CHAPTER 65 Aggression and Violence

OVERVIEW

Aggression and violence are complex behaviors that occur both inside and outside of the medical setting. Because of the complex nature of aggressive and violent behavior, this chapter focuses on the differential diagnosis of aggressive acts as it pertains to the medical and psychiatric setting. An exhaustive review of aggression and violence within society and its larger economic and sociocultural impact is beyond the scope of this chapter.1,2 Although workplace violence has a significant impact on the medical and hospital environment, it is not discussed here.3,4 In an era of growing experience with the effects of terrorism and the residual psychological and behavioral effects on tortured patients, psychiatrists must be able to recognize the complex biopsychosocial context of each patient who displays aggressive behavior given the patient’s unique personal history.5 Traumatic brain injury, which leads to impulsive and aggressive behavior, may be the first evidence of a patient’s trauma or torture history.6

This chapter will discuss a systematic approach to the management of patients with aggressive and violent behaviors. Care of the violent or impulsive patient poses a serious challenge to the psychiatrist, who needs to both rapidly and accurately assess the cause of aggression while initiating treatment. In the medical setting aggressive behavior can be associated with delirium, dementia, and other organic medical conditions; hence, ruling out medical causes must precede the consideration that the behavior is the consequence of antisocial personality disorder or other types of character pathology.7 The psychiatrist must have a frame of reference to adequately assess for the risk of violence, as well as the skills to manage it.8

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND RISK FACTORS

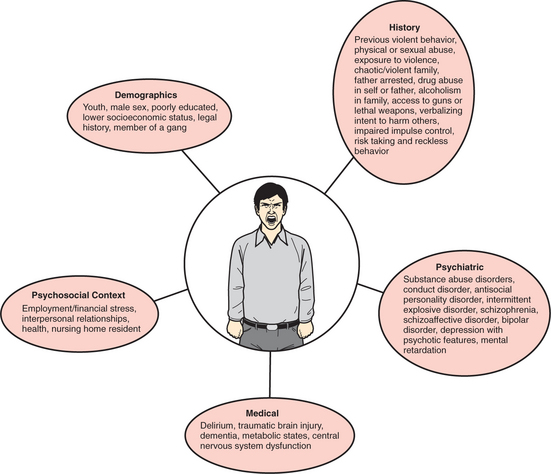

There is debate as to whether individuals with mental illness are at greater risk for violence than are those in the general population. Current data suggest that people who suffer from mental illness commit violent acts more than twice as often as individuals without a psychiatric diagnosis.9–13 The Bureau of Justice Statistics has reported that 283,800 individuals with mental illnesses were confined in United States jails and prisons in 1998; they often had co-occurring substance abuse disorders.14 In Sweden it was found that 5.2% of the population’s attributable risk for violent crime was due to individuals with severe mental illness, and similar rates have been found within the United States.15 The elevated rates of violent behavior are of special concern to health care providers: patients with schizophrenia who are acutely agitated are thought to account for over 20% of psychiatric emergency department visits, and more than 70% of patients (living in nursing home facilities) with dementia exhibit signs of agitation.16 Of note, however, is the fact that the large majority of people with mental illness do not commit violent crimes: the MacArthur Study on violent behavior in the mentally ill population found that violence is more prevalent than it is in the general population only if substances of abuse are involved or if the patients are not appropriately medicated.17 Studies have also shown that up to 25% of the mentally ill have reported that violent acts have been committed against them; this is more than 11 times greater than it is in the general public, and it is itself a risk factor for the propagation of violent behavior.18 Therefore, while having a psychiatric diagnosis puts one at increased risk, other factors (including demographics, personal history, medical diagnosis, and psychosocial stressors) often act in an additive manner to define one’s likelihood of committing a violent act (Figure 65-1).

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Violent acts and aggression have biological, environmental, and psychological determinants.10,19 While there has never been an identifiable “aggression center” in the brains of humans, many animal studies have implicated several brain regions that may be involved in the hierarchical control of this complicated set of behaviors. Some of these areas are excitatory in nature; others are inhibitory.19–23 The hypothalamus regulates neuroendocrine responses through output to the pituitary gland and the autonomic nervous system. Within the hypothalamus, the anterior, lateral, ventromedial, and dorsomedial nuclei often are described as areas crucial to animal aggression; they are considered to be involved in the control of aggression in humans. The limbic system (which includes the amygdala, hippocampus, septum, cingulate, and fornix) has regulatory control of aggressive behaviors in humans and animals. The prefrontal cortex modulates input from both the limbic system and the hypothalamus; it may have a role in the social context and judgmental aspects of aggression.24

Neuroimaging studies have allowed clinicians to examine brain function in violent people, and have repeatedly found abnormalities in their prefrontal areas. Using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques, violent individuals have been shown to have reductions in the volume of their prefrontal gray matter. Using single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) techniques, it has been shown that adolescent and adult psychiatric patients who had recently participated in an aggressive act had significantly depressed prefrontal activity when compared with control patients. Multiple positron emission tomography (PET) analyses have illustrated that violent patients have decreased prefrontal/frontal blood flow and metabolism.25 These findings are supported by clinical evidence that acquired lesions within, as well as injury to, the prefrontal cortex and frontal lobe put one at increased risk for impulsive behavior and contribute to less executive control of emotional reactivity (see Chapter 81). Multiple SPECT and PET analyses have also found abnormalities within the temporal lobe and the subcortical structures of the medial temporal lobe in violent patients.26

