Module 7: So you have a person-centered care plan, now what? Plan implementation and quality monitoring

Goal

This module focuses on the processes of documentation follow-up, and continuous quality improvement (CQI) after the plan itself is completed. It outlines the key elements necessary to include in a progress note, the practice of charting to the plan, and using the plan as an everyday part of the direct care work. It also focuses on promoting accountability and ongoing consumer satisfaction with person-centered care planning (PCCP) processes and service outcomes. It is intended to help practitioners, administrators, and supervisors to work collaboratively and effectively with individuals to evaluate both the process and the impact of PCCPs.

Learning Objectives

After completing this module, you will be able to:

- identify the key elements and the importance of a progress note in person-centered approaches;

- learn about different structures of writing a progress note;

- understand the value of utilizing the person-centered plan to guide everyday practice;

- understand the definition and benefits of concurrent documentation;

- identify strategies to solicit active service user involvement in ongoing CQI initiatives;

- identify workforce development needs and recovery-specific competencies.

Learning Assessment

A learning assessment is included at the end of the module. If you are already familiar with this subject, you may want to go to the end of this module and take the assessment to see how much you already know. Then you can focus your learning efforts on what is new for you.

Charting to the Plan

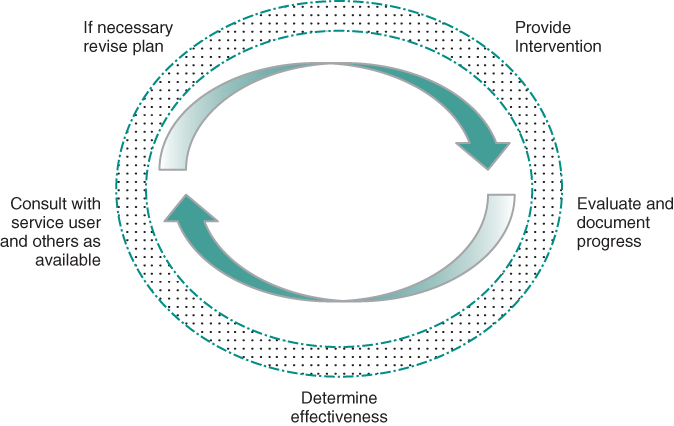

So you and the person you are working with have collaborated with your team to develop a person-centered care plan (PCCP). The document is complete and signed, with all parties agreeing on the respective roles they have to play in promoting the person’s recovery. What now? Often times, this is when the plan is filed in a chart and forgotten until 90 days or 6 months have passed, after which it is unearthed and revisited only to be rewritten and filed all over again. The document itself is “dead,” with no life, value, or function in your everyday work of assisting people in moving toward their goals, hopes, and dreams (Figure 7.1).

Figure 7.1 Cyclical Path for Developing, Implementing, and Revising Care Plan

A person-centered process should ideally result, instead, in a plan that can function as a roadmap, a tool that is referred to often as a guide for anticipating what the next steps moving forward entail. Having the plan function as a live and active reference point can sometimes require a dramatic change in process and practice, as this may not be the way many practitioners are accustomed to working. And if it requires a change for practitioners, then it will also require a change for those receiving services as well. Making this shift requires education for all involved, and a thoughtful process of reviewing and revising practices as we move toward the person-centered ideal of using the plan as a roadmap for everyday life.

As with any trip, though, it is important to check in on our progress: Are we on the right road? Do we need to change direction? Are there other people we might need to invite along to help us navigate the next leg of the journey? Part of this assessment is included in the documentation recorded at each meeting when interventions are being provided and the work and progress being made by the person receiving services is reviewed.

As a mental health practitioner you are no doubt familiar with progress or encounter notes, the documentation of each contact or service provided for a person receiving services. What follows here is a brief note on the purpose of progress notes, which may be more of a review but might also provide a new rationale for the note-taking process. Documentation in the clinical record is an integral part of providing mental health services. Though it may seem obvious why it is important, we briefly review here several of the reasons that charting is an essential, if perhaps underappreciated, component of providing person-centered care.

Progress notes are an integral part of the PCCP process. A strongly and clearly written plan directly informs the tasks to be achieved as well as the progress notes to be written. In this way, the plan is an integral part of services and their documentation. To write a note, it is necessary to refer back to the plan, as the notes themselves should correspond to one or more objectives within the plan.

Benefits of utilizing the plan this way are multiple. First, it is a transparent and accessible way of working; all members of the team (including the person receiving services) are aware of their roles and others’ roles in making progress toward the identified goals. For the practitioner, the requirements of documentation include charting directly to the stated goals and objectives. This is for several reasons, including making sure that the services provided are appropriate and billable (when relevant).

Importance of Progress Notes

- To record what was done, by whom, when, and with what effects.

- To describe significant changes in the person’s status.

- To evaluate progress in relation to the goals and objectives on the care plan.

- To record consultations with other providers or natural supports.

- To facilitate communication and coordination.

- To provide a record of the person’s recovery journey.

- To serve as a supervisory tool; supervisors use progress notes to see what you have been doing.

Progress notes are about evaluating the impact of the services provided within the context of the person’s care plan. In this sense, they represent an important opportunity to reflect on whether or not the plan, as written, is helping the person to achieve his or her objectives and move closer to his or her recovery goals. If notes routinely reflect that a person is not making progress, it can be an indication that a roadblock has been encountered and a mid-course correction is needed. Finally, progress notes also work to ensure there is accountability among all stakeholders who have committed action steps to the plan, including the person in recovery and his or her natural supports. This is critical, as even the very best person-centered plan is only as good as its implementation and follow-through!

Essential Elements of a Progress Note

Specific pieces of information are key to include in any progress note. These vary by organization and funder, but generally must include, at a minimum:

- Name of person and other identifying information (e.g., medical record number)

- Date of service

- Location

- Time involved (including the duration of service as well as the specific time that services were delivered)

- What services were provided

- Signature, including discipline, and supervisor co-signature if required

Notes must accurately reflect the activity, location, and time for each service. The time indicated within the note includes the time spent in travel to deliver the service, plan progress review for the next steps, the actual provision of the service, and the documenting of the service.

As part of a person’s medical, clinical, or health record, progress notes are considered legal documents. It is important that practitioners remain mindful of this status as they document their work and its impact. In addition to meetings with service users, practitioners need to document non-routine calls, missed sessions, and consultations with other professionals. Throughout, though, make sure that the focus is on the work being done and the person being served. Chart the person’s successes as well as any significant concerns you may have, particularly if the person is disconnecting from care and you have concerns regarding his or her welfare. Given that progress notes and the chart as a whole are a legal document, remember that these can be subpoenaed at any time.

Types of Progress Notes

You may have a note writing system that is prescribed by your agency. The following are several examples of structuring the progress note itself into key elements. Each has an acronym that represents the different content areas of the note.

Elements of a DAP Note

- Description: service delivered, impression of person, significant events, and status.

- Analysis/Assessment: progress toward goals/objectives/interventions on the plan, person’s response, and staff strategies.

- Plan: the next contact, staff task, person in recovery task, or natural supporter task.

The DAP (Description, Analysis, and Plan) note starts with a description of the important information observed along with interventions, followed by an assessment of the person and of his or her response to the interventions, and concluding with a plan for the next steps, including the staff’s next step, date of next contact, and any tasks for the person receiving services and his or her natural supporters.

Elements of a SOAP Note

- Subjective: what the service-user states.

- Objective: what you observed.

- Assessment: description of the person’s behavior/movement toward goals—not necessarily CLINICAL assessment.

- Plan: the next contact, staff tasks, and person’s tasks.

A second format for the progress note is that of SOAP. SOAP notes start with the “subjective,” which includes what was said by the person receiving services, followed by “objective,” or what you observed as the practitioner. Next, similar to the DAP note, is the “assessment”: this is a description of the person’s response and any progress following the intervention, including specifically addressing the movement toward objectives and goals. This note also ends with the plan for the future, including the staff’s next step, date of next contact, and any tasks for the person receiving services and his or her natural supporters.

A third kind of progress note structure is the GIRPS (Goal, Intervention, Response, and Significant Observations). This is probably the most useful structure for writing billable progress notes for person-centered care approaches, as it includes the Goal and Objective aspect in the structure of the note. Continuously reflecting on these aspects of the plan serves as an important reminder of the person’s most valued recovery goal, and keeps the team collectively focused on working together to help them move forward toward this destination.

Elements of a GIRPS Progress Note

- Goal: related goal(s) and objective(s) from the plan.

- Intervention: a description of the specific activities performed by the staff.

- Response: person/family response to the above specific intervention; encourage inclusion of person/family self-assessment of response as well as staff assessment.

- Plan for the next steps within the context of interventions and response.

- Significant Observations: description of the person’s presentation that is different from usual presentation including any recent or current circumstances that need to be taken into consideration.

An organization may decide to use any of these structures to document the work and progress being made with a person in recovery. Regardless of what structure is utilized, it is important to include aspects of culture and context within the content of the note, as discussed in the next section.

Maintaining the Person-Centered Dimension of Progress Notes

When writing notes, technical elements are essential to include in addition to following whatever structure or format your agency or organization has decided to use. At the same time, the content of the note should not be overshadowed by the structure and technical detail. Without minimizing these aspects (as they are key to quality plan implementation as well as the billing and payment for services), we need to consider the language and other elements that should be considered in writing the note.

In terms of language, for example, as much of the progress note as possible should be written in everyday language so that the person receiving the services would be able to understand what has been recorded. Especially when concurrent documentation is being used (see below), it will be important for service users to review what is being recorded in their health record and be given an opportunity to provide their input on the content. Even when this is not the case, the language used in progress notes should mirror as much as possible the language used in the PCCP, which, as we suggested in Module 2, should be accessible to the person and his or her natural supporters.

We are not suggesting that diagnostic and clinical terms can never be used, however. What we are suggesting is that when it is necessary to use such terms, they should be accompanied by a description in everyday language of how what they are referring to is seen or experienced in the person’s everyday life. A common example of this would be describing the clinical phenomenon of “auditory hallucinations” as hearing the voices of significant figures in the person’s life, which may be either harsh and critical or supportive and helpful (or a combination of both). Other examples include describing “thought disorder” or “cognitive disruptions” as having difficulty keeping thoughts together or having difficulties with concentration, memory, or following the thread of a conversation. Similarly, “hypomania” can be described as increases in activity rates or levels, “dysthymia” as sadness, and “mood lability” as unexpected changes in the person’s moods over time. When framed in these ways, persons being served can learn to identify their difficulties, and signs of progress, taking on a more active and collaborative role in their own care.

Just as in the strength-based assessment and plan development, it is also important to consider cultural elements when composing progress notes. As every interaction represented the convergence of multiple cultures (e.g., the practitioner’s cultural identity and background, the service user’s cultural identity and background, the culture of the health care system), it is important as a practitioner to reflect these forces within the documentation of the note. This can include recording particular preferences and observations that are related directly to culture and referring to a person’s background and worldview and how these impact your assessment, interventions, and plan. Cultural factors should be considered along with the person’s own understanding of his or her situation and needs, especially to avoid viewing culturally influenced interpretations of these experiences as pathological. Seeing or hearing the voice of a deceased relative, for example, is considered a normal part of the grieving process in many cultures and does not always indicate the presence of hallucinations, which is understood as symptoms of an underlying illness. Important in this process is to be reflective about one’s own biases and to be aware of potential personal pitfalls.

Concurrent Documentation

One approach to writing progress notes that was designed to increase efficiency, but which can also promote person-centered care, is writing it concurrently. This means writing the note while the person is actually meeting with you and having him or her review it (and perhaps even include his or her input). Doing so ensures transparency of the process and efficiency in terms of not having to wait until the person leaves to complete your documentation. Some of the benefits of concurrent documentation include1:

- Staff satisfaction—Staff are often weary of paperwork, especially when it seems to limit the amount of time that can be spent providing direct care. Engaging in concurrent documentation can free up valuable time to provide services and complete other requirements for staff, including supervision and consultation.

- Compliance with submission and billing requirements.

- Supports recovery-focused services through service user participation and benefit. The philosophy of recovery-oriented care also consists of increasing the transparency and including the person receiving services in as many aspects of care as possible. Inclusion in the process of documentation serves as a way of demystifying the process and furthers a sense of partnership.

- Empowers the person and family to be aware of and to influence the course of clinical assessment and interventions by providing a built-in point of shared reflection regarding the progress or lack of progress toward recovery goals. It involves the person in the recording of what happened, and can significantly improve communication by more quickly addressing misunderstandings or clarifying miscommunications.

- Increases person and family “buy-in” to care through real time feedback. The consistent and regular checking in with a person receiving services, or his or her loved ones, regarding their perceptions of progress can provide yet another point of engagement and alliance building in doing this collaborative work.

- Significant positive impact on engagement in services and rates of medication adherence [1]. A recent study with 10 CMHCs across the country examined the impact of person-centered planning training when combined with concurrent documentation. When compared to a control group providing standard care, the PCP and concurrent documentation intervention were associated with significantly greater engagement in services (as measure by decreases in appointment “no shows) and higher rates of medication adherence (as measured by clinician assessment and informed by self-report). Perhaps due to the increased “buy-in” referred to above, these study findings suggest that when individuals have greater control over their treatment through the creation of a person-centered plan that is squarely focused on their personal goals, they are more likely to actively participate in the therapeutic process and to take advantage of the recovery tools being offered to them.

Concurrent documentation should not interfere with the collaborative nature of the work being done with the person receiving services. Using concurrent documentation means being systematic and well-planned about the time spent together in order to allow time to conduct concurrent documentation in collaboration with the person “not to interrupt a session, but as a collaborative effort between provider and client at the end of a session.”2

When to Review the Plan

To keep the plan an active and “living” document, useful in the everyday provision of services and working toward goals, it is important to update the plan regularly and as necessary. Typically, plans are required by regulators to reassess quarterly—every 90 days—and this is the national standard as well. A plan that is built on 90-day increments demonstrates belief in change as it communicates a hopeful expectation of progress and movement within a relatively short time frame.

Reviewing the plan is also key to evaluate the effectiveness of the interventions being provided at each meeting and subsequently to determine whether or not the plan itself needs to be revised. This is especially important if a new intervention is to be determined as needed. It also is the case that in order to bill for interventions, they need to be indicated on the plan. Therefore, as soon as possible, the plan should be revised to include new interventions and this, too, should be done as much as possible in consultation with the person receiving services.

Objectives may need to be revised if you realize that you and/or the person you are working with have been too ambitious and have bitten off more than what you can chew. An example would be a person who is interested in going back to college has set as an objective to “complete one college class with a grade of at least a ‘B’ in the next 90 days.” If in 3 weeks’ time, the person has yet to enroll or even pick up the phone to make a call to the registrar’s office, the goal will be too much of a step to start out with. This does not mean that the goal is unobtainable, but instead that you are presented with a chance to reevaluate the relative “size” of the objective with regard to where the person is now in his or her recovery. PCCPs should be designed as much as possible to build on successes; to do so, it is important to balance the high expectations of a recovery-oriented system (and of service users and families) with a realistic assessment of where the person is in his or her recovery at any given time, along with the resources he or she has at his or her disposal. It is possible, for example, that the person did not call the registrar because he or she cannot afford to enroll at that time. So when agreed-upon objectives appear to be out of reach, it may require both the practitioner and the person to scale back to more incremental steps that are achievable within the designated time frame. As described in Module 6, breaking long-term goals down into achievable, shorter-term objectives requires clinical skill and resourcefulness; the same is true of breaking ambitious objectives down into the intervening steps that need to be taken to get there.

Another possibility for the plan update is to consider adding or removing interventions as necessary and as the person’s condition evolves. To continue the above example regarding someone interested in returning to college, if the original set of interventions had not included a supported education component, it could be added to the plan so that a supported education counselor could support the person in making the transition into taking first a college class after a lengthy absence from academics.

The input of the person being served is essential in person-centered plan updates, just as it is in the initial development of the plan. When rewriting and reevaluating the plan on an interim basis (revisions between the full plan review), it is useful, as much as possible, to include natural supports and family members as desired by the service user. This may not be possible in all circumstances, but is something to work toward whenever possible. Finally, remember that reviews of the plan should not be triggered only by crisis events. In a recovery-oriented planning process, it is equally important to be future-focused and goal-oriented. Therefore, the team should reconvene around events of success/accomplishment as well as crises to revisit care plans and discuss next steps.

What we have described thus far is how an individual’s plan is to be reviewed and revised on an ongoing basis as his or her recovery unfolds over time. A parallel process can also take place at the agency or organizational level, as the process of care planning can itself become the object of review and revision as one focus of continuous quality improvement (CQI). It is to this topic that we turn next.

The Role of Continuous Quality Improvement

Quality improvement is achieved by setting goals and objectives, developing performance indicators to measure the objectives, and collecting diverse data on system performance.

—California Mental Health Planning Council, Partnerships for Quality [3]

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree