CHAPTER 70 Geriatric Psychiatry

OVERVIEW

The population older than 65 years has increased dramatically over the past several years; this trend reflects improved health, nutrition, and access to medical care. This remarkable lengthening of the average life span in the United States, from 47 years in 1900 to more than 75 years at present, will continue to increase along with improvements in medicine and the health consciousness of the baby boomers.1 Equally noteworthy has been the increase in the number of those over age 85. Older adults continue to learn and to contribute to society, despite the physiological changes associated with aging and the ever-threatening health and cognitive problems they face. Ongoing intellectual, social, and physical activity is important for the maintenance of mental health at all stages of life. Stressful life events (e.g., declining health; loss of independence; and the loss of a spouse or partner, family member, or friend) typically become more common with advancing age. However, major depression, anxiety disorders, memory loss, and unrelenting bereavement are not a part of normal aging; they should be treated when diagnosed. A host of effective interventions exist for most psychiatric disorders experienced by older adults and for many of the mental health problems associated with aging.

The prevalence of medical and psychiatric illness increases with advancing age in part due to stressful life events, the burden of co-morbid illness, and the various combinations of a bevy of medications used.2

The reduction in hepatic, renal, and gastric function impairs the elder’s ability to absorb and metabolize drugs; aging also influences the enzymes that degrade these medications (Table 70-1).1

Table 70-1 Metabolic Changes Associated with Aging

| Function | Impact | Domain |

|---|---|---|

| Hepatic function | Decreased | Blood flow |

| • Affects first-pass effect | ||

| Decreased | Enzyme activity | |

| • Demethylation | ||

| • Hydroxylation | ||

| Absorption | Decreased | Blood flow |

| Acidity | ||

| Motility | ||

| Gastrointestinal surface area | ||

| Renal excretion | Decreased | Blood flow |

| • Can lead to lithium toxicity | ||

| Glomerular filtration rate | ||

| • Hydroxymetabolites affected | ||

| Tubular excretion | ||

| • Benzodiazepine clearance slowed | ||

| Distribution | Increased | Volume of distribution |

| • Especially for lipophilic drugs | ||

| Increased | Fat stores | |

| Decreased | Water content | |

| Decreased | Muscle mass | |

| Decreased | Cardiac output and perfusion to organs | |

| Protein-binding | Decreased | Albumin levels (except alpha1-glycoprotein) |

Disability due to mental illness in elderly individuals will increasingly become a major public health problem in the very near future. The elderly are more susceptible to disease and more vulnerable to the side effects of prescribed drugs and other substances (be they illicit or over-the-counter substances).3 Approximately 40% to 60% of hospitalized medical and surgical patients are over 65; they are at greater risk for functional decline while hospitalized than are younger individuals.4 Adequately treating older adults who have psychiatric disorders provides benefits for their overall health by improving their interest and ability to care for themselves and to follow their primary care provider’s directions and advice with regard to health promotion and medication compliance. Older individuals can also benefit from advances in psychotherapy, medications, and other treatment interventions for mental disorders, when these interventions are modified for age and health status.

An understanding of geriatric mental health relies in part on an appreciation of neurochemistry. Neurochemistry of the aging human brain is closely related to an irreversible loss of function and a decline in global abilities. Fortunately, our brain has remarkable plasticity; it allows for the well-designed compensation for neuronal loss and functional decline that is linked with an age-related loss in neurons, dendrites, enzymes, and neurotransmitters.5 Enzymes and neurotransmitters in the brain change as we age; monoamine oxidase increases and acetylcholine and dopamine decrease.6

MENTAL HEALTH DISORDERS COMMON IN LATE LIFE

Late-Life Depression

Depression in late life lowers life expectancy. Depression and cognitive impairment affect approximately 25% of the elderly.1 New research confirms that the risk for stroke increases especially in the “old-old” (i.e., those over 85 years of age).7 Diagnosis is not more common according to Epidemiological Catchment Area (ECA) data; however, making the diagnosis is more difficult. A higher rate of depression exists in older women as compared to older men; among those with a history of depression there is a 50% chance of a second episode (either a recurrence or a relapse).8 Use of medications for medical problems often generates adverse effects and complicates the diagnosis of depression; moreover, medical illness may mimic depression and depression may mimic medical illness. Depression (as occurs with stroke, fractured hip, arthritis, and cardiac illness) is common in disabled elderly. Depression is also associated with both acute and chronic medical illness and late-onset depression is closely associated with physical illness.9 Of note, undiagnosed medical illness can manifest as depression. Grief and loss may also contribute to depression. As many as 60% of depressed patients have co-morbid anxiety and 40% of anxious patients have co-morbid depression.10

Neurological disorders also complicate the diagnosis of depression. The risk for depression in the post-stroke period is high, with 25% to 50% developing depression within 2 years of the event.7 Alzheimer’s disease (AD) carries an increased risk of depression; approximately 20% to 30% (either before or at the time of diagnosis) are diagnosed with depression; delusions are also prominent in depression associated with dementia.11 Recent research confirms the association of depression with the increased risk of developing late-onset AD.12 Fifty percent of patients with Parkinson’s disease develop depression or have a history of depression with anxiety, dysthymia, or frontal lobe dysfunction.13 Degeneration of the subcortical nuclei (especially the raphe nuclei) is related to the development of depression in Parkinson’s disease.

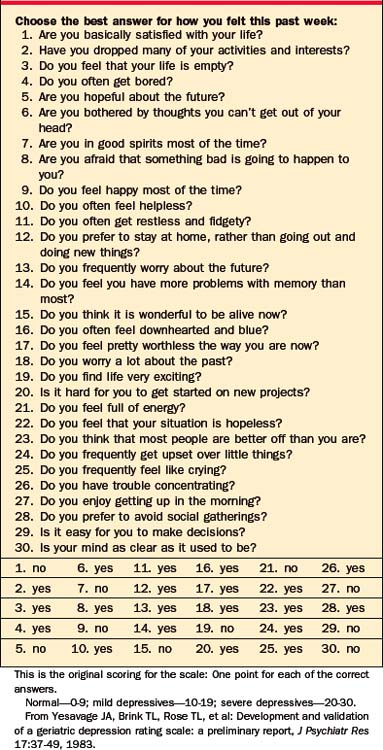

Assessment of depression can be challenging. The Geriatric Depressions Scale (Table 70-2)14 is a helpful tool in this regard, and often the information provided by the caregiver is crucial as elders may not be forthcoming with their symptoms.15 The criteria for diagnosing depression at this time as the same as they are in the general population.

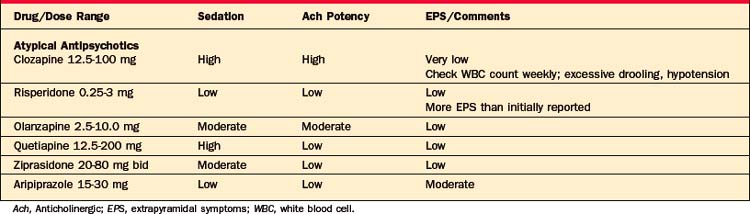

Treatment of late-life depression is challenging in part because there is a decline in one’s biological ability to metabolize drugs and to bind proteins, because of reduced receptor sensitivity, as well as an increased sensitivity to drug side effects. In an effort to reduce adverse consequences of medications, drugs with the fewest side effects should be started (and be used in small doses); in addition, monotherapy should be attempted16,17 (Tables 70-3 and 70-4). In more refractory cases or with psychotic symptoms, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) should be considered early in treatment and as an adjunct for one or more drugs.18 Individual psychotherapy or group therapy complements somatic treatments and often leads to a swift recovery. Interpersonal therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) are both suited to this population as they are more focused and interactive treatments.19

Table 70-3 Medications for Depression in the Elderly

| Drugs | Dose Range | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Tricyclic Antidepressants | ||

| Nortriptyline | 10-150 mg/day | Reliable blood levels, minimal orthostasis |

| Desipramine | 10-250 mg/day | Mildly anticholinergic |

| Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors | ||

| Tranylcypromine | 10-30 mg/day | Orthostasis (possibly delayed), pedal edema, weakly anticholinergic, requires dietary restrictions |

| Stimulants | ||

| Dextroamphetamine | 2.5-40 mg/day | Agitation, mild tachycardia |

| Methylphenidate | 2.5-60 mg/day | |

| Modafanil | 50-200 mg/day | |

| Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors | ||

| Fluoxetine | 5-60 mg/day | Akathisia, headache, agitation, gastrointestinal complaints, diarrhea/constipation |

| Sertraline | 25-200 mg/day | |

| Paroxetine | 5-40 mg/day | |

| Fluvoxamine | 25-300 mg/day | |

| Citalopram | 10-40 mg/day | |

| Escitalopram | 2.5-20 mg/day | |

| Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs) | ||

| Venlafaxine | 25-300 mg/day | Increase in systolic blood pressure, confusion, light-headedness |

| Nefazodone | 50-600 mg/day | Pedal edema, rash |

| Duloxetine | 20-60 mg/day | Diarrhea |

| Alpha-2 Antagonist/Selective Serotonin | ||

| Mirtazapine | 15-45 mg/day | Sedation, weight gain |

| Atypical Antidepressants | ||

| Trazodone | 25-250 mg/day | Sedation, orthostasis, incontinence, hallucinations, priapism |

| Nefazodone | 50-600 mg/day | Pedal edema, rash |

| Bupropion | 75-450 mg/day | Seizures, less mania/cycling, headache, nausea |

Late-Life Depression and Suicide

Depression with psychotic features is linked with a higher risk of suicide. The rate of suicide in those greater than 65 is double that of the rate for the United States population in general, and those with the highest suicide rates of any age-group are those ages 65 years and older.20

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree