CHAPTER 90 Disaster Psychiatry

OVERVIEW

Disasters, especially unpredicted ones, provide fertile ground for psychiatric problems. The etymology of disaster is rooted in the Latin, dis astros (“against the stars”), words that describe both the unpredictability and the devastation of such events. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines disaster as “a severe disruption, ecological and psychosocial, which greatly exceeds the coping capacity of the affected community.” Much as trauma can overwhelm the coping capacities of an individual, disasters overwhelm neighborhoods, systems, laws, organizations, and the smooth operation of society.1 Mental health assessment and treatment in the face of a disaster must always consider the public health perspective and the impact that disruption of a community has on resiliency.

HISTORY OF DISASTER PSYCHIATRY

Disaster psychiatry arose as a subspecialty in the late 1990s in the face of increased media coverage of large-scale disasters. The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) formed a “Violence and Traumatic Stress” branch in 1991. In 1993, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) recommended that branch chapters form disaster committees. Disaster Psychiatry Outreach was founded in 1998 as an organization focused on the delivery and development of disaster psychiatry, and it held the first International Congress on Disaster Psychiatry in 2000. The Psychiatry Committee on Disasters is now a very active committee of the APA.

Current literature on disasters is often retrospective, reflective, or specific to the military.

PREPARATION FOR A DISASTER

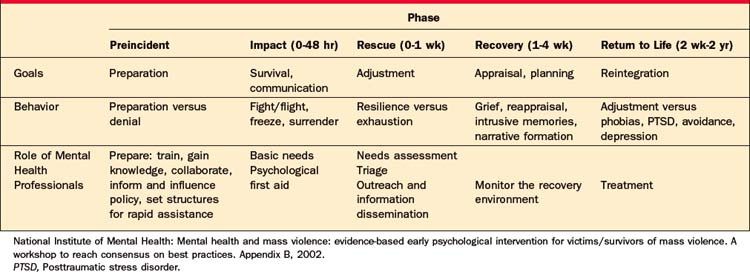

There is an inherent problem in preparing for disasters that are by definition unpredictable (both in their timing and their form). Experience with disasters teaches that despite our level of preparedness, an approach that is flexible, creative, and has the capacity to adjust and to react to an unstable and changing milieu is crucial to a successful disaster response. Disaster responses are more likely to be efficacious if they are organized and understand the goals of disaster psychiatry and how those goals shift according to the phase of the disaster. Tables 90-12 and 90-23 (created by the NIMH consensus) outline the organization of disaster responses, with attention to the broad scope of interventions.

Table 90-1 Key Components of Early Intervention after a Disaster

| Issue Addressed | Sample Activities |

|---|---|

| Basic needs | Provide survival, safety, and security |

| Provide food and shelter | |

| Orient survivors to the availability of services/support | |

| Communicate with family, friends, and community | |

| Assess the environment for ongoing threats | |

| Psychological first aid | Protect survivors from further harm |

| Reduce physiological arousal | |

| Mobilize support for those who are most distressed | |

| Keep families together and facilitate reunions with loved ones | |

| Provide information and foster communication and education | |

| Use effective risk communication techniques | |

| Needs assessment | Assess the current status of individuals, groups, and populations and institutions/systems |

| Ask how well needs are being addressed, what the recovery environment offers, and what additional interventions are needed | |

| Rescue and recovery environment observation | Observe and listen to those most affected |

| Monitor the environment for toxins and stressors | |

| Monitor past and ongoing threats | |

| Monitor services that are being provided | |

| Monitor media coverage and rumors | |

| Outreach and information dissemination | Offer information/education and “therapy by walking around” |

| Use established community structures | |

| Distribute flyers | |

| Host Web sites | |

| Conduct media interviews and programs and distribute media releases | |

| Technical assistance, consultation, and training | Improve capacity of organizations and caregivers to provide what is needed to reestablish community structure |

| Foster family recovery and resilience | |

| Safeguard the community | |

| Provide assistance, consultation, and training to relevant organizations, other caregivers and responders, and leaders | |

| Fostering resilience and recovery | Foster, but do not force, social interactions |

| Provide coping skills training | |

| Provide risk-assessment skills training | |

| Provide education on stress responses, traumatic reminders, coping, normal versus abnormal functioning, risk factors, and services | |

| Offer group and family interventions | |

| Foster natural social supports | |

| Look after the bereaved | |

| Repair the organizational fabric | |

| Triage | Conduct clinical assessments, using valid and reliable methods |

| Refer when indicated | |

| Identify vulnerable, high-risk individuals and groups | |

| Provide for emergency hospitalization | |

| Treatment | Reduce or ameliorate symptoms or improve functioning via |

| • Individual, family, and group psychotherapy | |

| • Pharmacotherapy | |

| • Short- or long-term hospitalization |

National Institute of Mental Health: Mental health and mass violence: evidence-based early psychological intervention for victims/survivors of mass violence. A workshop to reach consensus on best practices. Appendix A, 2002.

SYSTEMS

This is not a simple task. Rousseau4 and others have described how the formation of disaster plans is often abandoned because of the overwhelming complexity of the task. But it is essential that a plan to address mental health needs define itself within a network of disaster responses and goals that include safety, medical treatment, shelter, nutrition, transportation, distribution of clothing (and other necessities), location of individuals and families, and provision of accurate information about ongoing disaster and safety plans.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree