CHAPTER 21 Mental Disorders Due to a General Medical Condition

OVERVIEW

Mental disorders due to a general medical condition (DTGMC) are defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) as psychiatric symptoms severe enough to merit treatment, and determined to be the direct, physiological effect of a (nonpsychiatric) medical condition.1 This conceptual language substitutes for previously less useful, more dichotomous terms (e.g., organic versus functional) that minimized the psychosocial, environmental influences on physical symptoms and implied that psychiatric symptoms were without physiological cause. General qualifiers further delineate mental disorders DTGMC from other co-occurring medical and psychiatric conditions. The mental disorder must be deemed the direct pathophysiological consequence of the medical condition, and must not be better accounted for by another, primary mental disorder. Symptoms that are present only during delirium (i.e., with fluctuations in the level of consciousness and cognitive deficits) are not considered DTGMC. Similarly, the presence of dementia (e.g., with memory impairment with aphasia, apraxia, agnosia, or disturbance of executive function) takes precedence over a diagnosis of DTGMC. Symptoms that are substance-induced (e.g., alcohol intoxication) do not meet criteria for DTGMC.

DISORDERS

Because affective, behavioral, cognitive, and perceptual disturbances are indistinguishable by etiology, every psychiatric evaluation should include mental disorders DTGMC in the differential diagnosis. With this rationale, most of the individual disorders are listed in DSM-IV with phenotypically similar disorders. Table 21-1 lists the various disorders under the chapter titles in which they appear in DSM-IV. Only three diagnostic entities that do not meet criteria for any particular psychiatric disorder are listed under the chapter Mental Disorders DTGMC: Catatonic Disorder, Personality Change (coded on Axis I, not Axis II), and Mental Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (NOS) DTGMC.

Table 21-1 Mental Disorders DTGMC Listed by Chapter of DSM-IV

| Delirium, Dementia, Amnestic Disorder, and Other Cognitive Disorders |

| Delirium DTGMC Dementia DTGMC Amnestic Disorder DTGMC |

| Schizophrenia and Other Psychotic Disorders |

| Psychotic Disorder DTGMC |

| Mood Disorders |

| Mood Disorder DTGMC |

| Anxiety Disorders |

| Anxiety Disorder DTGMC |

| Sexual Disorders |

| Sexual Dysfunction DTGMC |

| Sleep Disorders |

| Sleep Disorder DTGMC |

| Mental Disorders DTGMC |

| Catatonic Disorder DTGMC Personality Change DTGMC (coded on Axis I, not Axis II) Mental Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (NOS) DTGMC |

DTGMC, Due to a general medical condition.

PSYCHIATRIC DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Primary Mental Disorders

The determination of direct physiological causality is a complex issue. Table 21-2 summarizes features that should raise the clinician’s suspicion of medical causation of psychiatric symptoms. The onset of psychiatric symptoms that coincides with the onset (or increased severity) of the medical condition is suggestive, but correlation does not prove causation. Medical and mental disorders may merely coexist. The initial presentation of a medical condition may be psychiatric (e.g., depression that manifests before the diagnostic awareness of pancreatic carcinoma), or the psychiatric symptoms may be disproportionate to the medical severity (e.g., irritability in patients with negligible sensorimotor symptoms of multiple sclerosis [MS]). It also happens that psychiatric symptoms may occur long after the onset of medical illness (e.g., psychosis that develops after years of epilepsy). Psychiatric improvement that coincides with treatment of the medical condition supports a causal relationship, although psychiatric symptoms that do not clear with resolution of the medical condition do not rule out causation (e.g., depression that persists beyond normalization of hypothyroidism). There are also mental disorders DTGMC that respond to, and require, direct treatment (e.g., interictal depression), which should not be interpreted as evidence of a primary mental disorder.

Table 21-2 Features Suggestive of Physiological Causation of Psychiatric Symptoms

Psychiatric presentations uncharacteristic of primary mental disorders should raise the suspicion of a direct physiological effect of a medical condition. Features to consider include the age of onset (e.g., new-onset panic disorder in an elderly man), the usual time course (e.g., abrupt onset of depression), and exaggerated or unusual features of related symptoms (e.g., severe cognitive dysfunction with otherwise mild depressive symptoms). On the other hand, the typical features of a psychiatric syndrome support the likelihood that medical and mental disorders are co-morbid, but not causative. Such typical features include a history of similar episodes without the co-occurrence of the medical condition, as well as a family history of the mental disorder.

Substance-Induced Disorders

Many types of substances have the potential for use, misuse, or abuse. In considering the possible role of substances, clinicians should think in broad terms, and they should ask specifically about over-the-counter medications, herbal (natural or dietary) supplements, prescription medications (not necessarily prescribed for the patient), and alcohol and recreational (i.e., illegal) drugs. This detail should be routine in every evaluation, with the more selective use of blood or urine toxicology, as indicated. Symptoms may derive from substance use, intoxication, or withdrawal, and such mental symptoms may persist for several weeks after the patient’s last use of the substance.2 Substance-induced mental symptoms are not necessarily evidence of misuse or abuse. Some medications may cause symptoms when used in therapeutic doses. When such symptoms resemble concomitant disease symptoms (e.g., when a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE] develops mood lability and is on steroids), it is possible that the symptoms are both substance-induced and DTGMC, in which case the clinician should code both conditions.

General Medical Conditions

GENeral MEDical CONDITions (Table 21-3) is a mnemonic for the wide range of medical conditions that may result in psychiatric syndromes.3

Table 21-3 Categories of General Medical Conditions

| GENeral MEDical CONDITions |

| Germs (infectious diseases) |

| Epilepsy |

| Nutritional deficit |

| Metabolic encephalopathy |

| Endocrine disorders |

| Demyelination |

| Cerebrovascular disease |

| Offensive toxins |

| Neoplasm |

| Degeneration |

| Immune disease |

| Trauma |

From Beck BJ: Mental disorders due to a general medical condition. In Stern TA, Herman JB, editors: Psychiatry update and board preparation, ed 2, New York, 2004, McGraw-Hill.

Infectious Diseases

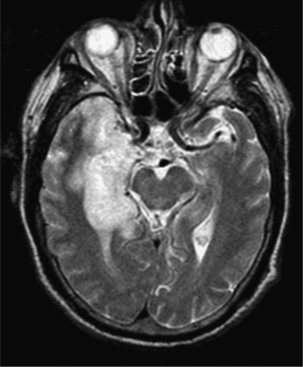

Herpes Simplex Virus (Figure 21-14)

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is the most frequent etiology of focal encephalopathy, and may cause either simple or complex partial seizures.5 With a predilection for the temporal and inferomedial frontal lobes, as illustrated in Figure 21-2,6 HSV is well known to cause gustatory or olfactory hallucinations, or anosmia (loss of the sense of smell).5 This concentration in limbic structures may also explain the personality change, bizarre behavior, and psychotic symptoms that some affected patients exhibit. Such personality changes, cognitive difficulties, and affective lability may be persistent.7 HSV-1 is responsible for most nonneonatal cases of HSV encephalitis, which does not appear to be more prevalent in the immunosuppressed population.8

Figure 21-1 Herpes simplex virus.

(From www.tulane.edu/∼dmsander/Big_Virology/BVDNAherpes.html. Courtesy of Linda Stannard, Department of Medical Microbiology, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa.)

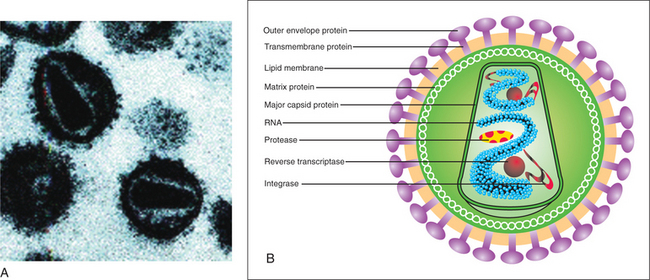

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (Figure 21-39,10)

Patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection experience a broad range of neuropsychiatric symptoms, including, but not limited to, those symptoms suggested by the various descriptors for the associated syndrome (e.g., minor cognitive/motor disorder [MCMD], HIV-associated dementia [HAD]11). Early cognitive and motor deficits involve attention, concentration, visuospatial performance, fine motor control, coordination, and speed. The dementia is characterized by short-term memory problems, word-finding difficulty, and executive dysfunction.12 Problems with sleep13 and anxiety14,15 are prevalent in the HIV-infected population. There may also be depressed mood16 and an array of associated symptoms that resemble the neurovegetative symptoms of depression (e.g., apathy, fatigue, social withdrawal, and a lack of motivation or spontaneity). Mania and hypomania occur, though less frequently.17 New-onset psychosis is uncommon and generally seen only in advanced stages of disease,18 at which point patients may also develop seizures, agitation, severe disinhibition, and mutism.

(A, From the Department of Microbiology, University of Otaga, New Zealand, www.virology.net/Big_Virology/BVretro.html. B, From the AIDS Action Coalition, www.aidsactioncoalition.org/images/hiv_virus.gif.)

The causes of HIV-related neuropsychiatric symptoms are as varied as the manifestations. Direct CNS infection, metabolic perturbations, endocrine abnormalities, malignancies, opportunistic infections, and the side effects of medications may all contribute. Nor has a consistent correlation been shown between the presence, severity, or location of CNS pathology and symptomatology.19 New onset and a CD4 count of less than 600 increase the likelihood that psychiatric symptoms may be due to HIV infection (Figure 21-4),20 or to some other (HIV-related) cause (i.e., not due to a primary mental disorder).21

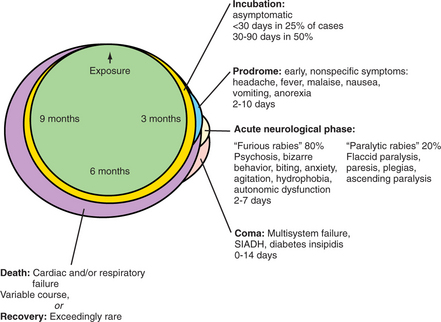

Rabies

Generally transmitted by the infected saliva of an animal bite, rabies is a viral infection of the CNS in mammals. Human cases in the United States are now so uncommon (one to two fatal cases per year since 198022) that most occur after domesticated animal bites received during travel outside of this country. By the 1970s, endemic rabies sources in the United States moved from domesticated animals (mostly dogs) to wild animals because of vaccination programs begun in the 1950s. While major wild reservoirs in the United States are raccoons, foxes, skunks, and bats, variant bat rabies forms are now responsible for most fatal, indigenous human rabies cases.23 This is significant because the variant forms may have a different course, require minimal inoculum, and cause infection in nonneural tissues. This results in a less classic, and thus unrecognized, presentation. In 2004, this difficulty in premorbid diagnosis became evident when four organ transplant recipients diagnosed with variant rabies encephalitis were traced back to single donor with a history of a bat bite.24

The average incubation time (for the more classic form of human rabies) is 4 to 8 weeks, but it is highly variable, with reports of periods as short as 10 days to as long as 1 year. The bite location, magnitude of the inoculum, and extent of host defenses are the likely determinants of the delay from contact to onset of symptoms, as the virus travels along peripheral nerves centripetally to the CNS.25,26 This variable time course and presentation are summarized in Figure 21-5. Paresthesias or fasciculations at the bite location are characteristic aspects that distinguish rabies from viral syndromes with otherwise similar prodromes. Physical agitation and excitation give way to episodic confusion, psychosis, and combativeness. These episodes, possibly interspersed with lucid intervals, are the harbinger of acute encephalitis, brain stemdysfunction, and coma. Death generally occurs within 4 to 20 days. Autonomic dysfunction, cranial nerve involvement, upper motor neuron weakness and paralysis, and often vocal cord paralysis occur. Approximately half of rabies-infected humans experience the classic “hydrophobia”27 (i.e., violent and severely painful spasms of the diaphragm, laryngeal, pharyngeal, and accessory respiratory muscles, triggered by attempts to swallow liquids).

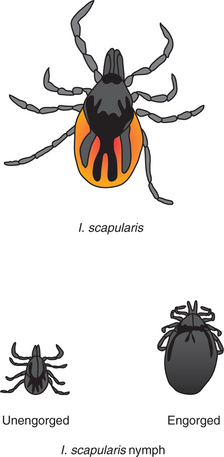

Lyme Disease

Borrelia burgdorferi is the tick-borne (specifically, Ixodes scapularis–borne [Figure 21-628]) spirochete responsible for Lyme disease, most commonly seen in the United States (Northeast, upper Midwest, and Pacific Coastal states29), as well as parts of Europe. The neuropsychiatric sequelae of Lyme disease require clinicians in all areas to have a raised level of consciousness and suspicion because the symptoms are nonspecific, highly variable, often delayed, and recurrent.30 Even when suspected, the diagnosis is difficult because of the confusing array of unreliable serologic tests (e.g., Lyme enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA], Lyme Western blot, polymerase chain reaction [PCR] assay, or culture).31

After the offending tick bite, ticks must stay attached for close to 36 hours to transmit the spirochete.32 Patients may experience a mild, flulike syndrome, and some develop a characteristic rash (erythema migrans, shown in Figure 21-733), most frequently (75% to 80% of U.S. cases with rash) a single lesion surrounding the bite. However, a more disseminated rash is thought to correspond to hematogenous spread that occurs over several days to weeks. The target sites for the spirochete include the heart, eyes, joints, muscles, peripheral nervous system, or CNS, where it may lie dormant for so long (e.g., months to years) that memory of the initial bite has long since faded.31,34 Although rapid diagnosis and aggressive antibiotic treatment are preferable to decrease chronicity, patients may still experience the onset or recurrence of symptoms months to years later.31

Figure 21-7 Typical erythema migrans rash in a patient with Lyme disease.

(From DePietropaolo DL, Powers JH, Gill JM, Foy AJ: Diagnosis of Lyme disease, Am Fam Physician 72:297-304, 2005, Figure 2.)

Fatigue, irritability, confusion, labile mood, and disturbed sleep may herald Lyme encephalitis. The much less common presentation of Lyme encephalomyelitis may be confused with multiple sclerosis. Some patients go on to develop chronic encephalopathy,31 a broad scope of persistent disturbances in personality, behavior (e.g., disorganized, distractible, catatonic, mute, or violent), cognition (e.g., short-term memory, memory retrieval, verbal fluency, concentration, attention, orientation, and processing speed), mood (e.g., depressed, manic, or labile), and thought or perception (e.g., paranoia, hallucinations, depersonalization, hyperacusis, or photophobia). Although extremely rare, more severe sequelae may include dementia, seizures, or stroke.34

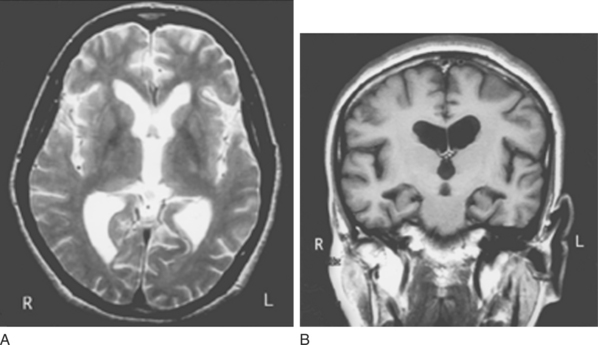

Neurosyphilis

Historically, less than 10% of patients with untreated syphilis develop a symptomatic form of parenchymatous neurosyphilis known as general paresis, 10 to 20 years after their initial infection.35 After the advent of penicillin, but before the onset of AIDS, neurosyphilis was even less prevalent. Now, there is a resurgence of a less classic form of neurosyphilis, as the use of antibiotics has altered the characteristic features.35,36 This more subtle presentation may be especially difficult to recognize by the generation of clinicians raised and educated in the relative absence of the disease. The signs and symptoms listed in Table 21-4, with the mnemonic PARESIS,37 suggest the frontal and more diffuse nature of the syndrome associated with the diffuse frontal and temporal lobe findings seen on imaging studies (Figure 21-838). Personality change may be striking, and can involve apathy, poor judgment, lack of insight, irritability, and (new onset of) poor personal hygiene and grooming. Patients may also have difficulty with calculations and short-term memory. Later signs include mood lability, delusions of grandeur, hallucinations, disorientation, and dementia.39 It is during this late stage that the classic neurological signs may appear (e.g. tremor, dysarthria, hyperreflexia, hypotonia, ataxia, and Argyll Robertson pupils [small, irregular, unequal pupils able to accommodate, but not react to light]). The diagnosis is confirmed by cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) with elevated protein and lymphocytes and a positive (CSF) Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) slide test for treponemal antibodies.40

Table 21-4 Manifestations of General Paresis

| PARESIS Personality Affect Reflexes (hyperactive) Eye (Argyll Robertson pupils) Sensorium (illusions, delusions, hallucinations) Intellect (decreased recent memory, orientation, calculation, judgment, and insight) Speech |

From Lukehart SA, Holmes KK: Syphilis. In Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Isselbacher KJ, et al, editors: Harrison’s principles of internal medicine, ed 14, New York, 1998, McGraw-Hill.

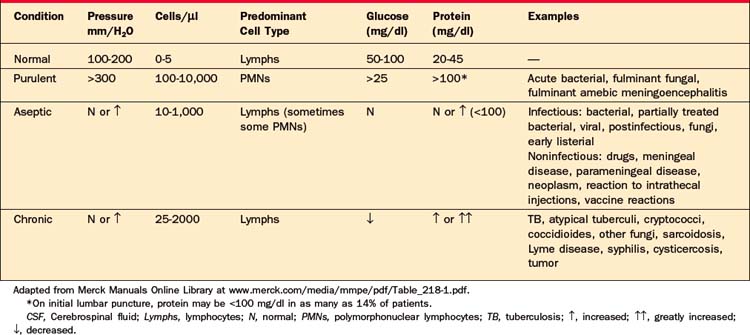

Chronic Meningitis

Although Mycobacterium tuberculosis is the most common cause,41 the fungal pathogens cryptococcus42 and coccidioides43 may also produce this subtle, nonspecific syndrome, which, if not unnoticed, may be ascribed to a primary, predisposing illness, such as AIDS. The chronic meningitides are treatable if recognized, but they often go undetected because they cause minimal signs (e.g., low-grade fever) and symptoms (e.g., mild headache), particularly in immunocompromised patients. The equally nonspecific neuropsychiatric manifestations include confusion and problems of behavior, cognition, and memory. Characteristic CSF findings, summarized in Table 21-5,44 include a primarily lymphocytic pleocytosis with decreased glucose and elevated protein.

Chronic, Persistent Viral or Prion Diseases

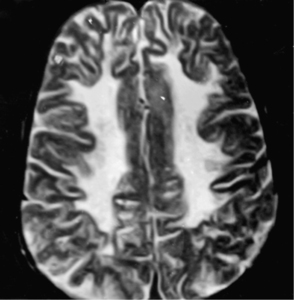

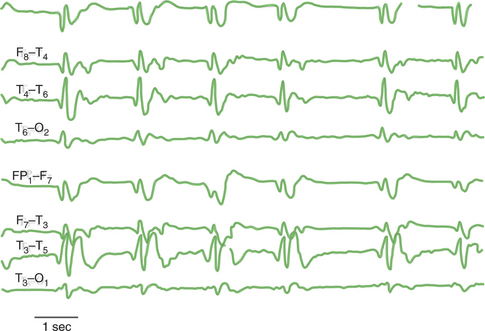

Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) is a disease primarily of children and adolescents (usually less than age 11). It occurs more often in males (3:1) after previous measles (rubeola) infection or, much less frequently, after measles vaccination. Since the advent of more pervasive measles vaccination, the incidence of SSPE has progressively decreased. The initial manifestations may be mistaken for behavioral problems, with worsening school performance, distractibility, oppositional behavior, or temper tantrums.45 Excessive sleepiness and hallucinations follow. Early imaging of the brain may be normal,46 followed by obliterated sulci and small ventricles from cerebral edema, then T2-weighted hyperintensity predominantly in the occipital lobe and subcortical white matter with relative frontal sparing, as seen in Figure 21-9.45 Within a few months, affected children may experience myoclonic jerks, ataxia, seizures, and further intellectual decline. A characteristic electroencephalograph (EEG) pattern, which corresponds to the myoclonic jerks,46 consists of bilateral, symmetric, high-voltage, synchronous bursts of polyphasic, stereotyped delta waves (Figure 21-1045). By 6 months most patients are bedridden. Death occurs within 1 to 3 years.

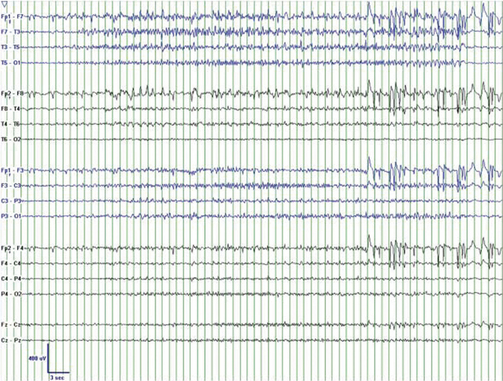

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), in contrast, is a disease primarily of 50- to 70-year-olds.47 This rapidly progressive and fatal prion disease is exceedingly rare, with most cases thought to be sporadic. Approximately 5% to 15% appear to be familial. Iatrogenic, person-to-person infection has also occurred following corneal transplantation, as well as therapeuticuse of cadaveric human growth hormone or cadaveric gonadotropins.48 A variant form of CJD (vCJD), caused by infection with the etiological prion of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE; also known as “mad cow disease”), tends to affect younger adults47 and may have person-to-person infection through blood transfusion.49 The initial symptoms of CJD may be nonspecific and include problems of cognition (memory or judgment), mood (lability), perception (illusions or distortions), or sensorimotor function (ataxic gait, vertigo, or dizziness). In vCJD, the early symptoms are more prominently psychiatric, behavioral, or both.47 More ominous signs of psychosis and confusion herald the dementia and myoclonus considered the hallmarks of CJD. Patients generally die within a year, becoming spastic, mute, and finally stuporous. Suggestive diagnostic findings late in the clinical course include cerebellar atrophy on head computed tomography (CT) scan and typical EEG changes (Figure 21-1150). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has also been found to be a reasonably sensitive and highly specific diagnostic aid,51 although finding 14-3-3 protein in the CSF may be the most discriminating evidence for the disease.52

Kuru, which translates as “to shiver with fear,” was endemic among Papua New Guinea highlanders of a particular tribe who ate the brains of their dead. The incidence of kuru, a fatal, dementing disorder with progressive extrapyramidal signs, declined along with the incidence of ritual cannibalism.53

Epilepsy

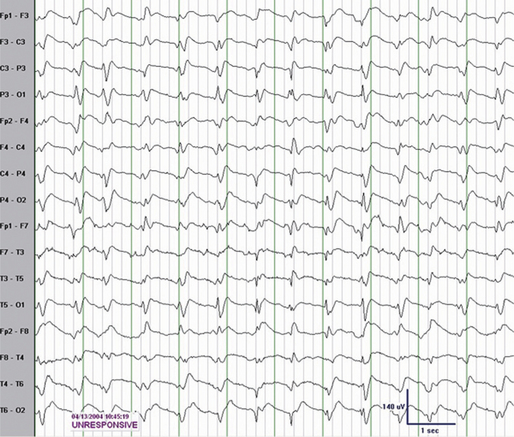

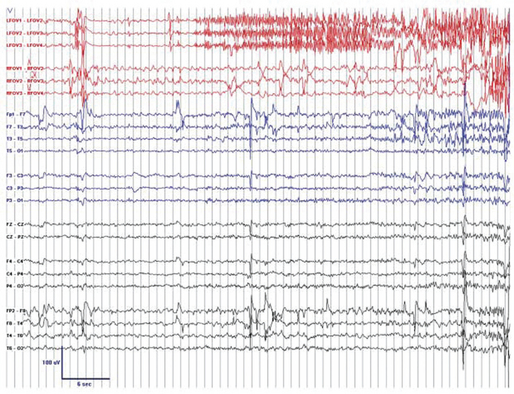

Epilepsy affects approximately 2 million Americans, and has a lifetime prevalence of 3%.54 A prime example of the need for healthy skepticism in the dichotomous view of functional versus organic, epilepsy continues to beg the mind/brain question. This common neurological (i.e., brain) disorder is now attributed to indiscriminate, haphazard, electrical misfiring of impulses in the brain cortex. However, before the use of the EEG (Figure 21-12) could correlate these disorganized electrical episodes with the resultant (motor, affective, behavioral, cognitive, memory, or perceptual) phenomena, seizures were considered to be moral, emotional, or mental (i.e., mind) infirmities.55,56 Seizure manifestations, including altered or loss of consciousness, correlate with the location of abnormal brain impulses, but these manifestations are the same, nonspecific responses that occur in response to stimulation (in the same anatomic area) from any input source. While generalized tonic-clonic motor activity is a syndrome readily recognized as a seizure, seizure-induced fear, depression,57 anxiety, or psychotic symptoms58 are indistinguishable from those of primary mental disorders. The EEG may be suggestive of seizure, but the clinical diagnosis of seizures cannot be ruled out by the lack of EEG evidence59 (Figure 21-13).

Figure 21-12 Scalp electrode EEG recording during left temporal lobe seizure.

(Courtesy of Sydney S. Cash, M.D., Ph.D., Instructor in Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School.)

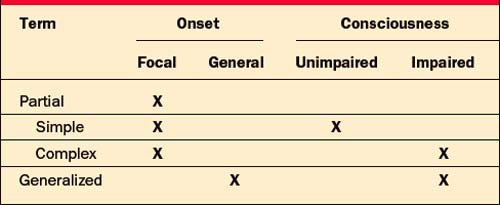

Although a number of detailed classification systems exist, and there is a movement away from the term partial (with a preference for focal),60 Table 21-6 presents a simplified and useful framework for this discussion. Partial seizures have focal onset, but may secondarily generalize. They may, or may not, cause motor or autonomic signs, as well as somatosensory or psychic symptoms. Generalized seizures include absence seizures (which may or may not include motor signs), as well as the more readily recognized convulsive seizures.61

Complex Partial Seizures

A highly underdiagnosed condition, partial seizures are responsible for most of the nonconvulsive seizures experienced by an estimated 60% of epileptics in the United States.62 These seizures often derive from deep, limbic brain structures, commonly the temporal lobe, where abnormal impulses do not transmit to the surface electrodes of the EEG in up to 40% of patients.59,63 This is further support for seizures remaining a clinical diagnosis, inferred, but never dismissed, by EEG interpretation.

Patients with epilepsy come to psychiatric attention because they have a high prevalence of psychiatric symptoms that are indistinguishable from those of primary mental disorders. Over half of epileptics experience depression, with higher rates for patients with complex partial seizures and those with seizure foci in the left hemisphere.64 In contrast, the incidence of depression in matched medical and neurological control groups is only 30%. This implies that depression may be seizure-induced limbic dysfunction, and may also explain the fivefold increase in the suicide rate for epileptic patients as compared to those in the general public. That risk may be as much as 25 times higher for patients with temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE),65 although this has not been consistently replicated.66 Patients with partial seizures also experience more anxiety than both the general public and patients with other types of seizures.58 In fact, partial seizures bear many of the hallmarks of panic attacks, and the two may be difficult to distinguish. Both may occur “out of the blue,” with hyperarousal, intense fear, perceptual distortion, and dissociative symptoms (e.g., depersonalization or derealization).67 Hyperventilation, a common symptom of panic, also lowers the seizure threshold, and may appear to initiate either event. Benzodiazepines may improve both conditions. There are features, however, that aid in the differentiation.68 Although the fear of fainting is common in panic attacks, the actual loss or alteration of consciousness is much more common in partial seizures. Mild visual or auditory distortions may occur during panic attacks, but true hallucinations (especially olfactory or gustatory) are more suggestive of seizure activity. Similarly, automatisms (chewing or lip-smacking movements) and a confusional state after the episode strongly support a diagnosis of seizure. Another helpful difference is the vivid memory of the event in panic attacks, which leads to the “fear of fear” that is classic for panic disorder and predisposes to agoraphobia and avoidance. In contrast, following a seizure, patients often have lack of awareness or partial memory of the event, and rarely develop agoraphobia. The time course is generally more defined for panic, lasting 10 to 20 minutes. Complex partial seizures, on the other hand, tend to begin with cognitive (e.g., déjà vu, jamais vu, or forced thinking), affective (e.g., fear, depression, or pleasure), or perceptual (e.g., illusions or olfactory or gustatory hallucinations) auras, then a brief cessation of activity, a minute or less of unresponsiveness and automatismic behavior, and finally a short (e.g., lasting seconds to half an hour) period of decreased or lack of awareness.

Psychotic symptoms are seen 6 to 12 times as often in epileptics than in the general population. These include, but are not limited to, the brief hallucinatory, affective, or cognitive auras, which are themselves the result of abnormal electrical impulses (i.e., seizure activity). Seizures may also be followed by postictal delirium of relatively short duration. However, after years of epilepsy, some patients develop an episodic or more chronic, unremitting psychosis with hallucinations, paranoia, and a circumstantial thought pattern58 (rather than the common schizophrenic formal thought disorders of tangentiality, derailment, and thought-blocking). The epileptic’s preserved affective warmth is in sharp contrast to the affective flattening more commonly seen in schizophrenia. This chronic psychosis, thought to be caused by subictal, temporal lobe dysrhythmias,69 is often heralded by personality change. Interictal personality traits commonly ascribed to TLE include obsessionality, dependence, hyperreligiosity, hypergraphia, hyposexuality, and humorlessness.70 However, such traits remain unsubstantiated by research with structured, diagnostic instruments.71 Less controversial is the recognized difficulty to disengage from the TLE patient’s viscous, sticky, conversational style.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree