INTRODUCTION

This chapter looks beyond the individual patient and clinician to the behaviors of human populations and their impact on the environment, which itself exerts a profound influence on human health and illness. We will discuss opportunities and strategies for modifying those behaviors—on the individual and societal scale—that affect human health and well-being.

The attention of health professionals to environmental factors is warranted by developments in our scientific understanding of three interrelated domains: (1) the impact of environmental degradation and enhancement on human health; (2) the impact of human behavior on the environment; and (3) the effectiveness of initiatives to modify human behavior on a population scale. This chapter will review each of these domains and conclude with suggestions for clinicians to draw upon this information in the care of patients and to become engaged in the process of societal behavior change for the well-being of the planet.

EFFECTS OF ENVIRONMENTAL DEGRADATION ON HUMAN HEALTH

As Hippocrates observed millennia ago, the quality of the biosphere that supports us has a marked impact on our health. Disease burdens due to environmental degradation include altered fertility rates, challenges to the health of newborns, disorders of human development, malnutrition, vector patterns of infectious diseases, skin cancers due to ultraviolet radiation exposure, respiratory disorders, and obesity. Understanding connections between environmental change and these kinds of health problems has increased as agencies such as the World Health Organization (WHO), US National Institutes of Health (NIH), US Centers for Disease Control (CDC), Institute of Medicine (IOM), and others have compiled research on the environment–health connection. A few of these connections are summarized here.

The WHO estimates there are 3 million deaths worldwide each year from air pollutants—3 times the number of traffic fatalities. Over an 18-year period increased death rates from dementias such as Alzheimer and Parkinson have been linked to a rise in the concentration of pesticides, industrial effluents, car exhaust, and other pollutants in the environment. Sulfur dioxide, produced by combustion of fossil fuels, has been shown to induce acute bronchoconstriction in asthmatics. Particulate air pollution has been implicated in respiratory ailments and in derangement of heart rate variability, a risk factor for cardiac events. Carbon monoxide (CO), primarily emitted from internal combustion engines in motor vehicles, has serious health effects in high concentrations leading to carbon monoxide poisoning. More frequently, however, lower-level exposures to CO may increase platelet activity and coagulation, leading to increased risks of thromboembolism. A global meta-analysis found an association between air pollution and heart failure hospitalization or death, particularly with increases in carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, and nitrogen dioxide. In Northern China, where the government’s Huai River policy has provided free winter heating with coal, total suspended particulates (TSPs) air pollution has been associated with a lower life expectancy of 5.5 years, compared with populations in the south. A meta-analysis of 17 population cohorts in Europe found a significant association between particulate matter concentrations and lung cancer.

The quality of water can be associated with human disease in several ways. Bacterial pathogens, including salmonella, Shigella, Escherichia coli, and Vibrio cholerae—all of which cause diarrheal disease, can be spread by water, particularly in developing countries with inadequate water treatment. Water quality is also compromised by various toxic chemicals that accumulate in ground and surface water from runoff and industrial discharge. Examples are nitrates, pesticides, the gasoline additive methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE), radon, arsenic, lead, and the by-products of disinfectants. These toxins have been associated with a variety of health problems, including various forms of cancer, decreased intelligence quotient (IQ) and behavioral problems in infants and children, adult hypertension, and neurotoxicity.

Water availability per capita is shrinking worldwide. The total amount of freshwater available for human use worldwide is about 0.007 of all the water on earth. Currently, humans use about half of this amount. In many underdeveloped parts of the world, millions of humans live in “hydrological poverty,” in which water for direct human consumption through drinking and indirect consumption through grain production is becoming increasingly scarce. In these areas, water for drinking and irrigation is over-pumped beyond the recharge rate of underground aquifers. Resource wars, in which arable land is contested in civil wars, such as that occurring in the Darfur region of Sudan, are increasing in frequency due to diminished water availability for irrigation.

Of the 7.2 billion comprising the earth’s human population, over 4 billion are prone to malnourishment of some form. Hunger afflicts 1.2 billion; another 2 billion suffer from micronutrient deficiency. Most of these people live in the preindustrial or developing world. At the other end of the malnourishment spectrum, 1.2 billion people, primarily in the developed world, suffer from over-consumption of food with its associated problems of obesity, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes.

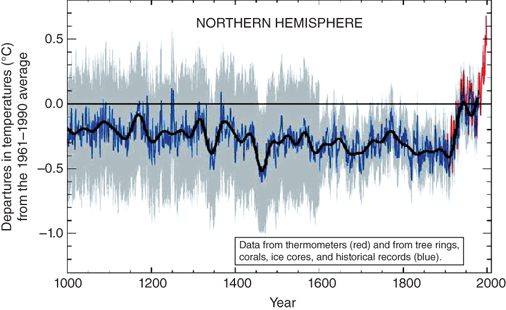

There is a preponderance of evidence from various domains of scientific measurement that the earth’s climate is warming at an alarming rate that exceeds the normal background fluctuation of temperature. Global temperatures have been rising steadily for nearly 40 years; 9 out of the 10 warmest years on record have occurred since 2001; and the global combined land and ocean surface temperature for 2010 was tied with 2005 as the warmest years on record, at 0.62°C above the twentieth century average. Figure 9-1 shows the increase in the Northern Hemisphere temperature over the last thousand years.

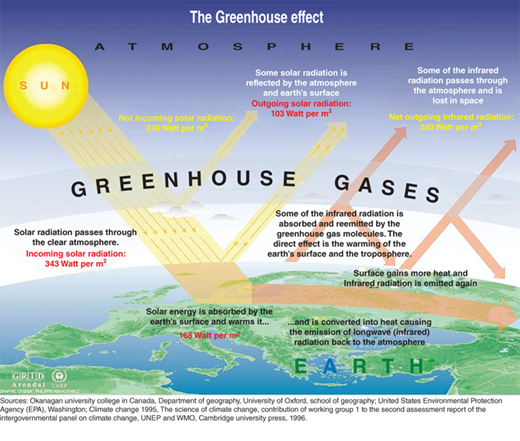

The major driver of this global warming is the accumulation of “greenhouse” gases—primarily carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide—which reached their highest concentrations over the last millennium during the 1990s. These greenhouse gases allow radiant energy from the sun to be absorbed by water vapor, clouds, and aerosols, and then trap the reflected infrared radiation, absorbing and reemitting it to further warm the lower atmosphere and the earth’s surface (see Figure 9-2).

Figure 9-2.

The greenhouse effect on earth’s atmosphere. (Greenhouse gases, which include water vapor (H2O), ozone (O3), carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and nitrous oxide (N2O), are able to absorb and reemit infrared radiation, while not blocking visible light. The greenhouse effect occurs when solar radiation is absorbed by the earth’s surface, converted into heat, and subsequently emitted into the atmosphere as infrared radiation. Some of this infrared radiation escapes into outer space; however, some is absorbed and reemitted back toward the earth’s surface by greenhouse gases. These returning waves of infrared radiation warm the troposphere and the earth’s surface once again.) (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [IPCC].)

Current estimates are that the earth’s warming is accelerating, and climate models predict that the average surface temperature will rise by 2.4 to 6.4°C by the year 2100.

The direct effects of climate change on human health include heat-related illnesses and deaths; the impacts of increased floods and droughts (often followed by malnutrition due to loss of cropland); the spread of infectious diseases to wider geographical ranges, both in latitude and altitude as mosquito-borne illnesses such as West Nile virus, tick-borne illnesses such as Lyme disease, and rodent-borne illnesses such as hantavirus follow the warming trends; a longer seasonal duration of biogenic allergens; cardiorespiratory problems due to increased ground-level ozone concentrations; increase in water-related diseases as water scarcity leads to freshwater contamination; algal blooms with associated cholera outbreaks; increased outbreaks of cryptosporidiosis due to heavy rainfall; and the threat to human health and well-being by the more violent storms associated with warming.

The indirect health effects include water scarcity, with the number of people living in water-scarce countries expected to rise six-fold from 470 million to 3 billion between 1990 and 2025; nutrition deficits driven by a drop in crop yields combined with increased demand due to population growth and higher levels of consumption as affluence promotes shifting to a meat-based diet; undernutrition (indicated by stunting and underweight in children under 5 years) due to lowered crop yields; decreased nutritional content of grains due to increased atmospheric CO2 concentrations; and finally population displacement—with associated immune system challenges, infectious diseases, housing and sanitation challenges, lack of safe drinking water, malnutrition, violence, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

The leaching into groundwater of industrial chemicals such as pesticides and herbicides and into the air of substances such as dioxin due to incineration of medical waste has led to an accumulation of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) in the human body. Almost all humans have residues of these chemicals in their tissues, and there is increased concern among public health officials that these levels could reach thresholds harmful to human health. The emerging toxicological field of endocrine disruption focuses on the influence of POPs in imitating or blocking the actions of hormones, possibly leading to a variety of reproductive and neurodevelopmental disorders.

The ways in which cities grow to accommodate increased population may be contributing to worsening human health. The “built environment” refers to the impacts of urban sprawl, traffic congestion, and the associated sedentary lifestyle of the population as people spend more time in cars and in gridlock driving to work or shopping. The US CDC estimates that urban sprawl due to lack of adequate land use planning is associated with increases in obesity, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree