Vignette 4

Isolated Sleep Paralysis: An REM-“Sleep” Polysomnographic Phenomenon as Documented With Simultaneous Clinical and Electrophysiological Assessment

A 29-year-old man reported spells from sleep since age 15 years, in which he arises to full consciousness from a dream “halfway being awake and still asleep” because he is essentially paralyzed.1 He stated, “I can communicate,” but he is “frightened” and can only “whisper.” An episode can resolve after he aggressively attempts to move his head or after vigorous physical stimulation by his wife. He had no other major health problems, was on no chronic medications, and reported no history of sleep attacks, cataplexy, or hypnagogic hallucinations.

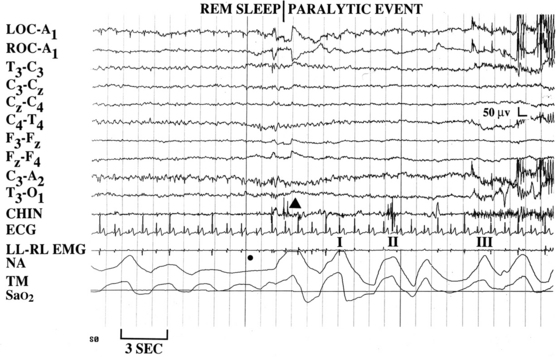

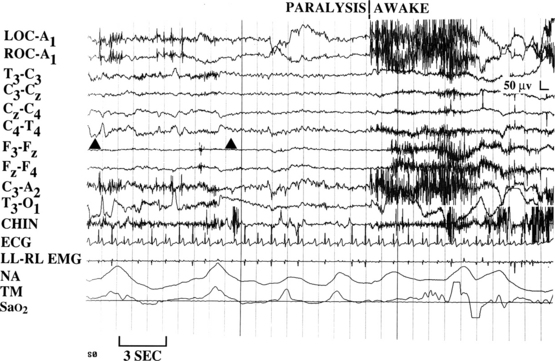

Split-screen, video-polysomnography (PSG) with an expanded electroencephalographic (EEG) montage (to rule out sleep-related seizures) was used to monitor the patient. During classic rapid eye movement (REM) sleep he had a mild hypopnea at 00:05:36 hours, followed by a snorting sound at 00:50:40, after which he said, “Help!” at 00:50:45, and then “I’m awake,” despite the persistence of a PSG REM sleep pattern at 00:50:51, a pattern that lasted throughout the entire 2-minute, 40-second event. The PSG showed persistence of a classic REM sleep pattern with a marked reduction of electromyographic activity, but occasional bursts of muscle activity in association with rapid eye movements. The EEG showed the typical slow alpha/theta patterns of REM sleep with intermittent classic sawtooth waves (trains of sharply contoured, serrated, 2- to 6-Hz waves over the vertex region) (Vignette Figs. 4.1 and 4.2).2

VIGNETTE FIGURE 4.1 This patient is a 29-year-old man whose normal waking polysomnogram (PSG) pattern stands in stark contrast to his rapid eye movement sleep, during which, after a brief hypopnea (dot) a paralytic event appears to begin with a muscle jerk (arrowhead); he calls for “help” (I), after which he states “I’m awake” (II). The split-screen video-reformatted PSG clearly shows the patient’s mouth open as he talks (in a rather dysarthric manner because of facial paresis) to the technician. He subsequently turns and shakes his head to the right (III), which is a maneuver he previously described using, attempting to end such sleep paralytic events. LOC, Left outer canthus; ROC, right outer canthus; A1, left ear; T, temporal; C, central; F, frontal; O, occipital; ECG, electrocardiogram; LL-RL, legs tied; EMG, electromyogram; NA, nasal airflow; and TM, thoracic movement

VIGNETTE FIGURE 4.2 During the event classic sawtooth waveforms can easily be appreciated (above and between the two arrowheads). When viewing the video, it can be seen that the patient’s facial expression shows extreme angst during the transition from a rapid eye movement sleep to a waking polysomnographic pattern. LOC, Left outer canthus; ROC, right outer canthus; A1, left ear; T, temporal; C, central; F, frontal; O, occipital; ECG, electrocardiogram; LL-RL, legs tied; EMG, electromyogram; NA, nasal airflow; and TM, thoracic movement.

In summary, during a REM sleep pattern the patient told the technician that this had been a typical spell, which began from a resolved dream, after which he was left fully cognizant, paralyzed, and with memory for three words recited to him during the event. Despite a successful continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) titration, the patient’s nocturnal paralytic events persisted. The patient stated that his spells had improved “tremendously” after subsequent treatment with imipramine, 100 mg every night at bedtime. In addition, the patient had positive results for human leukocyte antigen (HLA) DR2 and DQ1 typing.

Discussion

Although sleep paralysis, hypnagogic/hypnopompic hallucinations, and cataplexy are assumed to be the result of dysfunctional REM sleep, some investigators believe that a REM EEG pattern does not necessarily occur during these events because they assume the ascending sleep mechanisms should not be operative. Consequently, according to this view, cataplexy appears as a dissociated phenomenon, characterized by the isolated appearance of REM atonia associated with full wakefulness.3 At an international symposium held in Washington, DC, it was stated, “Cataplexy is associated with an ‘awake’ EEG.”4 The International Classification of Sleep Disorders has variably reported that sleep paralysis is “associated with an electroencephalographic pattern of wakefulness,” or “either intrusion of alpha rhythm into REM sleep or persistence of REM-type atonia into wakefulness.”4,5 Nevertheless, evidence that sleep paralysis, hypnagogic hallucinations, and cataplexy can occur during typical REM sleep patterns may extend the utility of prolonged PSG monitoring.1,6–12

Sleep paralysis can involve hallucinations that include an intruder, an “incubus,” or an out-of-body experience.13 A sense of terror that an intruder is present may result from mesencephalic hypervigilence.13 During an incubus hallucination the intruder attempts to suffocate the patient. Concomitant REM-related breathing problems, such as obstructive sleep apnea may exacerbate this phenomenon.13 An out-of-body floating sensation has been hypothesized to follow activation of the brainstem, cerebellum, and cortical vestibular centers.14

Although sleep paralysis is classically associated with narcolepsy, in the general population the prevalence rate of at least one episode may be up to 40%.6 There are two types of sleep paralysis, isolated and recurrent; isolated events last only minutes, whereas recurrent episodes may last hours.15 Precipitants may include stress, sleep deprivation, medications, the supine sleeping position, and apnea. Severe sleep paralysis has been treated with tricyclic antidepressants or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.16

The unequivocal diagnosis of many REM-related sleep phenomena can be greatly enhanced by a clinical evaluation during typical REM sleep patterns at the time of events captured during routine or modified PSG studies. In this vignette a mild hypopnea precipitated sleep paralysis during a REM sleep pattern in a patient without clinical narcolepsy, but with positive HLA DR2 and DQ1 typing. This case is of special interest in that successful treatment mandated the use of both CPAP and medication.Uncited