CHAPTER 45 Electroconvulsive Therapy

OVERVIEW

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) remains an indispensable treatment because of the large number of depressed patients who are unresponsive to drugs or who are intolerant to their side effects. In the largest clinical trial of antidepressant medication, only 50% of depressed patients achieved a full remission, while an equal percentage were nonresponders or achieved only partial remission.1 On the other hand, remission rates of 70% to 90% have been reported in clinical trials of ECT.2,3 Depression requires effective treatment because it is associated with increased mortality risk (mainly due to cardiovascular events or suicide).4 Furthermore, among all diseases, depression currently ranks fourth in global disease burden, and is projected to rank second by the year 2020.5 ECT is currently the most promising prospect for addressing the unmet worldwide need for effective treatment of individuals suffering from depression.

INDICATIONS

Major depression is the most common indication for ECT. The symptoms that predict a good response to ECT are those of major depression (e.g., anorexia, weight loss, early morning awakening, impaired concentration, pessimistic mood, motor restlessness, increased speech latency, constipation, and somatic or self-deprecatory delusions).6,7 The cardinal symptom is the acute loss of interest in activities that formerly gave pleasure. These are exactly the same symptoms that constitute the indication for antidepressant drugs, and at the present time there is no way to predict which patients will ultimately be drug-resistant. There is currently little consensus on the definition of drug-resistant depression,8 and the designation of drug failure varies with the adequacy of prior treatment.9 Medical co-morbidities are also important to this definition. Young, healthy patients can safely receive four or more different drug regimens before moving to ECT, whereas older depressed patients may be unable to tolerate more than one drug trial without developing serious medical complications.

Other factors also affect the threshold for moving from drug therapy to ECT. Thoughts of suicide respond to ECT 80% of the time,10 and are an indication for early transition from drug therapy.11 Lower response rates to ECT have been reported in depressed patients with a co-morbid personality disorder,12 and a longer duration of depression,13 but there is conflicting evidence in the literature as to whether a history of medication resistance is associated with a lower response rate to ECT. However, none of these factors constitutes a reason to avoid ECT if neurovegetative signs are present.

Psychotic illness is the second most common indication for ECT. Although it is not a routine treatment for schizophrenia, ECT, in combination with a neuroleptic, may result in sustained improvement in up to 80% of drug-resistant patients with chronic schizophrenia.14,15 Young patients with psychosis conforming to the schizophreniform profile (i.e., with acute onset, positive psychotic symptoms, affective intactness, and medication resistance) are more responsive to ECT than are those with chronic schizophrenia, and they may have a full and enduring remission of their illness with treatment.16–18

Mania also responds well to ECT,19,20 but drug treatment remains the first-line therapy. Nevertheless, in controlled trials, ECT is as effective as lithium (or more so), and in drug-refractory mania, more than 50% of cases have remitted with ECT.21 ECT is highly effective in the treatment of medication-resistant mixed affective states22 and refractory bipolar disorder in adolescents.23

Although most patients initially receive a trial of medication regardless of their diagnosis, several groups of patients are appropriate for ECT as a primary treatment. These include patients who are severely malnourished, dehydrated, and exhausted due to protracted depressive illness (they should be treated promptly after careful rehydration); patients with complicating medical illness (such as cardiac arrhythmia or coronary artery disease) because these individuals are often more safely treated with ECT than with antidepressants; patients with delusional depression (as they are often resistant to antidepressant therapy,24 but respond to ECT 80% to 90% of the time)25–27; patients who have been unresponsive to medications during previous episodes (because they are often better served by proceeding directly to ECT); and the majority of patients with catatonia (as they respond promptly to ECT).28–30 Although the catatonic syndrome is most often associated with affective disorder, catatonia may also be a manifestation of schizophrenia, metabolic disorders, structural brain lesions, or systemic lupus erythematosus. Prompt treatment is essential because the mortality rate of untreated catatonia is as high as 50%, and even its nonfatal complications (including pneumonia, venous embolus, limb contracture, and decubitus ulcer) are serious. ECT is effective in up to 75% of patients with catatonia, regardless of the underlying cause, and is a primary treatment for most patients with catatonia.31 Lorazepam has also been effective for short-term treatment of catatonia,32 but its long-term efficacy has not been confirmed. While neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) may be clinically indistinguishable from catatonia,33 high fever, opisthotonos, and rigidity are more common in the former. ECT has been reported to be effective in NMS,34 but intensive supportive medical treatment, discontinuation of neuroleptic therapy, use of dantrolene, and use of bromocriptine are still the essential steps of management.

RISK FACTORS

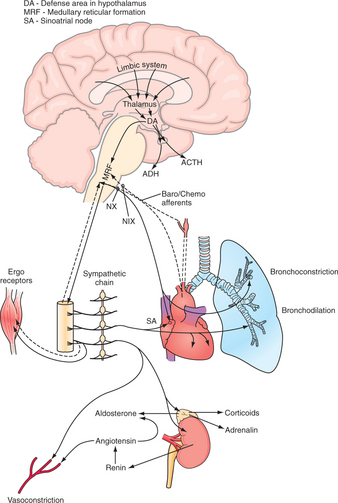

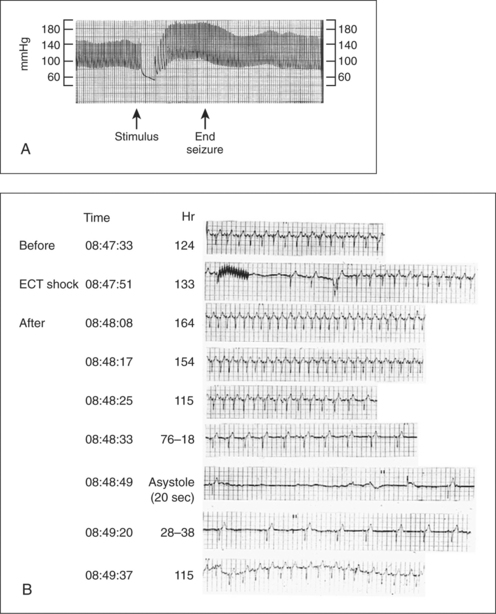

The heart is physiologically stressed during ECT.35 Cardiac work increases abruptly at the onset of the seizure initially because of sympathetic outflow from the diencephalon, through the spinal sympathetic tract, to the heart (Figure 45-1). This outflow persists for the duration of the seizure and is augmented by a rise in circulating catecholamine levels that peak about 3 minutes after the onset of seizure activity (Figure 45-2, A).36,37 After the seizure ends, parasympathetic tone remains strong, often causing transient bradycardia and hypotension, with a return to baseline function in 5 to 10 minutes (Figure 45-2, B).

The cardiac conditions that most often worsen under this autonomic stimulus are ischemic heart disease, hypertension, congestive heart failure (CHF), and cardiac arrhythmia. These conditions, if properly managed, have proved to be surprisingly tolerant to ECT. The idea that general anesthesia is contraindicated within 6 months of a myocardial infarction (MI) has acquired a certain sanctity, which is surprising considering the ambiguity of the original data.38 A more rational approach involves careful assessment of the cardiac reserve, a reserve that is needed as cardiac work increases during ECT.39 Vascular aneurysms should be repaired before ECT if possible, but in practice, they have proved surprisingly durable during treatment.40,41 Critical aortic stenosis should be surgically corrected before ECT to avoid ventricular overload during the seizure. Patients with cardiac pacemakers generally tolerate ECT uneventfully, although proper pacer function should be ascertained before treatment. Implantable cardioverter defibrillators should be converted from demand mode to fixed mode by placing a magnet over the device during ECT.42 Patients with compensated CHF generally tolerate ECT well, although a transient decompensation into pulmonary edema for 5 to 10 minutes may occur in patients with a baseline ejection fraction below 20%. It is unclear whether the underlying cause is a neurogenic stimulus to the lung parenchyma or a reduction in cardiac output because of increased heart rate and blood pressure.

The brain is also physiologically stressed during ECT. Cerebral oxygen consumption approximately doubles, and cerebral blood flow increases several-fold. Increases in intracranial pressure and the permeability of the blood-brain barrier also develop. These acute changes may increase the risk of ECT in patients with a variety of neurological conditions.43

Space-occupying brain lesions were previously considered an absolute contraindication to ECT, and earlier case reports described clinical deterioration when ECT was given to patients with brain tumors.44 However, more recent reports indicate that with careful management patients with brain tumors or chronic subdural hematomas may be safely treated.45–48 Recent cerebral infarction probably represents the most common intracranial risk factor. Case reports of ECT after recent cerebral infarction indicate that the complication rate is low,43 and consequently ECT is often the treatment of choice for post-stroke depression.49 The interval between infarction and time of ECT should be determined by the urgency of treatment for depression.

ECT has been safe and efficacious in patients with hydrocephalus, arteriovenous malformations, cerebral hemorrhage, multiple sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Huntington’s disease, and mental retardation. Patients with depression and Parkinson’s disease experience improvement of both disorders with ECT, and Parkinson’s disease alone may constitute an indication for ECT.50 Depressed patients with preexisting dementia are likely to develop especially severe cognitive deficits secondary to ECT, but most return to their baseline after treatment, and many actually improve.51,52

The pregnant mother who is severely depressed may require ECT to prevent malnutrition or suicide. Although reports of ECT during pregnancy are reassuring,53 fetal monitoring is recommended during treatment. The fetus may be protected from the physiological stress of ECT by nature of its lack of direct neuronal connection to the maternal diencephalon, which spares it the intense autonomic stimulus experienced by maternal end-organs during ictus.

TECHNIQUE

The routine pre-ECT workup usually includes a thorough medical history and physical examination, with a chest film; electrocardiogram (ECG); urinalysis; complete blood count; and determination of blood glucose, blood urea nitrogen, and electrolytes. Additional studies may be necessary, at the clinician’s discretion. In patients with cognitive deficits, it is sometimes difficult to decide whether a CNS workup is indicated because depression itself is usually the cause of this deficit. A metabolic screen, a computed tomography (CT) scan, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are often useful to rule out causes of impaired cognition unrelated to depression. Whenever a question of primary dementia arises, neurological consultation should be requested. Neuropsychological testing may be diagnostically helpful in making the distinction between primary dementia and depressive pseudomentia.54,55

Antidepressant medications do not necessarily have to be discontinued before ECT, since there is little evidence of a harmful interaction. Indeed, there is preliminary evidence that neuroleptics, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and mirtazapine are not only safe to prescribe during a course of ECT, but also may enhance the therapeutic effectiveness of the treatment.56 Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) may be safely given during a course of ECT, as long as sympathomimetic drugs are not administered.57 Early case reports described excessive cognitive disturbance and prolonged apnea in a small percent of patients receiving lithium during ECT, but more recent data indicate that this is a rare complication, and that concurrent administration of lithium is usually safe.58 Benzodiazepines are antagonistic to the ictal process and should be discontinued.59 Even short-acting benzodiazepines may have a long half-life in a sick, elderly person and make effective treatment less likely. For sedation, patients receiving ECT usually do well with a sedating atypical antipsychotic, such as quetiapine (Seroquel), or a non-benzodiazepine hypnotic, such as hydroxyzine (Vistaril). Anticonvulsants, prescribed as mood stabilizers, are usually discontinued before ECT, but in a recent series of bipolar patients the concurrent administration of lamotrigine did not interfere with treatment, and facilitated transition to maintenance pharmacotherapy.60

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree