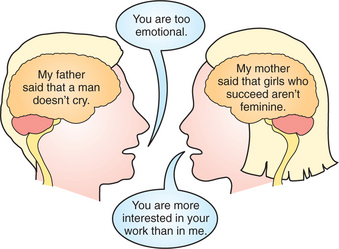

MATE CHOICE AND THE CONTRIBUTION OF ONE’S FAMILY OF ORIGIN

The couples therapist is curious about the nature of the initial attraction and may locate the origins of the current dilemma in the seeds of the couple’s first attraction. One common explanation for early attraction is that “opposites attract,” which may be understood in terms of the psychodynamic construct of projective identification.11 This is the idea that individuals look for something in the other that is difficult for them to bear or to express and then they act unconsciously to elicit the very behavior in the other that has been disavowed by the self. So, for example, a vivacious, expressive woman whose ambitions were discouraged by her family may be drawn to a cool, career-focused man whose attempts to express his feelings were ignored growing up. She may initially find his self-confidence and drive exciting, while he finds her ability to cry and to laugh invigorating. Over time, however, she may criticize him for his self-absorption, and he may criticize her for her overemotionality. In sum, what is problematic for the self, and is the initial source of mutual attraction, over time becomes played out as conflict between the couple (Figure 12-2).12

COMMUNICATION

Many couples therapists stress the importance of couples developing communication skills that allow for each partner to speak openly while the other one listens without sitting in judgment.12,13 In addition, these same therapists encourage couples to learn how to fight fairly (i.e., without blaming, name calling, or straying from the subject at hand). However, such skill training, with its emphasis on how couples talk to each other, has been transformed by social constructivists, who focus on what couples talk to each other about. These narrative therapists take as their starting point the idea that each partner’s reality is constrained by the language that he or she uses.14 Therefore, problems between partners occur because they lack the emotional vocabulary and narrative skills to create a dialogue that creates possibilities. Put simply, the way that a couple talks about a problem keeps the problem alive. Seen this way, communication about the problem is a critical place of intervention—the therapist looks for new language and stories, and reframes the issues to dissolve the couple’s view of the problem.

INTIMACY AND CONTROL

In assessing intimacy, the therapist asks about what activities are shared between the couple15 and about the quality of their connection to one another. In looking at control and power, the therapist pays attention to whether decision-making is shared or mainly determined by one partner. The therapist wonders whether the control of their relationship and issues (such as children) resides within the couple, or whether the couple must answer to other family members (such as grandparents).

Systemic theorists use several constructs to describe the interplay of intimacy and control in a relationship. Boundaries are used to describe the way that a couple defines itself as a subsystem within a family and the particular rules about how they will interact with other subsystems.16 For example, one member of a couple may wish to carve out time to vacation alone with his partner, whereas the other believes that their roles as parents always take precedence and require that the children join them. Boundaries are also described in terms of their permeability; some couples keep rigid limits on the influence others may exert on them, whereas other couples maintain very fluid boundaries with others who easily enter their relationship. Conflicts may ensue when a couple disagrees about the permeability of these boundaries or about the placement of the boundaries within the family or between the couple and the outside world.

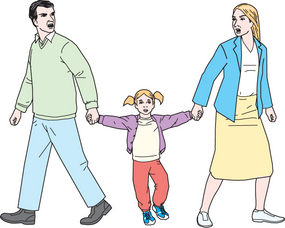

Triangulation (Figure 12-3) is another idea that describes a common reaction to the anxiety brought by dyadic closeness.17 Bowen18 posited that dyadic relationships are the most vulnerable to anxiety; consequently, it is human nature to bring in a third party to try to diffuse discomfort. The third party need not even be physically present. It may be the subject of gossip between a couple, or it may be the computer that one partner retreats to every evening after dinner, or it may be the other partner’s wish to be closer to his or her family. Bowen18 maintains that the degree to which a couple engages in triangulation is determined by previous and current involvement in intergenerational triangles. Seen this way, greater relationship closeness comes from each individual becoming more differentiated, or separate from the family of origin.

LIFE CYCLE CONTEXT AND TRANSITION POINTS

Many of the challenges that couples face occur in the context of the normative life cycle tasks. It is often in the transition from one developmental stage to the next that couples experience the most stress, as the requirements for flexibility and reorganization at a transition point may overwhelm the system. In general, each transition challenges the way the partners use their time19 and the way they need to maintain established patterns while making changes in their roles and relationships.

Life cycle theorists have delineated five stages (Box 12-1) with attendant emotional tasks.20 First comes the stage that joins families through marriage; each couple must redefine the issues and choices of their family of origin to create room for a new marital system. The next stage occurs when couples become parents. Here the main task is for the partners to make room in their relationship for new members and to redefine relationships with their extended family. The third stage is characterized by the development of the children as adolescents, when the parents must allow increased flexibility in boundaries to include adolescents’ increased independence, as well as their grandparents’ growing dependence. The fourth stage (the launching stage) occurs when young adults leave home: The main task for the couple is to reevaluate their marriage and career issues as their parenting roles diminish. Finally, the fifth stage (often the longest stage) is when the partners are on their own, after the children have left home, and the couple faces aging and loss.

BOX 12-1 Life Cycles and Transitions

| LIFE CYCLE STAGE | EMOTIONAL TASK |

|---|---|

| Redefine family of origin choices to make room for new marital system | |

| Make room in relationship for new member | |

| Redefine relationships with extended family | |

| Allow for increased flexibility in boundaries for independence of children and dependence of grandparents | |

| Reevaluation of career and marital issues | |

| Reassessment of parenting years | |

| Face loss of spouse, family, friends, health | |

| Review of life | |

| Refocus on the couple |

CONDUCTING A COUPLES THERAPY EVALUATION

A couples evaluation should allow the partners the opportunity to discuss their relational issues, as well as the individual contributions that each member makes (because of family of origin, current stressors, and intrapsychic difficulties). To provide an opportunity for joint and individual reflection, an evaluation is composed of four different meetings: the first is with both members of the couple, followed by individual meetings with each partner, and a final meeting, at which the clinician shares feedback and recommendations, with both members present (Box 12-2).