CHAPTER 51 Side Effects of Psychotropic Medications

OVERVIEW

Determining which medication is causing a specific side effect, and whether any medication is to blame for a given adverse effect, can be difficult. For example, more than half of all patients with untreated melancholic depression report headache, constipation, and sedation; these same symptoms are frequently attributed to side effects of antidepressant medications.1 A stepwise approach to the assessment of a potential side effect can help to ensure that true side effects are quickly addressed, while knee-jerk reactions that result in the discontinuation of well-tolerated treatments can be avoided. This approach (Table 51-1) involves an assessment of the nature and severity of the effect, a thoughtful investigation into the causality of the effect, and the appropriate management of the symptom.

Table 51-1 A Systematic Approach to Medication Side Effects

| Nature of the Side Effect |

What exactly are the signs and symptoms? In some cases (e.g., drug rash) this can be easily ascertained, while in others (e.g., a severely demented patient with worsening agitation, possibly consistent with akathisia, restlessness, constipation) it may be difficult. |

| Severity of the Side Effect |

| Causality of the Side Effect |

Have there been other changes in medication, medical issues, diet, environment, or psychiatric symptoms? |

| Management of the Side Effect |

| If it appears that a specific medication is causing the side effect, options for management include the following: |

ANTIDEPRESSANTS

Tricyclic Antidepressants

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) have a number of common side effects that require careful management. Anticholinergic effects (including dry mouth, blurry vision, urinary hesitancy, constipation, tachycardia, and delirium) that result from the blockade of muscarinic cholinergic receptors can occur with use of TCAs. In addition, anticholinergic effects can also be dangerous to patients with preexisting glaucoma (leading to acute angle-closure glaucoma), benign prostatic hypertrophy (leading to acute urinary retention), and dementia (leading to acute confusional states). TCAs can also cause sedation that results from blockade of H1 histamine receptors, and orthostatic hypotension, due to blockade of α1 receptors on blood vessels. All three of these side-effect clusters are more common with tertiary amine TCAs (e.g., amitriptyline, doxepin, clomipramine, and imipramine) than with secondary amine TCAs (e.g., nortriptyline, desipramine, and protriptyline). TCAs may also cause increased sweating. Longer-term side effects of TCAs include weight gain (related to histamine receptor blockade) and sexual dysfunction. Table 51-2 describes the management of common side effects of TCAs and other antidepressants.

Table 51-2 Management of Antidepressant Side Effects

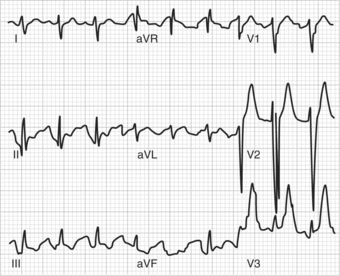

In addition to these common initial and long-term side effects, TCAs may have more serious but uncommon side effects; many of them are cardiac in nature. These agents are structurally similar to class I antiarrhythmics that are actually proarrhythmic in roughly 10% of the population; approximately 20% of patients with preexisting conduction disturbances have cardiac complications while taking TCAs.2 TCAs are associated with cardiac conduction disturbances and can lead to prolongation of the PR, QRS, and QT intervals on the electrocardiogram (ECG) and have been associated with all manner of heart block. These cardiac disturbances can lead to ventricular arrhythmias and to death; while electrocardiographic abnormalities are most commonly seen with overdoses, they can occur at therapeutic doses, especially in those patients with cardiac disease or in those who are on other agents (e.g., quinidine) that are associated with prolongation of cardiac intervals. Some have suggested that effects on cardiac conduction are most severe with desipramine. Furthermore, these agents have been associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction (MI) when compared to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)3; it remains unclear whether SSRIs reduce a depression-mediated increase in MI risk or whether TCAs actually worsen the risk of MI associated with depression. In addition to cardiac effects, other serious adverse events include the serotonin syndrome that occurs most often when TCAs are combined with other serotonergic agents, especially monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). This syndrome can include confusion, agitation, and neuromuscular excitability (including seizures), and is more comprehensively discussed in Chapter 55.

Adverse effects associated with TCA overdose include the exacerbation of standard side effects (e.g., severe sedation, hypotension, and anticholinergic delirium). Ventricular arrhythmias and seizures can also result from TCA overdose. TCA overdose is frequently lethal, with death most often occurring via cardiovascular effects. Figure 51-1 shows an ECG (with characteristic QRS interval widening) of a patient following TCA overdose.4 A withdrawal syndrome (manifested by malaise, nausea, muscle aches, chills, diaphoresis, and anxiety) can occur following abrupt discontinuation of TCAs; the syndrome is thought to result from cholinergic rebound.

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are generally well tolerated; however, they still are associated with a number of side effects. The most common side effects of SSRIs include gastrointestinal side effects (e.g., nausea, diarrhea, and heartburn) that likely result from interactions with serotonin receptors ([primarily 5-HT3] that line the gut), central nervous system (CNS) activation (e.g., anxiety, restlessness, tremor, and insomnia), and sedation that appear within the first few days of treatment. Gastrointestinal side effects may be most common with sertraline and fluvoxamine, CNS activation with fluoxetine, and sedation with paroxetine. Headache and dizziness can also occur early in treatment. These symptoms often improve or resolve within the first few weeks of treatment. Rarely, akathisia or other extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) may occur (sertraline appears to be the most frequent offender due to its dopamine-blocking properties). Nausea, insomnia, and somnolence are adverse effects that most often account for discontinuation of SSRIs. It is notable that the rate of discontinuation due to side effects is higher with fluvoxamine than with other SSRIs.

Longer-term side effects associated with SSRIs include sexual dysfunction, which occurs in 30% or more of SSRI-treated patients; SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction occurs in both men and women, affecting both libido and orgasms. Weight gain, fatigue, and apathy are infrequent long-term side effects; weight gain may occur more frequently with paroxetine. The syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH) can occur with all SSRIs, though it may be more frequent with fluoxetine.5 Finally, SSRIs may increase the risk of bleeding, primarily due to the effects of these agents on serotonin receptors of platelets, resulting in decreased platelet activation and aggregation; it appears that the bleeding risk associated with use of SSRIs is similar to that of low-dose nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents (more than 120 cases have already been reported).6 SSRIs do not, in general, cause cardiovascular side effects, and they are relatively safe in overdose. The serotonin syndrome can occur when these agents are combined with other serotonergic compounds, or, very rarely, when used alone.

Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors

Venlafaxine

Venlafaxine’s initial side effects are similar to those of the SSRIs. Nausea and CNS activation appear to occur somewhat more commonly than with the SSRIs; in addition, dry mouth and constipation may be associated with venlafaxine use despite lack of effects on muscarinic cholinergic receptors. Increased blood pressure, presumably related to effects on norepinephrine, can occur with immediate-release venlafaxine, with 7% of patients taking 300 mg per day or less and 13% taking doses greater than 300 mg having elevation of blood pressure; this resolves spontaneously in approximately one-half of cases.7 The extended-release (XR) formulation appears to be associated with lower rates of hypertension. Sexual dysfunction occurs at approximately the same rate as occurs with SSRIs. Aside from effects on blood pressure, venlafaxine does not appear to have substantial adverse effects on the cardiovascular system. Among more serious side effects, SIADH and serotonin syndrome have been reported with venlafaxine.

Overdose of venlafaxine generally causes symptoms similar to those of SSRI overdose. However, venlafaxine, according to one large epidemiological study in the United Kingdom,8 has been associated with a high rate of death in overdose (possibly via seizure and cardiovascular effects); other (smaller) studies have not found an increased lethality with overdose. Finally, due to the short half-life of venlafaxine, the discontinuation syndrome reported with SSRIs is common in patients who abruptly stop taking this antidepressant.9

Duloxetine

In general, duloxetine’s common side effects are similar to those of SSRIs. Nausea, dizziness, headache, and insomnia may be somewhat more frequent than with SSRIs, but overall this agent is well tolerated.10 Duloxetine does not have significant effects on blood pressure or other cardiovascular parameters. Sexual dysfunction appears in concert with duloxetine use, but rates of sexual dysfunction may be less than those associated with paroxetine.11 Duloxetine has not shown significant affinity for histaminic or cholinergic receptors, and thus sedation, weight gain, and anticholinergic effects are uncommon.

With respect to more severe adverse effects, SIADH has been reported with duloxetine use,12 and serotonin syndrome may develop with this agent because of its significant serotonin reuptake inhibition. Increased levels of hepatic transaminases develop in a small percentage of patients taking duloxetine; this is usually asymptomatic, but patients with chronic liver disease or cirrhosis have experienced elevated bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, and transaminases, and currently it is recommended that duloxetine should not be given to patients who consume substantial amounts of alcohol or who exhibit evidence of chronic liver disease.13 Duloxetine does not appear to have increased rates of death in cases of overdose. A discontinuation syndrome similar to that seen with SSRIs and venlafaxine can occur with abrupt withdrawal of duloxetine,14 though it is probably less likely than with venlafaxine or paroxetine due to its longer half-life.

Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors

Hyperadrenergic crises, characterized by occipital headache, nausea, vomiting, diaphoresis, tachycardia, and severe hypertension, can occur in patients taking MAOIs. These most commonly occur when tyramine-containing foods are consumed or when adrenergic agonists (such as sympathomimetics) are taken in combination with MAOIs. Table 51-3 lists tyramine-containing foods that should be avoided by patients on MAOIs.15 Serotonin syndrome can also occur with MAOIs when these agents are taken with SSRIs, TCAs, or other serotonergic agents (Table 51-4 lists medications that should be avoided by patients taking MAOIs). MAOI overdose is quite dangerous, with rates of death higher than those for SSRIs and other newer antidepressants,8 with serotonin syndrome, neuromuscular excitability, seizures, arrhythmias, and cardiovascular collapse all possible.

Table 51-3 Foods to Be Avoided by Patients Taking Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors

| All matured or aged cheeses (fresh cottage, cream, ricotta, and processed cheese are tolerated) Pizza, lasagna, and other foods made with cheese Fermented/dried meat (e.g., pepperoni, salami, or summer sausage) Improperly stored meat and fish Fava or broad bean pods Banana peel (banana and other fruit are tolerated, but do not use more than ¼ pound of raspberries) All tap beer (two or less cans/bottles of beer or 4 oz glasses of wine per day) Sauerkraut Soy sauce and other soybean products (soy milk is acceptable) Marmite yeast extract (other yeast extract are acceptable) |

Data from Gardner DM, Shulman KI, Walker SE, et al: The making of a user friendly MAOI diet, J Clin Psychiatry 57:99-104, 1996.

Table 51-4 Medications to Be Avoided by Patients Taking Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors

| Increased Risk of Serotonin Syndrome |

| SSRIs TCAs Mirtazapine Nefazodone Lithium Dextromethorphan Tramadol Carbamazepine Sumatriptan and related compounds Cocaine MDMA St. John’s wort SAMe |

| Increased Risk of Hyperadrenergic Crisis |

| Dopamine L-dopa Psychostimulants Bupropion Amphetamine Cold remedies or weight loss products containing pseudoephedrine, phenylpropanolamine, phenylephrine, or ephedrine |

| Other |

| Meperidine (may cause seizures and delirium) |

MDMA, 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylamphetamine; SAMe, S-adenosyl-methionine; SSRIs, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; TCAs, tricyclic antidepressants.

Finally, the new transdermal MAOI (selegiline) patch is worth mentioning; this patch does not require dietary modification at its lowest dose. At this lowest dose (6 mg/24 hours) transdermal selegiline appears to have an incidence of orthostatic hypotension, gastrointestinal side effects, weight gain, and sexual dysfunction that is greater than placebo, but lower than with orally ingested MAOIs; skin irritation at the patch sites has been the most common adverse effect. However, this agent is still relatively new, and further information about associated adverse effects will come with greater experience.

Other Antidepressants

Trazodone

Trazodone is associated with significant sedation. Other common initial side effects can include dry mouth, nausea, and dizziness; orthostasis is much more common than with nefazodone, with reports of syncope.16 As with nefazodone, weight gain and sexual dysfunction are rare, and, unlike nefazodone, trazodone does not appear to be associated with increased hepatotoxicity. Trazodone has, very infrequently, been associated with cardiac arrhythmias,17 possibly due to effects on potassium channels, and it should be used with caution in patients with a propensity for, or history of, arrhythmias. Priapism occurs in approximately 1 in 6,000 male patients who take trazodone; this effect usually occurs within the first month of treatment.18 In overdose, sedation and hypotension are the most common adverse effects; isolated trazodone overdose is rarely fatal. There is no discontinuation syndrome.

MOOD STABILIZERS (LITHIUM AND ANTICONVULSANTS)

Lithium

Lithium has many associated adverse effects, summarized in Table 51-5. Gastrointestinal and neurological side effects (e.g., sedation and tremor), along with increased thirst, often occur early in therapy, while effects on thyroid and renal function occur more chronically. Table 51-6 summarizes potential treatments for lithium side effects; change in dosing and formulation can reduce gastrointestinal side effects, while other side effects require additional therapies. Lithium has some effects on sinoatrial node transmission and (less commonly) atrioventricular conduction. However, it has not been commonly associated with other effects on the cardiovascular system, and cardiac disease (aside from sick sinus syndrome) is not an absolute contraindication for lithium use. Lithium has a low therapeutic index and lithium toxicity (whether intentional or unintentional) can lead to a variety of symptoms, including neurological (e.g., severe sedation, tremor, dysarthria, delirium, anterograde amnesia, myoclonus, and seizure), gastrointestinal (e.g., nausea and vomiting), and cardiovascular (e.g., arrhythmia) effects; renal function often is impaired, and dialysis may be required to treat lithium toxicity if supportive measures and intravenous normal saline to aid lithium excretion are ineffective. Lithium does not have a characteristic discontinuation syndrome, but rapid withdrawal of lithium therapy is associated with substantially higher rates of relapse than when lithium is tapered.19

Table 51-5 Common Adverse Effects of Lithium

| Neurological |

| Sedation Tremor (fine action tremor) Ataxia/incoordination Cognitive slowing |