Low central serotonin (5-HT) function has been correlated with impulsive aggression. Violent patients have been found to have a low turnover of 5-HT, as measured by its major metabolite 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Acetylcholine in the limbic system stimulates aggression in animals; cholinergic pesticides have been cited as provoking violence in humans. Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is thought to have inhibitory effects on aggression in both humans and animals. Norepinephrine may enhance some types of aggression in animals and could play a role in impulsivity and episodic violence in humans. Dopamine increases aggressive behavior in animal models, but its effect in humans is less clear because of its psychotomimetic effects.27–29 Hormonal influences of androgens often are cited as a major factor in aggressive behavior because they may play an organizational role in the development of these behaviors. Some attribute a lower threshold for violence in women to lower levels of estrogen and progesterone during the menstrual cycle. More recently, lower cholesterol levels in patients with personality disorders have been associated with aggressive and impulsive behavior30,31 (Table 65-1).

Table 65-1 Neurochemical Changes Associated with Increased Aggression

| Neurochemical | Change in Plasma |

|---|---|

| Serotonin | Decreased |

| Acetylcholine | Increased |

| Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) | Decreased |

| Norepinephrine | Increased |

| Dopamine | Increased |

| Testosterone | Increased |

| Cholesterol | Decreased |

In considering the genetics of aggressive and impulsive behavior, there have been no specific chromosomal abnormalities yet associated with an increased risk for aggression. Using twin studies, a meta-analysis that examined the etiology of aggressive behavior showed that at least 50% of the pathology could be attributable to genetics.32 The relationship between the syndrome involving XYY and impulsivity is questionable, and the relationship remains inconclusive. Knock-out mice that lack the MAOA gene (which encodes for the enzyme responsible for the catabolism of serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine, and subsequently leads to elevated serum levels of the three neurochemicals) were shown to exhibit increased aggression in genetic studies. A family in the Netherlands had an X-linked mutation in this gene, and the affected members showed increased levels of aggressive behavior. Human clinical correlates also exist for the mouse knockout studies that examined COMT (an enzyme also responsible for the catabolism of catecholamines) gene mutations leading to increased aggression.33 A recent study that examined the serotonin transporter gene (which regulates the duration of serotonin signaling) showed that a polymorphism in the promoter yielded low serotonin levels and increased aggressive behavior in children.34 Polymorphisms of tryptophan hydroxylase may also be correlated with impulsive aggression.

CLINICAL FEATURES AND DIAGNOSIS

The etiologies of aggressive and violent behavior are vast; however, if they can be identified, it is critical to do so, because the management, in both the acute and long-term setting, relies on this information. It is critical for the evaluator to assess whether the pathology is a result of major mental illness on Axis I, a result of a personality disorder (as described on Axis II), or a result of a medical condition (listed on Axis III) because the level of acuity, the degree of violent behavior, and the treatment approach of each type of problem will vary. When beginning the assessment of a violent patient, it is useful to generate a working differential (Table 65-2).

Table 65-2 Differential Diagnosis of Psychosis and Agitation

| General Category | Cause/Diagnosis |

|---|---|

| Organic mental disorders | Aphasias |

| Catatonia | |

| Delirium | |

| Dementia | |

| Frontal lobe syndrome | |

| Organic hallucinosis | |

| Organic delusional disorder | |

| Organic mood disorder (secondary mania) | |

| Seizure disorders | |

| Drugs | Substance abuse (e.g., cocaine and opiates) |

| Steroids | |

| Isoniazid | |

| Procarbazine hydrochloride | |

| Antibiotics | |

| Anticholinergics | |

| Drug withdrawal | Alcohol and sedative-hypnotics (barbiturates and benzodiazepines) |

| Clonidine | |

| Opiates | |

| Psychotic disorders | Schizophrenia |

| Delusional disorder | |

| Psychotic disorders not otherwise specified (NOS) | |

| Brief reactive psychosis | |

| Schizoaffective disorder | |

| Shared paranoid disorder (folie à deux) | |

| Mood disorders | Manic-depressive disorder |

| Major depression with psychotic/agitated features | |

| Catatonia | |

| Anxiety/fear | Anxiety disorders |

| Acute reaction to stress | |

| Discomfort | Pain |

| Hypoxia | |

| Akathisia | |

| Personality disorder | Antisocial |

| Borderline | |

| Paranoid | |

| Schizotypal | |

| Disorders of infancy, childhood, or adolescence | Autism |

| Mental retardation | |

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder | |

| Conduct disorder |

Medical Causes (Axis III)

One must first assume that there is a medical condition or a substance abuse/dependence problem that is causing aggressive behavior before considering primary psychiatric disorders. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR)35 classifies medical causes of mental disorders (Table 65-3).

Table 65-3 Medical Causes of Mental Disorders

HIV, Human immunodeficiency virus; PCP, phencyclidine; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.