CHAPTER 13 Family Therapy

OVERVIEW

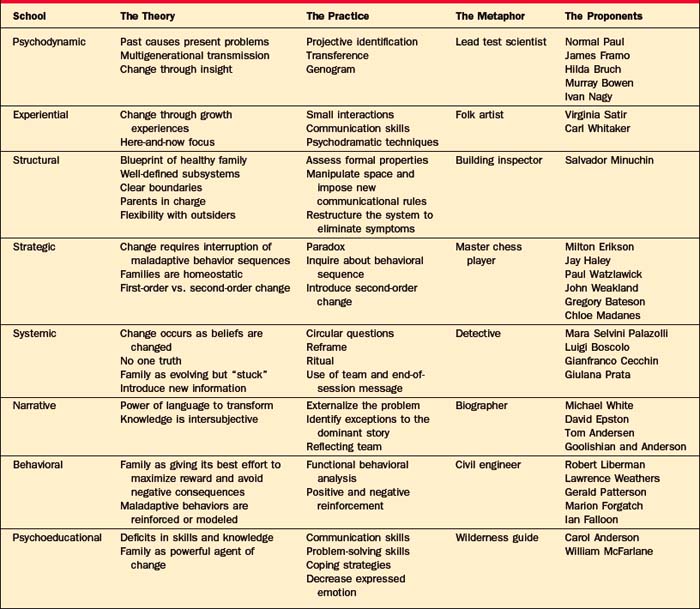

Family therapy has a rich array of approaches; to highlight them we will present a clinical vignette and illustrate how eight different types of family therapists would approach family problems.1 For each school of family therapy (Table 13-1), the major theoretical constructs, a practical approach to the family, the major proponents of that school, and a metaphor that captures something essential about that type of family therapy will be discussed. The vignette revolves around a composite family with an anorectic member. The focus is on family dynamics rather than on anorexia per se, but anorexia has been paradigmatic to family therapy, much as hysteria was for psychoanalysis or borderline personality disorder was for dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT).

PSYCHODYNAMIC FAMILY THERAPY

The Practice

In order to loosen the grip of the past on the present, the therapist uses several tools (including interpretation of transferential objects in the room, interpretation of projective identification, and the use of the genogram to make sense of generational transmission of issues). In family therapy, transferential interpretations are made among family members, rather than between the patient and the therapist, as occurs in individual therapy. For example, when Mr. Bean says “I guess I am not an expert when it comes to female problems,” the therapist may have asked, “Who made you feel that way in your family of origin?” When he reveals that he has felt this way since his sister’s suicide, he comes to understand how an old lens distorts his current vision (i.e., he still feels so guilty about his sister’s death that he does not feel entitled to weigh in with opinions about his daughter’s anorexia).

Another important tool for dredging up the past is the interpretation of projective identification, which Zinner and Shapiro2 have defined as the process “by which members split off disavowed or cherished aspects of themselves and project them onto others within the family group.” This process generates intrapsychic peace at the expense of interpersonal conflict. For example, Mrs. Bean may disown her need to control her impulses by projecting her perfectionism onto Pam. Simultaneously, Pam can disown her anger by enraging her parents with her anorexia. As these unconscious projections occur reflexively, they are more difficult for the individual to recognize and to own. Put another way, each family member behaves in such a way as to elicit the very part of the self that has been disavowed and projected onto another family member. The purpose of these mutual projections is to keep old relationships alive by the reenactment of conflicts that parents had with their families of origin. Thus, when Mrs. Bean projects her perfectionism onto Pam, she re-creates the conflict she had with her own mother, who lacked tolerance of impulses that were not tightly controlled.

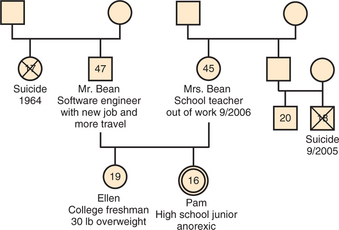

In part, the psychodynamic family therapist gathers and analyzes multigenerational transmission of issues through the use of a genogram (Figure 13-1), a visual representation of a family that maps at least three generations of that family’s history. The genogram reveals patterns (of similarity and difference) across generations—and between the two sides of the family involving many domains: parent-child and sibling roles, symptomatic behavior, triadic patterns, developmental milestones, repetitive stressors, and cutoffs of family members.2

In addition, the genogram allows the clinician to look for any resonance between a current developmental issue and a similar one in a previous generation. This intersection of past with present anxiety may heighten the meaning and valence of a current problem.3 With the Bean family (including two adolescents), the developmental imperative is to work on separation; this is complicated by the catastrophic separations of previous adolescents. Their therapist might discover a multigenerational pattern of role reversals, where children nurture parents, as suggested by the repetition of failed attempts of adolescents to separate from their parents.

The Proponents

James Framo4 invites parents and adult siblings to come to an adult child’s session; this tactic allows the past to be revisited in the present. This “family of origin” work is usually brief and intensive, and consists of two lengthy sessions on 2 consecutive days. The meetings may focus on unresolved issues or on disclosure of secrets; it allows the adult child to become less reactive to his or her parents.

Norman Paul5 believes that most current symptoms in a family can be connected to a previous loss that has been insufficiently mourned. In family therapy, each member mourns an important loss while other members bear witness and consequently develop new stores of empathy.

Ivan Boszormenyi-Nagy6 introduced the idea of the “family ledger,” a multigenerational accounting system of obligations incurred and debts repaid over time. Symptoms are understood in terms of an individual’s making sacrifices in his or her own life in order to repay an injustice from a previous generation.

Murray Bowen7 stressed the dual importance of the individual’s differentiation of self, while maintaining a connection to the family. In order to promote increased independence, Bowen coached patients to return to their family of origin and to resist the pull of triangulated relationships, by insisting that interactions remain dyadic.

EXPERIENTIAL FAMILY THERAPY

The Practice

This therapist uses psychodramatic, or action-oriented, techniques to create a new experience in the therapy session. She or he might “sculpt” the family, literally posing them to demonstrate the way that the family is currently organized—for example, with mother and Pam sitting very close together, with Mr. Bean with his back to them, and with Ellen outside of the circle. This therapist would hope to heighten feelings of frustration and alienation, and then to relieve those feelings with a new sculpture that places the parents together. These sculptures would serve to increase affect, to create some focus away from the identified patient, and to demonstrate the merits of the parents who are standing together to combat their daughter’s anorexia.

The Proponents

Virginia Satir,8 an early luminary in family therapy (a field that was largely founded by men), believed that good communication depends on each family member feeling self-confident and valued. She focused on what was positive in a family, and used nonverbal communication to improve connections within a family. If families learned to see, to hear, and to touch more, they would have more resources available to solve problems. She is credited with the use of family sculpting as a means to demonstrate the constraining rules and roles in a family.

Carl Whitaker9 posited that most experience occurs outside of awareness; he practiced “therapy of the absurd,” a method that accesses the unconscious by using humor, boredom, free association, metaphors, and even wrestling on the floor. Symbolic, nonverbal growth experiences followed, with an aim toward the disruption of rigid patterns of thought and behavior. As Whitaker puts it, “psychotherapy of the absurd can be a deliberate effort to break the old patterns of thought and behavior. At one point, we called this tactic the creation of process koans” (p. 11)9; it is a process that stirs up anxiety in family members.

STRUCTURAL FAMILY THERAPY

The Proponents

Salvador Minuchin,10,11 regarded as the founding father of structural family therapy, worked extensively while head of the Philadelphia Child Guidance Clinic with inner-city families and with families who faced delinquency and multiple somatic symptoms. Both populations had not previously been treated with family therapy. He delineated how to assess and to understand the existing structure of a family, and pioneered techniques such as the imposition of rules of communication, manipulation of space, and use of enactments to modify structure.