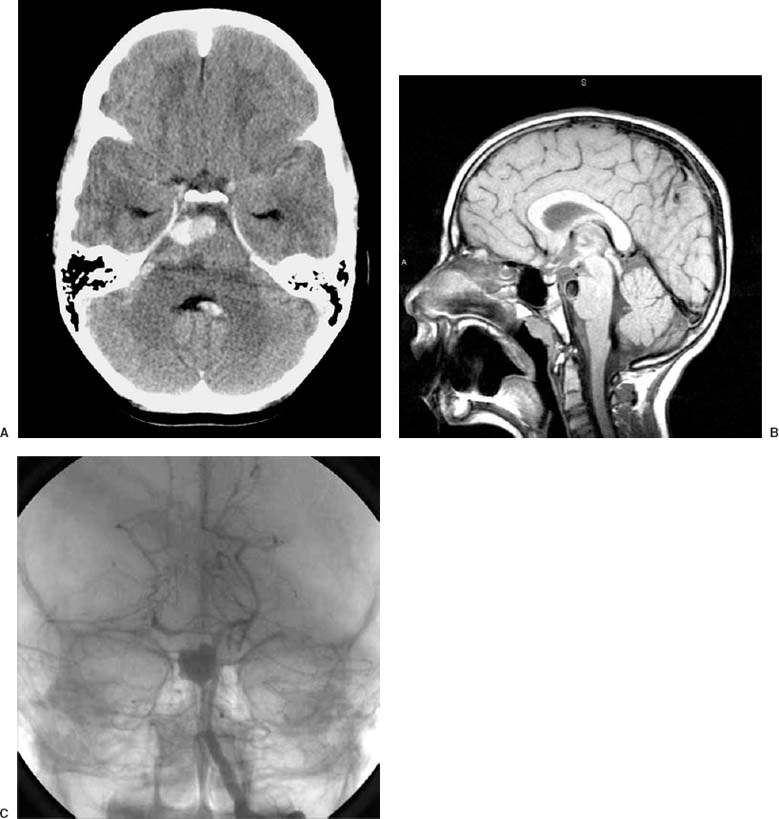

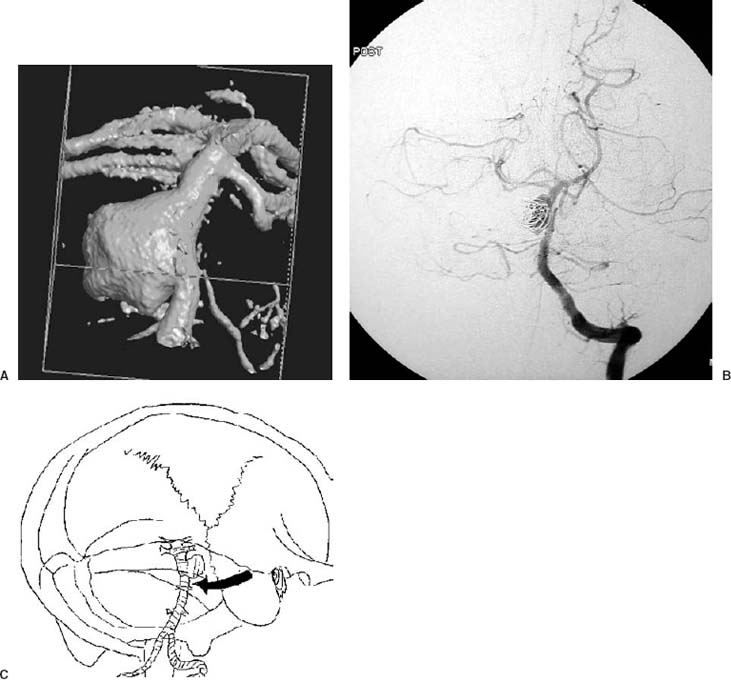

18 Diagnosis Distal basilar trunk aneurysm Problems and Tactics A large aneurysm of the distal basilar trunk was diagnosed in an 11-year-old child who presented in good condition after subarachnoid hemorrhage. The case presented particular challenges because of brain stem perforator arteries arising at and likely incorporated in the broad aneurysm neck. Acute endovascular procedure allowed partial obliteration of the aneurysm sac and protection from early rebleeding. This was followed after 1 week by therapeutic test occlusion, and successful aneurysm occlusion by hunterian clipping of the basilar artery via presigmoid retrolabyrinthine approach with preservation of hearing. Keywords Large basilar aneurysm, endovascular coiling, surgical clipping, parent vessel occlusion, presigmoid retrolabyrinthine approach This previously healthy 11-year-old boy presented with a sudden onset of severe headache, nausea, and vomiting. He had fallen during a soccer game without losing consciousness 3 days prior to his admission, and following this fall he had a headache that resolved completely. He was doing fine until 1 day prior to his admission when he had a sudden onset of severe headache in the middle of a “screaming fit.” He became lethargic and developed a progressively worsening headache, vomiting, and neck stiffness. At initial examination he was awake, alert, and oriented, with a Glasgow Coma Scale of 15 showing that cranial nerves were intact. No motor weakness or sensation alteration were found and cerebellar functions were normal. The brain computed tomographic (CT) scan showed subarachnoid blood in the prepontine cistern, with a small amount of blood in the third and fourth ventricles (Fig. 18–1A). The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) showed a large aneurysm of the distal basilar artery (Fig. 18–1B). A four-vessels angiogram was performed on the day of admission and showed a large aneurysm (~2 cm in maximal dimension) in the upper third of the basilar artery and pointing to the right, with a wide neck (Fig. 18–1C). There were prominent brain stem perforator arteries arising at the aneurysm neck, best seen with three-dimentional (3D) digital angiograhic views (Fig. 18–2A). The basilar artery filled solely from the left vertebral artery, while the right distal vertebral artery appeared atretic, terminating in the right posterior inferior cerebellar artery. FIGURE 18–1 (A) Brain computed tomographic scan without contrast showing the subarachnoid blood in the prepontine cistern and the fourth ventricle. (B) Sagittal T-1weighted magnetic resonance imaging showing the large aneurysm. (C) Angiogram, anteroposterior view, showing the large aneurysm in the upper third of the basilar artery, pointing to the right, with a wide neck. A partial endovascular coiling was performed at the day of admission with seven Guglielmi detachable coils (GDCs) placed in the distal sac of the aneurysm, intentionally stopped with subtotal coiling to avoid compromise of the basilar artery. The patient was maintained on heparin, extubated, and observed in the critical care unit. After the coiling, during the night the patient developed a left hemiparesis with lethargy. The heparin was stopped and a ventriculostomy was placed, and the patient regained full consciousness but remained hemiparetic. Two days after the coiling another cerebral angiogram revealed no interval growth of the aneurysm (Fig. 18–2B). The patient continued to improve with slowly resolving hemiparesis but no other apparent neurological deficit. FIGURE 18–2 (A) Three-dimensional digital angiographic view showing the large aneurysm with a prominent perforator close to the neck. (B) Cerebral angiogram at day 2 postcoiling showing the residual neck. (C) Schematic drawing showing the presigmoid retrolabyrinthine approach. Seven days after the admission and initial endosaccular coiling, a cerebral angiogram was repeated with the patient awake. There was no evidence of vasospasm. An endovascular balloon occlusion test of the left vertebral artery showed a persistent filling of the basilar artery from the atretic right vertebral artery. The balloon was advanced to the vertebrobasilar junction where its inflation blocked all antegrade flow into the basilar artery. The test occlusion was well tolerated clinically under full anticoagulation, with a judicious hypotensive challenge to systolic pressure of 90 mmHg. Simultaneous carotid angiography revealed filling of the distal basilar artery trunk through the posterior communicating arteries, including basilar artery branches down to the anterior inferior cerebellar arteries.

Combined Endovascular and Surgical Treatment of a Large Basilar Trunk Aneurysm in a Child

Clinical Presentation

Therapeutic Technique

First Intervention: Endovascular Protection from Early Rebleeding

Second Intervention: Endovascular Balloon Test Occlusion

Third Intervention: Presigmoid Retrolabyrinthine Approach, with Clip Ligation of the Proximal Basilar Artery (Fig. 18–2C)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree