INTRODUCTION

Global health and behavioral medicine intersect in two important ways. First, mental, neurological, and substance use (MNS) disorders affect every community in the world. We relate to MNS disorders at a local level, where they are embedded in our customs, culture, and context. MNS disorders also exert global influence, through their massive burden of disease, the human and economic costs of treated and untreated illness, and their secondary (often less visible) effects on the outcomes of other health conditions.

Second, the integration of behavioral, social, and biomedical sciences can improve health care globally. Adapting interdisciplinary lessons to tackle local problems may result in more effective, efficient, and responsive health care delivery. Similarly, understanding the interdependence of social determinants, health, and development may inform enlightened approaches to promoting health and empowering communities.

An interdisciplinary approach also has important implications for health worker training. Health workers in all settings should be trained to treat and prevent behavioral, social, and biological problems. They should be taught communication, leadership, and team membership skills. Burnout among health workers begins during training and leads to a range of dysfunctional behaviors. While learning to care for others, health workers should also be taught to care for themselves.

The intersection of global health and behavioral medicine is a complex and rapidly evolving area. With the goal of offering students a concise entry point into the relevant issues, we have organized this chapter into four sections:

The global treatment gap.

The need for new models of care.

The importance of context.

Health worker training and support.

THE GLOBAL TREATMENT GAP

To appreciate the global treatment gap, we must first understand the level of need. One in four people will suffer from a mental illness in their lifetime. Major depression is the third largest contributor to the overall global disease burden and is expected to be the number one contributor by 2030. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that nearly 850,000 people commit suicide annually. Eighty percent of these suicides are in low- and middle-income countries. As a group, MNS disorders (including conditions such as depression, substance abuse, schizophrenia, dementia, and epilepsy) account for 14% of the overall global disease burden. According to a recent report by the World Economic Forum, the direct and indirect costs of mental illnesses totaled 2.6 trillion dollars in 2010 alone. By 2030, the cumulative costs are expected to exceed 15 trillion dollars. Underlying these staggering financial costs is a flood of measured and unmeasured human suffering.

Despite the enormous need, MNS disorders have received scant attention globally. Why is this the case? The following section presents a brief gap analysis, charting a cascade of inadequate global response from policy, to funding, to treatment.

At each governance level (international, national, state/province, and local), policies influence funding priorities, timelines, and targets. It is not only health policies but also economic, trade, agricultural, educational, and environmental policies that matter. This is because health in general, and mental health in particular, is closely linked to the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age, which these policies shape. For the purposes of this gap analysis, we will focus on the prioritization of mental health in international and national health policies.

At the international level, significant strides have been made in recent years with the creation of the Mental Health Gap Action Programme (a series of evidence-based care protocols for MNS disorders), the Mental Health Atlas Project (more accurately mapping the global burden of disease for MNS disorders), and the Movement for Global Mental Health (a global advocacy group). Setbacks have also been common, with mental health too often marginalized or ignored in the international policy arena.

BOX 8-1. THE WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION (WHO) ON MENTAL HEALTH

The adoption of a mental health programme must be regarded as a truly historic step taken by the Assembly to bring this new field of medicine into the area of inter-governmental action. The programme … will do much for the implementation of one of the W.H.O.’s fundamental principles – namely, that without mental health there can be no true physical health.

Dr. Brock Chisholm, MD, psychiatrist and first Director General of the WHOSince its inception in 1948, the WHO has engaged at the international health policy level in both mental and physical health. Dr. Brock Chisholm, a psychiatrist and the first Director-General of the WHO, helped articulate the WHO’s holistic definition of health as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”* Over half a century later, the 2005 WHO Ministerial Conference in Denmark continued to advocate for an integrated approach, aptly coining the phrase, “No Health Without Mental Health.†

*Outline for a Study Group on World Health and the Survival of the Human Race. Material drawn from articles and speeches by Brock Chisholm. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1954. Available from: . Accessed December 6, 2012.”

†WHO Mental health: facing the challenges, building solutions. Report from the WHO European Ministerial Conference. Copenhagen, Denmark: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2005.

CASE ILLUSTRATION 1

CASE ILLUSTRATION 1

In the months leading up to the 2011 United Nations General Assembly Special Session (UNGASS) on Noncommunicable Diseases (NCDs), MNS disorders became an issue of considerable debate. Notably, the 2000 WHO Global Strategy for the Prevention and Control of NCDs made no mention of MNS disorders. In 2008, MNS disorders only made it into a footnote in the WHO Action Plan on NCDs. In May of 2010, the UN passed a resolution calling for the UNGASS on NCDs, and the subsequent modalities resolution in December 2010 called for six regional consultations on NCDs.

Although MNS disorders had not featured prominently in discussions up until that point, the WHO Regional Office of Africa consultation in Brazzaville in April of 2011 revealed that MNS disorders, hemoglobinopathies, and injuries were major priorities for the region. Weeks later, African nations and India pushed for the inclusion of MNS disorders and garnered their inclusion in the preamble of the Moscow Declaration, which was approved during the Global Ministerial Conference on Healthy Lifestyles and NCDs.

NEW DELHI: India achieved a major success on the global platform by pushing for inclusion of mental health in the list of non-communicable diseases. India fought alone to get mental disorders included in the non-communicable diseases (NCDs) list at the just-concluded first Ministerial Conference on Healthy Lifestyles and Non-communicable Disease Control in Moscow.

–Excerpt from The Hindu May 5, 2011Unfortunately, MNS disorders were excluded from the list of priority conditions in the 2011 UNGASS on NCDs final summary report and recommendations. Time will tell whether the momentum created by the Global South’s advocacy push for MNS disorders in 2011 will yield tangible results. Following the UNGASS on NCDs, advocacy groups resolved at the 2011 World Mental Health Day to push for a stand-alone UNGASS on MNS disorders.

At the national level, many countries lack mental health policies (which services should be covered, for whom, and at what cost), plans (how these services should be implemented and evaluated), and legislation (to protect the rights of people who are mentally ill). Global disparities exist. Less than 40% of African countries have a mental health policy, compared with more than 70% of European countries. More than 70% of African countries do not have a national mental health plan, compared to more than 80% of European countries who have one. Globally less than 40% of countries have specific mental health legislation. The absence of mental health legislation (or their enforcement) encourages human rights abuses, which have been widely reported and described as a “failure of humanity.”

The policy gaps described above lead to critical funding gaps. Compared to the burden of disease and economic loss they cause, the amount of health care spending targeted to MNS disorders is remarkably low. Again, global disparities exist. While high-income countries spend, on average, 5% of their health budgets on mental health, low-income countries spend around 0.5%. As a result, high-income countries spend 2.6 million dollars on psychiatric medications per 100,000 people each year, while low-income countries spend only 1700 dollars per 100,000 people each year. This funding stream is simply insufficient to build or sustain the necessary people, tools, infrastructure, or services needed to provide effective care for the one out of every four people worldwide who will suffer from MNS disorders in their lifetime.

Increased funding for mental health is needed at national and international levels. Whereas a multilateral, international funding mechanism exists for the prevention and treatment of HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria, no such mechanism exists for noncommunicable diseases, including MNS disorders. The Grand Challenges in Global Mental Health, a joint-initiative between the US National Institute of Mental Health, Global Alliance for Chronic Disease, and other institutions seeking to fund mental health research, represents a step in the right direction.

Policy and funding gaps bear significant responsibility for the massive global treatment gap. Approximately 85% of people with MNS disorders worldwide do not receive appropriate care. Major deficits and global disparities exist in the workforce, essential medicines, and services necessary to provide effective mental health care.

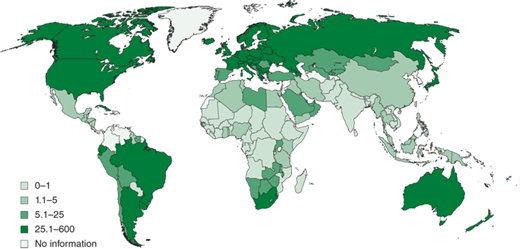

There are insufficient numbers of mental health workers at all levels. These disparities are particularly pronounced in poorer countries. For example, Africa has 0.05 psychiatrists, 0.04 psychologists, and 0.61 mental health nurses per 100,000 people. Staffing levels in the United States and Europe are two to three orders of magnitude higher. New models of mental health care may be able to make better use of (and perhaps expand) the limited mental health workforce, as we discuss later. Nevertheless, the severe shortage of providers, resulting from the withering policy and funding environment, represents a major barrier to delivering safe, effective, community-centered mental health care to all who need it. Figure 8-1 shows the uneven distribution of mental health professionals globally per 100,000 population.

Similar absolute and relative disparities exist in essential medicines for MNS disorders. For example, the antipsychotic section of the WHO Essential Medicines List (EML) has not been modified since 1977. The antipsychotics currently included in the EML (chlorpromazine, fluphenazine, and haloperidol) are significantly more toxic than newer, equally efficacious agents such as risperidone. Worse still, even the outdated medicines included in the EML are often unavailable in low- and middle-income countries. A survey conducted by the WHO in 40 developing nations found that the mean availability of antidepressant medicines was 45.1% in private sector pharmacies and 27.8% in public sector pharmacies. Similar results were found for antiepileptic medicines. Though a full discussion is beyond the scope of this chapter, it bears mentioning that international policies (and the complex factors that determine them) directly shape instruments such as the EML, which profoundly influence the scope of available care in poorer countries. Millions of people live with unnecessary disability, resulting in massive economic loss and, in some cases, conflict and humanitarian crises.

In summary, one in four people suffer from MNS disorders in their lifetime; 85% of these are unable to access appropriate care; and trillions of dollars are lost as a result each year. The causes are complex but knowable. Gaps at the policy level result in insufficient funding which translates into the extreme global shortage of mental health care.

THE NEED FOR NEW MODELS OF CARE

In most of the world, mental health care consists of episodic treatments delivered by psychiatrists in specialized, often locked, facilities. This prevailing model is problematic for four reasons. First, it is too expensive. Teams of mid-level providers and community health workers can be deployed in less time and for a fraction of the cost of training and supporting a single psychiatrist. Second, it fails to achieve sufficient coverage. Even if we assume areas near specialized facilities have access to optimal mental health care (a debatable point), such concentration of resources leaves many areas too far away to maintain longitudinal care. This exacerbates the third problem, which is the overemphasis on treatment at the expense of prevention. The root causes of mental ill health are social as well as biological. If we focus only on the terrible cases that present to the psychiatric hospital, we will miss the forest for the trees. Finally, such treatment models promote stigma and fear surrounding the treatment of mental disorders. This is a particularly sensitive issue in countries where there has been a history of colonialism or violations of human rights by government authorities.

CASE ILLUSTRATION 2

CASE ILLUSTRATION 2

Decades of civil war and authoritarian rule had ruined Liberia’s economy and destroyed its health system. Liberia’s people had suffered enormously. In some areas of the country, an estimated 90% of women had been raped, half of the population had fled the country or been internally displaced, and less than 20% of the population had a paying job. In 2008, a nationwide survey documented a massive burden of mental disorders. Forty percent of Liberian adults had major depression, 44% suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder, and 10% were actively suicidal. In contrast to the overwhelming need, Liberia had only a single psychiatrist, one psychiatric nurse, and one psychiatric facility located in its capital city.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree