CHAPTER 15 Hypnosis

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Anton Mesmer and Mesmerism

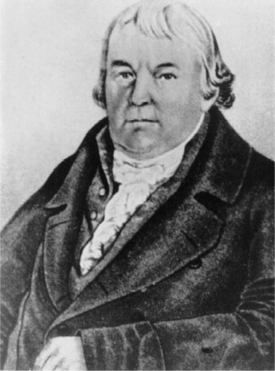

Healers of varied traditions have used suggestive therapies throughout history. The origin of medical hypnosis is generally attributed to Anton Mesmer, a Jesuit-trained eighteenth-century physician, who believed that health was determined by a proper balance of a universally present, invisible magnetic fluid (Figure 15-1). Mesmer’s early method involved application of magnets. He was an important medical figure at the Austrian court, but he fell into discredit when a scandal occurred around his care of Maria Paradise, a young harpsichordist whose blindness appears to have been a form of conversion disorder.

Mesmer reestablished his practice in Paris and employed a device reminiscent of the Leyden jar, a source of significant popular interest in the Age of Enlightenment. His patients sat around a water-containing iron trough–like apparatus (a bacquet) with a protruding iron rod. He was a colorful figure who accompanied his invocation for restored health with the passage of a wand; there was no physical contact with his patients. Susceptible individuals convulsed and were pronounced cured. An enthusiastic public greeted Mesmer’s practice and theory of “animal magnetism.” However, medical colleagues were less impressed. The French Academy of Science established a committee, led by Benjamin Franklin, the American ambassador to France, who was an expert in electricity.1 The committee found no validation for Mesmer’s magnetic theories, but determined that the effects were due to the subjects’ “imagination.”

James Esdaile, a nineteenth-century Scottish physician, was the first to take advantage of this somnambulistic state induced by Mesmerism to relieve surgical pain. Esdaile served as a military officer in the British East India Company, and took care of primarily Indian patients in and around Calcutta between 1845 and 1851. Over this period, Esdaile performed more than 3,000 operations (including hundreds of major surgeries) using only Mesmerism as an anesthetic, with only a fraction of the complications and deaths that were commonplace at the time. Many of these operations were to remove scrotal tumors (scrotal hydroceles), which were endemic in India at the time, and which in extreme cases swelled to a weight greater than the rest of the individual’s body (Figure 15-2). Before Esdaile’s use of Mesmeric anesthesia, surgery to remove these tumors usually resulted in death, due to shock from massive blood loss during the operation.2

Although Esdaile’s technique was clearly effective in many cases, it was controversial enough that, as in Mesmer’s case a century earlier, a committee was appointed and sent to India to observe Mesmeric anesthesia firsthand and to evaluate its efficacy. Esdaile performed six operations for scrotal hydroceles for the committee (which consisted of the Inspector General of hospitals, three physicians, and three judges). He carefully selected nine potential patients by attempting to induce a “Mesmeric trance” using the customary technique of passing his hands over their bodies for a period of 6 to 8 hours; as a result, three of the patients were dismissed when it was found that they could not be mesmerized even after repeated attempts over 11 days. Another three calmly faced the surgery, but when the first incision was made signaled severe pain by “twitching and writhing of their body, by facial expressions of severe pain, and by labored breathing and sighs.” The remaining three patients demonstrated to the committee “no observable bodily signs of pain throughout the operation.” Nevertheless, the committee dismissed Esdaile’s technique as a fraud and stripped him of his medical license.

Hypnosis in Psychiatric Practice

Sigmund Freud studied with Charcot, and also at Nancy.3 He was a skilled hypnotist, but he came to believe that it had an unwanted impact on transference and it was therefore incompatible with his psychoanalytic method. Instead, Freud substituted his method of free association.

Eriksonian hypnosis, named for its founder, Milton Erikson, is a counterpoint to Freud’s earlier position. Erikson advocated strategic interactions with his patients that employed use of metaphor and indirect methods of behavior shaping. While hypnotizability is generally considered to be an individual trait, Erikson believed that the efficacy of hypnotherapy depended on the skill of the therapist.4

CURRENT RESEARCH AND THEORY

Theoretical Perspectives on the Hypnotic State

Martin Orne’s5 work at the University of Pennsylvania identified the demand characteristics (based on a hierarchical relationship) of interaction between the hypnotist and the subject. He used sham hypnosis as an effective research tool. Orne also addressed the memory distortion that can occur with hypnosis and exposed its lack of validity for courtroom procedures, and he defined “trance logic” as a willing suspension of belief that highly hypnotizable subjects readily experience.

Ernest Hilgard6 and associates postulated the “neodissociation” theory of hypnosis. Hilgard saw hypnotic process as an alteration of “control and monitoring systems” as opposed to a formal alteration of conscious state. He differentiated between the unavailability of a truly unconscious process and the “split off” but subsequently retrievable material involved in dissociation.

David Spiegel7 has pointed to absorption, dissociation, and automaticity as core components of the hypnotic experience. Absorption has been found to be the only personality trait related to an individual’s ability to experience hypnosis. Table 15-1 contains several items from the Tellegen absorption scale to illustrate the characteristics of this trait.8

Table 15-1 Sample Yes/No Questionnaire Items from the Tellegen Absorption Scale