Module 6: Documentation of PCCP: Writing the plan to honor the person AND satisfy the chart

Goal

This module details how to reflect person-centered principles and practices in the documentation of the written recovery plan. Strategies are presented for maximizing the recovery orientation of the plan and meeting the rigorous documentation expectations of fiscal and accrediting bodies.

Learning Objectives

After completing this module, you will be better able to:

- define the key documentation components (i.e., goals, objectives, and interventions) of the person-centered care planning (PCCP) as a roadmap to recovery and wellness;

- note two ways in which PCCP documentation differs from the traditional written treatment plans;

- write meaningful short-term objectives that reflect the S-M-A-R-T criteria;

- create and record rigorous person-centered care plans that support the individual’s recovery while meeting regulatory and payer requirements.

Learning Assessment

A learning assessment is included at the end of the module. If you are already familiar with this subject, you may want to go to the end of this module and take the assessment to see how much you know already. Then you can focus your learning efforts on what is new for you.

Introduction to the Documentation of Person-Centered Care Plans

As previously stated, person-centered care planning (PCCP) consists of four components: philosophy, process, plan, and product. We have previously discussed philosophy and process, and this module focuses on this third “P” of documenting the written care plan. Specifically, we address a question that is frequently posed by practitioners working on PCCP: Is it possible to write a plan that honors the person while still satisfying the chart, my supervisor, our funders, and so on? This documentation section is included in recognition of the fact that many highly skilled practitioners embrace both the philosophy and the process of PCCP and yet struggle to reflect this in the context of the written planning document. Frequently, it is in this step of moving from “process” to “plan” that the quality of PCCP breaks down and the written document devolves into one that is both deficit-oriented and professionally driven rather than staying true to the principles of PCCP.

But, first, you might be wondering: “Does it really matter? The written plan is NOT something that is a meaningful part of the work… In fact, it gets in the way of the work!” If this is on your mind, you have lots of company! Frequently, the written plan is viewed simply as a technical document that has to be completed to satisfy accrediting or reimbursement bodies, and is seen as useful neither to the practitioner nor to the person receiving care. In such cases, the plan is completed and filed in the medical record and it plays a little, if any, role in actually guiding the work of the team moving forward. While this may be a widely held perception of care planning documentation, in the person-centered world, the plan of care has the potential and should be far more than a paperwork requirement. It is a written contract between a person and his or her network of supporters that outlines a more hopeful vision for the future and how all will work together to achieve it. The pivotal role of the service plan in transforming systems of mental health care was perhaps best described in the US President’s New Freedom Commission Report [1], which noted that customized plans should be developed in full partnership with consumers as “the plan of care is at the core of the consumer-centered, recovery oriented system.”

The plan of care has the potential, and should be, far more than a paperwork requirement …

Given the centrality of the PCCP in driving system change, it is imperative that practitioners increase their competency in creating collaboratively developed documents that “honor the person while also satisfying the chart.” But for many practitioners, developing these skills may take practice if they differ significantly from their typical style of care planning documentation. This section is therefore intended to support practitioners in the practical implementation of PCCP by presenting a general overview of the core documentation elements along with tips for maximizing the person-centered aspects of each. It is not intended to substitute for the rich discussion of philosophy and process that has preceded this module, as the quality of the planning document is only as good as the values and partnership on which it is based. Put simply, all four “Ps” need to come together for the vision of PCCP to become a reality. In addition, this module is not intended to be a “compliance” guide for meeting specific care planning documentation requirements. These requirements vary widely across states, counties, and particular programs, and, as such, a discussion of these is beyond the scope of this module. Here we focus more on the larger question of “quality” rather than the specific requirements of “compliance.”

Medical Necessity and Documentation of the PCCP

Medical necessity refers to the expectation that services are provided to impact a diagnosed condition that is causing symptoms, distress, and/or functional impairment, and that is likely to improve as a result of the proposed treatment or intervention. Typically, services are paid for under an insurance plan only if they meet the criteria for medical necessity. In many settings, medical necessity also establishes a standard of service and quality of care. One aspect of quality care is about doing the right thing, at the right time, for the right reason. While a care plan can include many options (including action steps taken by the person in recovery as well as any natural supporters who may be involved), practitioners will be paid by insurance programs only for those services that meet medical necessity criteria, that is, the rationale for providing the service is clear as it relates to helping the person to overcome clearly documented mental health-related impairments that are negatively impacting his or her life and functioning. It is important to note that the interventions do not have to reduce or eliminate the condition altogether to be considered medically necessary. Rather, interventions may be considered necessary if they are required by the nature of the person’s condition in order for him or her to be able to live the meaningful and dignified life of his or her choice.

Because of this required link back to mental health symptoms or impairments, many practitioners believe that the construct of “medical necessity” is wholly incompatible with the goal-oriented, strength-based nature of person-centered care plans. Some have described it as feeling “caught between a rock and a hard place.” On the one hand, they must write a plan that honors the person’s valued goals, strengths, and priorities. On the other hand, that same plan needs to meet a whole host of external requirements set forth by regulatory bodies and funders.

It is the reality of the current mental health system that the requirements of primary payers such as Medicare and Medicaid are difficult to balance in the context of creating person-centered care plans. However, practitioners are encouraged to learn about their state’s Medicaid plan(s) in detail prior to making an assumption that meeting medical necessity criteria is an insurmountable challenge. More information and understanding of the real and perceived barriers to doing PCCP is needed, as there have been developments in recent years that have widened the scope of reimbursable services (such as those provided under the Rehabilitation Option) and established new funding mechanisms (such as self-directed budgeting pilots).

In addition, contrary to common myths in the field, the documentation of PCCP need not be “soft” in any way. In fact, emerging practice guidelines explicitly call for the documentation of (i) comprehensive clinical formulations, (ii) mental health-related barriers that interfere with functioning, (iii) strengths and resources, (iv) short-term, measurable objectives, and (v) clearly articulated interventions that spell out who is doing what on which timeline and for what purpose [2] [3]. We suggest that these standards for PCCP documentation are on par with, if not superior to, the level of rigor that actually exists in most clinical and rehabilitation plans around the country, and believe that the documentation tips provided below support, rather than undermine, compliance with regulatory requirements. Medical necessity and person-centered care are not incompatible constructs, and service plans can be created in partnership with persons in recovery while also maintaining rigorous standards around treatment and documentation.

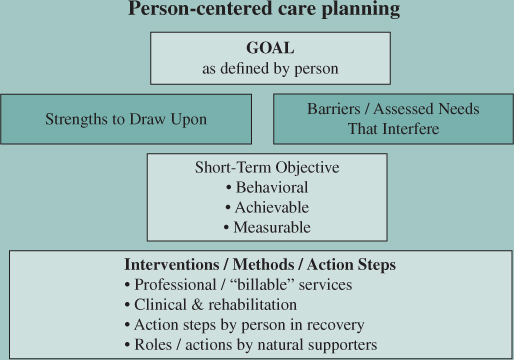

While plans can be quite elaborate and detailed, a person-centered care plan contains several core elements that are depicted in Figure 6.1 and described in greater detail in this module.

Figure 6.1 Core Elements in a Person-Centered Care Plan

Many people find that the terms presented in Figure 6.1 are not entirely intuitive and have difficulty in differentiating each of the elements. It is important that early on, in learning about PCCP, there is a clear understanding of these essential, and distinct, documentation components.

Goals

The creation of the PCCP document should flow from goal statements that reflect what the person receiving services would like to achieve in his or her life. Goals are decided following a thorough strength-based assessment as described in Module 4 and through a collaborative dialogue (see Module 5) with the person receiving services and his or her team. The key elements of goal(s) within a person-centered care plan are described below:

Goals: Important to the Person

A well-written goal statement on a PCCP reflects that which is important to the focus person rather than that which historically has been given priority in the professional service system.

Ideally, the goal is expressed in the person’s own words and is based on his or her unique interests, preferences, and strengths. A goal is a statement of something important for an individual to achieve in his or her personal recovery. It may be a life goal, a treatment goal, or a goal to improve the quality of the person’s life. This approach to a goal statement can be quite different from the manner in which goals are typically documented in professionally driven service plans. Traditionally, goals are focused more narrowly on the amelioration of symptoms or deficits associated with the mental health condition (e.g., behaviors, functional limitations) thereby losing the focus on personally valued and meaningful life goals. Goals, for example, to remain medication compliant, reduce behavioral outbursts, maintain stability, and increase insight are commonly listed on service plans despite the fact that persons in recovery rarely see these things as meaningful or motivating long-term outcomes. This is not to say that these things are necessarily negative or undesirable. But, reducing symptoms, increasing compliance, and staying out of the hospital are means to an end and they do not, in and of themselves, equate with the realization of a person’s ultimate vision for his or her future.

If of thy mortal goods thou art bereft,

And from thy slender store

Two loaves alone to thee are left,

Sell one, and with the dole

Buy hyacinths to feed thy soul.

— Sa’adi [4]

Therefore, in supporting individuals to either develop or modify their PCCP goals, it is important for practitioners to keep in mind that the goals of the plan should not be limited to clinically valued or professionally determined outcomes. Rather, goals should be defined by the person with a focus on attaining the life he or she envisions for himself or herself in the community. A well-written goal statement on a PCCP reflects that which is important to the focus person rather than that which historically has been given priority in the professional service system.

“How would your life look different if [this problem] were gone?”

Ideally, such goals are written in positive language, remembering that this is an opportunity to embody and reinforce hope and growth. A goal is best thought of as something to move toward rather than something to get rid of. For example, in working with individuals to identify a recovery goal for their care plan, it is not uncommon for people to stick to the territory they are most accustomed to exploring with treatment teams. You may hear, “I just want to be less depressed,” or even, “I want the voices to quiet down.” Rather than accepting this as the final goal for the plan, a skilled practitioner will go deeper and ask the individual, “If you were less depressed, or if the voices were quiet, can you tell me how your life would be different? What would you be doing every day? What kinds of things might you enjoy? What would be different?” Most often, this type of inquiry in the goal-setting process will generate PCCP goal statements that focus on the following types of areas:

- Managing own life – I want to control my own money.

- Work/education – I want to finish school.

- Spiritual issues – I want to get back to church.

- Satisfying relationships – I want to see my grandkids.

- Adequate housing – I want to move out of the group home.

- Social activities – I want to join a bowling league.

- Health/well-being – I want to lose weight.

Goals: A Manageable Number

Sometimes people articulate multiple goals, sometimes none at all. Each scenario presents different challenges.

Too many goals?

In this case, it is most effective to help the person to prioritize and identify just a few key goal areas on the plan. Having too many goals can make the plan complicated and unwieldy—both for the practitioner to write and, most importantly, for the person to actually “work” out that plan in his or her daily life! In order for the plan to be a truly effective tool in guiding recovery, it is helpful to limit the goal statements to those that are most salient and motivating to the individual at that point in time. Often, the most powerful and effective plans are focused only on one larger goal. This does not mean that the person does not have goals or challenges in other areas that might ultimately need to be addressed, but it can be helpful to give dedicated attention to a specific area over a defined time frame while deferring other goals to a future plan.

An important reminder: As discussed in Module 4, take care in the goal-setting and prioritization process; do not “table” what is most important to the person, including only that which you think is important for them from a clinical or professional perspective.

No goals?

How about the alternative scenario? Practitioners often ask: What do I do if the person has NO goals or if he or she is content with the way things are? First, remember that most people do not live their lives explicitly in terms of “goals,” and the person may not be accustomed to being asked about life goals beyond those usually identified in treatment. Previous experiences of care planning may have involved limited participation; perhaps the person was only expected to lend a signature after the written document had been created. This highlights the shift in roles and responsibilities that occurs in PCCP, and underscores the importance of the preplanning steps detailed in Module 2. If PCCP is about getting the person in the “driver’s seat” to the maximum extent possible, then some people will benefit from “driver’s education” so they can be fully prepared to partner with their team from start to finish.

The practitioner and other team members, including peer specialists, play an important role in this process by maintaining a positive attitude and focusing on the possibilities for the future rather than the challenges. Put simply, practitioners may need to be “holders of hope” in situations in which the focus person is having difficulty expressing goals or a more positive vision for the future. A spirit of hope is communicated in attitude as well as through the specific tools she or he uses throughout the PCCP process. For example, it is essential that practitioners be skilled in the use of strength-based assessment and motivational enhancement techniques as these can be particularly helpful in supporting individuals to rediscover (or discover for the first time!) goals and dreams that they may have lost along the way.

In this way, being person-centered does not mean refraining from offering suggestions or ideas when a person is stuck about what they would like to work on. Ideas may emerge at any time during conversations or sessions, and these might be revisited around the time of planning. Here is an example: one of us, while assisting in preparing a plan with someone receiving services, asked: “Do you have any goals you’d like to work on?” and received a resounding and desultory “no” for the answer. Yet when asked if the person was interested in working, the person answered in the affirmative and offered several job ideas. Entering into the conversation from a “side door” rather than head-on can be helpful, as can suggestions and reminders of previously mentioned interests and goals from prior conversations. Important to stress, though, is continuing to utilize strong clinical skills and judgment in determining whether a friendly suggestion is being taken instead as a command or dictum. Awareness of power and authority is essential in the PCCP goal setting process just as it is in any productive therapeutic practice or relationship.

Goals: Time Framed?

Goals may be set for a shorter or longer period of time. Depending on the funder requirements and the regulations of your state and agency, time frames for goal statements may, or may not, need to be specified on the recovery plan. The important thing to remember is that the scope of goal statements should vary depending on an individual’s personal preferences and current priorities. The goal may be 5 years down the road, or something that may be accomplished in the next 6 months. For example, a person may prefer, and be highly motivated, to set an ambitious long-term goal such as “Graduating from college,” which may take several years to accomplish. Another individual may feel overwhelmed at the scope of such a task, and might prefer to start with a goal of “Completing a class at the local Adult Education Department,” which may be achieved within a much shorter period of time.

Goals: Attainable and Realistic?

Ideally, the identified goal is attainable and realistic for the individual—but there may be times when there is disagreement on this issue. Whether or not a practitioner views a given person’s goal as feasible need not become a source of conflict or disagreement or a barrier to developing the plan. For example, if a practitioner is concerned that a person’s stated goal is unrealistic, this goal might be preserved out of respect for the individual’s preferences and understanding of his or her own recovery. Practitioners cannot predict the future, and should not presume to do so. In fact, many people currently working as peer staff within the mental health system report being told by practitioners earlier in their recovery that they would never be able to return to work because of the severity of their illness. Such pronouncements are not only demoralizing, but also convey a sense of certainty that is simply not warranted by the available data.

When crafting the goal statements for the service plan, it is far more helpful for the practitioner to help the person to THINK BIG as this is an opportunity to demonstrate faith and hope in their recovery process. A word of caution NOT to become overly concerned with whether or not the goal statement is “realistic” as determining what is realistic (or not) is a slippery slope and often allows unspoken biases or assumptions to come into play. There will be places later in the care planning document (most notably the short-term objectives discussed later in this module) to carve out smaller “achievable” first steps but, for the purpose of the goal statement, it is most helpful to retain the long-term goal that is most motivating for the individual. During the initial goal-setting process, the practitioner and/or peer specialist should therefore remind all team members to refrain from making comments that reflect skepticism or doubt regarding the feasibility of the long-term recovery vision.

There are times when the practitioner will have a different sense of priority goals and is often inclined—by virtue of training, experience, and even at times legal obligations or mandates. In most cases, practitioners view basic health and safety needs for food, clothing, shelter, and medical care, if indicated, as a first priority. On the other hand, a not uncommon point of difference is when co-occurring drug or alcohol use confounds the picture. In these circumstances, a harm reduction strategy might be a reasonable approach. Regardless, some recognition of the differences and negotiation to a point of shared priorities is essential if the rest of the PCCP process is to succeed. Consider the following example.

A man who was receiving services in a mental health program had the misfortune of having three different mental health providers in one year. The first provider met with the man to do a treatment plan with him. The provider asked the man: “What are your goals?” The man responded: “Well, I really want to be an astronaut!” The provider attributed the statement to the man’s ongoing delusions; believed that other things were a bigger priority; and was concerned that to allow such a goal would be “setting him up” for failure. The provider suggested he needed to focus on finding a new place to live because his lease was up. “First things first,” he said as he wrote the housing goal in the plan. Even after the man had secured an apartment, there was no further follow-up about the man’s interest in becoming an astronaut.

Six months later, it was time for the man’s review and he met a new provider. This provider sat with the man, looked over the plan, and asked: “What are your goals?” Once again, the man responded: “I really want to be an astronaut!!” The provider, who made little eye contact with the man while he wrote furiously on the document, responded that he had been to the man’s apartment and felt that he really needed to work on his ADL (activities of daily living) skills. The provider wrote this on the review, and tabled the man’s goal of being an astronaut as unrealistic – a grandiose idea that did not warrant further exploration.

Six months later … new review … new provider. By this time, the man had just about given up. The new provider sat down with the man and asked him: “What are your goals?” The man, knowing what he really wanted, responded: “I REALLY want to be an astronaut!!!” This provider looked directly at the man and said: “Okay, here’s the deal. Go to the library. Get all of the information you can about what you will need to do to be an astronaut and I will do some research too. Bring the information back in two weeks and we’ll discuss it together.” The man left encouraged for the first time in a long time.

Two weeks later, the man came back and plopped a sheaf of papers on the desk of the provider and declared: “I can’t possibly do all of this! I need to have a Ph.D. in physics, be an officer in the military, go through all of these tests and physicals … this is too much!” The provider smiled inwardly, but did not blink an eye as he said: “Okay, don’t give up yet. What were the things about being an astronaut that most appealed to you? What about it gets you excited?” Over the next several sessions, they worked on the things that the man could do to realize certain parts of the dream.

Fortunately, the man and his provider were located in Houston, Texas, very close to the Kennedy Space Center. The provider helped the man to meet people in different capacities there and eventually the man did get a job. While working, the man met a pilot who gave skydiving lessons on the weekends. He tried it and loved it. In skydiving, the man found much of the same freedom and adventure he had sought in his dream of being an astronaut.

Story provided by Sade Ali, Advisory Board Member, SAMHSA Person-Directed Planning Initiative

This story illustrates the importance of “listening” to and understanding people’s priorities as you work together to establish goals for the person-centered plan. Imagine the impact on the helping relationship when this man was repeatedly dismissed and told that his dream of becoming an astronaut needed to take a backseat to the goals that each of his providers deemed important. While it is true that providers often have an obligation to help ensure that an individual’s basic needs (e.g., housing) or clinical needs (e.g., acute symptoms) are addressed, it is essential to balance this with a simultaneous appreciation for needs and goals as expressed by the person. Doing so can lead the individual to discover a whole range of new experiences that serve to further his or her own personal recovery process.

Goals: Something We Get Paid For?

Goals discovered through the PCCP process frequently will involve the types of statements noted earlier in this module, that is, I want to go back to church … have a girlfriend … join a bowling league, and so on. Practitioners and administrators have expressed concern that these written goal statements will not be allowed by internal or external compliance and regulatory bodies, as they are not consistent with their mission to provide a particular professional service, for example, We are in the mental health business and these goals don’t sound very “mental-health-like!” This belief that funders will not pay for nonclinical life goals is actually a correct one, but not because of the nature of the goal itself. Rather, it is the fact that funders do not pay for goals at all. Funders pay practitioners for the interventions and other professional services they provide to help people overcome mental health-related barriers that interfere with their functioning and attainment of valued personal goals. So, for the many PCCP practitioners who, by necessity, must also concern themselves with regulatory compliance and “medical necessity,” keep in mind that there will be places within your plan documentation for you to build this “business case.” However, more so than any other part of the plan, the goal statement truly belongs to the individual and it should honor his or her unique vision for the future.

Goals: A Note on the Stage of Change

It is important to remember that goal statements on a PCCP may look very different depending on a person’s readiness to change and level of engagement in services. Goals focusing on life changes presume a preparatory or action stage of change as well as a belief on the part of the person that mental health services can help him/her to make such a desired change. Some people may still be in the process developing a trusting and working relationship with the practitioner and service agency, so they may have difficulty engaging in active goal setting. The goal in such cases might simply be engagement, and may be something first identified by the practitioner. The goal may also be identified as something like “I want to get mental health practitioners and treatment out of my life,” for those who want to stop receiving services. Even in such cases, developing collaborative goals is often the first step toward building the trust needed for the person to give treatment a chance to make a positive difference in his or her life.

Strengths and Barriers

Once the goal has been identified, the next step in creating a plan is to identify those specific strengths that will support the person in attaining the goal, and those barriers (including mental health and addiction-related barriers) that stand in the way of goal achievement.

Strengths

Focusing solely on deficits and barriers in the absence of a thoughtful analysis of strengths disregards the most critical resources an individual has on which to build in his or her efforts to achieve life goals and dreams. Thus, it is considered a key practice in PCCP to thoughtfully consider the potential strengths and resources of the focus person as well as his or her family, natural support network, and community at large. For this reason, a key role of the practitioner (as discussed in greater detail in Module 4) is to support the individual in identifying a diverse range of strengths, interests, and talents while also considering how to actively use these strengths to pursue goals and objectives in the person-centered care plan. Put simply, all too often strengths are identified in the assessment and preplanning process and yet appear nowhere on the final written document! Strengths are not identified just to “sit on a shelf.”

Rather, the team needs to think creatively about how to explicitly incorporate them in the various activities within the PCCP. For example, if the focus person identifies his or her faith and spirituality as a cornerstone of well-being, are these types of activities reflected in his or her daily personal wellness plan? If the individual has a love of creative writing, is this identified as a positive coping strategy the person can use to manage stress or difficult emotions? If the person is an accomplished musician, might he or she work toward volunteering to teach music lessons to others at the local community or senior center?

This emphasis on individual and/or family “strengths” rather than deficits or problems is sometimes a difficult process for professional service practitioners as well as the service user himself or herself! It is not uncommon, for example, for individuals to have difficulty identifying their “strengths,” as this has not historically been the focus of professional services and assessments. Individuals also may have lost sight of their gifts and talents through years of struggles with their disability and discrimination. As a result, simply asking the question “What are your strengths?” is seldom enough to solicit information regarding resources and capabilities that can be built on in the planning process. Guiding principles and sample questions to be used in strength-based interviewing are provided previously within this document (see Module 4 for a broader discussion and ideas for specific questions in this area).

Barriers

While capitalizing on a person’s strengths, it is also necessary for the “roadblocks” that interfere with goal attainment—often in the shape of disability-related limitations, experiences, or symptoms—to be identified and addressed in the PCCP. Barriers should be acknowledged alongside assets and strengths, as this is essential not only for the purpose of justifying care and the “medical necessity” of the professional services and supports provided, but because a clear understanding of what is getting in the way informs choices of the various professional interventions and natural supports that might then be offered to the individual in the service of his or her recovery. The difference in a person-centered care plan is that the barriers do not become the exclusive and dominant focus of the plan and only take on meaning to the extent that they are interfering with the attainment of larger life goals. For example, the reduction of symptoms is not seen as the only desired outcome (unless the person himself or herself so chooses), but rather is noted as a way of addressing a barrier (in this case, the barrier being symptoms) in order to help the person return to work, finish school, be a better parent, pursue a hobby, and so on.

In identifying barriers, it is important to be specific. For example, at the individual level, the following types of factors might impede goal attainment:

- Intrusive or burdensome symptoms

- Lack of resources

- Need for assistance/supports

- Problems in behavior

- Need for skills development

- Challenges in taking care of oneself and activities of daily living

- Threats to basic health and safety

An Example: The individual’s goal is to someday work with children, preferably in a preschool environment. However, cognitive and social impairments resulting from the effects of a mental health condition have made it difficult for the person to achieve a high school diploma (which is required for most positions in preschool education). A traditional service plan might note that the goal is to “reduce symptoms,” “increase concentration,” or perhaps “decrease paranoia.”

In a PCCP, the goal is stated simply in the person’s own words

I want to get my degree in education and someday be a teacher.

with perhaps a shorter term objective being to receive a GED. The following might then be noted in the barriers section of the plan:

Barriers: difficulty concentrating due to depression; previously unable to meet attendance requirements at GED class due to lack of energy and high anxiety; difficulty remembering, tracking, and completing assignments; at times uncomfortable around and fearful of other students; anxiety related to taking bus to GED classes.

These specific barriers provide targets for interventions to address and justify services through establishing the medical necessity of care.

In addition to exploring these individual-level barriers, it is important to note the extent to which external barriers might also be interfering with goal attainment. For example, many individuals who wish to pursue their education have difficulty securing financial aid, transportation, childcare, or classroom accommodations. A key role of the practitioner is to work with the individual and team to identify both internal and environmental barriers and to determine strategies and solutions that help the person to move forward through, under, over, or around these barriers.

Objectives

Goal statements are useful as they give direction for the overall recovery journey and all that it entails. Just as in pursuing any goal, it is essential to identify specific, shorter term action steps that can help the person to move toward his or her life goals and dreams. These steps are usually referred to as objectives and are best thought of as interim goals that break down longer term aspirations into meaningful and positive short-term changes. For example, in the vignette described, getting a GED was a target objective en route to a longer term goal of working with children.

A strong objective should reflect a concrete change in functioning, in behavior, or in status, that, when achieved, will provide the “proof” that the person is making progress. As much as possible, objectives should describe the development of new skills and abilities, including the ability to access the needed supports and accommodations. For instance, an individual may need to develop an ability to negotiate certain workplace accommodations from his or her employer. This kind of focus on skill building and enhancing self-management goes a long way toward promoting recovery and the person’s vision of the future.

As with all parts of the written PCCP, these objectives should be arrived at only after a thoughtful dialogue with the person about what he or she feels would be a meaningful “step in the right direction.” Practitioners may need to help the individual establish objectives. If the person could do it himself or herself, then he or she most likely wouldn’t be seeking services! Here is where the practitioner’s role as coach, collaborator, and so on is prominent. In addition to assisting the person in identifying feasible and meaningful objectives, the practitioner can then be instrumental in identifying, describing, and eventually offering the services and supports that will be useful to the person as he or she pursues his or her goals.

Objectives: How Ambitious or Modest?

The development of objectives is an area in which the practitioner can make perhaps the most significant contribution toward the person’s recovery. Objectives should be defined as “doable” so that the person can move along toward a stated goal and build on incremental successes. Note that sometimes, the individual needs to try new behaviors that not everyone on the team thinks are “attainable” or “realistic.” If attempting these new activities remains the person’s preference, though, then the team should support that decision. The person may then succeed despite the team’s concerns, or, if it is the case that the person does NOT meet the objective, the lessons learned may be productive and helpful to both the service user and practitioners. This should not be taken as a “failure” but rather an opportunity for the team to reevaluate the plan for possible modification of the objective or even the addition of a new service or support.

When service users are besieged by their problems and see little more than barriers to their goals, the discussion of short-term objectives allows the practitioner to use his or her problem solving skills to build on the individual’s strengths and identify a modest and manageable step that will help move the person forward. Building on the example above, that is, a valued goal to finish school and work with children, let’s assume that a major depression with psychotic features has led to multiple recent hospitalizations, and severe sleep disturbance with the individual sleeping nearly 18 hours a day. The service user may feel overwhelmed in identifying the next steps and this may prevent him/her from taking action, particularly around something as ambitious as completing the GED. This is where we see the benefit of crafting highly individualized objectives that can preserve the valued goal while truly meeting the individual where he or she is at. The individual might start with a simple and modest objective to overcome her sleep disturbance as evidenced by her ability to reestablish a morning routine and be up and out of the house by 9am, 5 days per week over the next 30 days. Assuming the service user agrees that this would feel like a good place for her to start, such an objective moves her closer to her goal of returning to school while also clearly targeting improvement in a mental health barrier (thereby maintaining the link between the assessment and the plan and supporting medical necessity). At the same time, objectives should not be broken down to the point where they become trivial or are seen as condescending by the person served, for example, a man with a Masters Degree in Nursing who is asked to work on an objective to “verbally identify 3 negative health consequences of current diet within 6 months.” Such objectives, while technically correct and easy to write, can reflect a lack of understanding of the person and his true barriers to a healthier lifestyle.

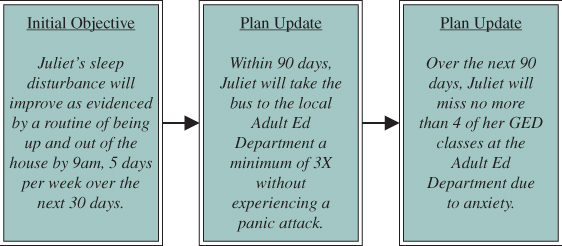

When deciding how ambitious or modest to be in setting the short-term objective, it can be helpful to remember that “progressive” objectives may be written in a sequential manner (as illustrated in Figure 6.2), that is, the achievement of one objective may trigger the activation of another in a future plan update. In this way, by dividing larger goals into smaller actions and benchmarks, objectives can provide hope to both the individual and his or her team by taking what can feel like an overwhelming journey and organizing it in a number of steps in which progress can be made and success celebrated.

Figure 6.2 Sample of a Progressive Objective

Objectives: How Can I Meet All the Technical Criteria?

The writing of objectives (and interventions, to be discussed in the next section) is the most technical part of the entire PCCP documentation process, as these plan elements are closely monitored by funders and accrediting bodies. Supporting individuals to make progress toward meaningful objectives is increasingly expected of services whose mission is to focus on active rehabilitation rather than on maintenance or “clinical stability.” It therefore is important that objectives be accurate and consistent with each of the characteristics noted below.

Beware of the lengthy objectives that use the word ‘and’ – it often means there are multiple objectives rolled into one. This compromises the measurability of the objective. Each objective should be written to reflect a concrete targeted improvement in ONE specific area.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree