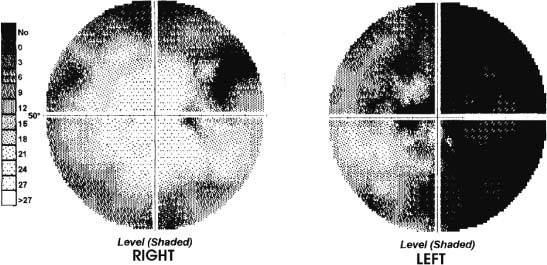

39 Diagnosis Grade 1 subarachnoid hemorrhage, vasospasm, right posterior communicating aneurysm, left A1 segment aneurysm, and apoplexy of growth hormone–secreting pituitary macroadenoma with visual failure. Problems and Tactics A 51-year-old, left-handed woman presents 4 days after collapse with headache and visual failure affecting predominantly the left eye, and is found to have a growth hormone (GH)–secreting pituitary macroadenoma, a small amount of subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), a 6-mm aneurysm of the right internal carotid artery (ICA) at the posterior communicating artery (PCoA) origin, a 3-mm left anterior cerebral artery (ACA) aneurysm at the midpoint or the A1 segment, and vasospasm. There was no indication as to which aneurysm had caused the SAH. A right pterional/subfrontal craniotomy with frontal extension allowed clipping of both aneurysms (the left A1 aneurysm approached between the optic nerves) and debulking of the macroadenoma. Keywords Aneurysm, pituitary tumor, pituitary apoplexy, subarachnoid hemorrhage, vasospasm This 51-year-old, healthy, left-handed female presented 4 days following collapse. The collapse had occurred suddenly in the shower, and the period of loss of consciousness was probably only a few minutes. On regaining consciousness she was aware of global headache and general malaise. She did not report neck stiffness or photo-phobia, although she noted her vision, which had been poor particularly in the left eye for 2 years, was blurred. She cared for herself and was fully independent until presenting to hospital with increasing headache and malaise. On examination the patient was alert with no neurological deficit except for visual signs. Visual acuity was 6/5 on the right and 6/9 on the left, a Marcus-Gunn pupillary reaction on the left, and optic atrophy on the left with normal right funduscopy. Formal field examination showed complete left temporal field loss and an enlarged blind spot on the left and some peripheral restriction (particularly upper quadrants) on the right (Fig. 39–1). There was no extraocular palsy, no other cranial nerve deficit, and no neck stiffness. There was no clinical evidence of hormonal dysfunction and, in particular, no signs of acromegaly. Computed tomographic (CT) scan revealed a 3-cm isodense mass in the pituitary region, which enhanced with contrast; a moderately enlarged sella turcica was noted on the bone views, and no evidence of subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) (Fig. 39–2A). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan confirmed the diagnosis of pituitary macroadenoma with suprasellar extension and extension into the right cavernous sinus, with no evidence of bleeding in the tumor (Fig. 39–2A–C). MRI fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images sequence showed a small amount of increased signal in the subarachnoid space in the convexity gyri and basal cisterns, indicating evidence of minor SAH (Fig. 39–2D). Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) suggested a small (6 mm) right internal carotid (posterior communicating) aneurysm, and suggested the possibility of a left A1 segment ACA aneurysm (Fig. 39–2E). Cerebral digital subtraction angiography (DSA) demonstrated a 7-mm right-sided internal carotid artery/posterior communicating artery (ICA/PCoA) aneurysm that was moderately irregular (Fig. 39–2F). In addition, there was an irregular small (3–4 mm) aneurysm arising from the midportion of the left A1 segment of the anterior cerebral artery (ACA), midway between the carotid bifurcation and the anterior communicating artery (ACoA) (Fig. 39–2G). There was evidence of vasospasm in the left A1 segment and the ACoA complex. There was also fusiform dilatation of the basilar termination but no specific saccular aneurysm at that site. FIGURE 39–1 Automated visual field perimetery (Medmont M600) at presentation. Endocrine assays revealed moderate elevation of growth hormone and mild elevation of prolactin consistent with stalk effect [prolactin 2576 mIU/L (70–700), fT4 11.0 pmol/L (9.0–26.0), TSH 5.29 mIU/L (0.1–4.0), LH 3.9 IU/L (0.5–15.0), FSH 4.0 IU/L (0.5–13.5), GH 7.1 mIU/L (0.13–5.0), cortisol 261 nmol/L (120–650)]. The patient was given a general anesthetic, with attention to maintaining mild hypervolemia (not using diuretic) and strict avoidance of hypertension to give some protection from the vasospasm. High-dose corticosteroids were given to protect the optic nerves during tumor dissection. A variation of the pterional craniotomy was used where the scalp is retracted forward with the temporalis fascia. Temporalis muscle is kept intact but is detached from its anterior cranial insertion and retracted posteroinferiorly to expose the pterion. This allows more anterior access than when the temporalis muscle is divided and retracted forward, and provides the option to convert to the frontoorbitozygomatic approach should access be restricted.1 A 6 × 9 cm free frontotemporal craniotomy flap was raised, providing low access to the anterior fossa floor. The remaining medial part of the sphenoid wing not raised with the craniotomy flap and irregularities in the floor of the anterior fossa were removed with a high-speed burr extradurally.

Subarachnoid Hemorrhage with Bilateral Aneurysms and Apoplexy of Pituitary Macroadenoma

Clinical Presentation

Surgical Technique

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree