CHAPTER 93 International Psychiatry in the Twenty-First Century

OVERVIEW

A new focus for international health has recently emerged. To quote former Director General of the World Health Organization (WHO), Dr. Gro Brundtland, “Not only how people are dying but how they are living becomes a key ingredient in any international health planning.”1 Moreover, outgoing United States Surgeon General David Satcher wrote in 2001 that the time for global mental health had surely arrived.2 One reason for this new focus was the development of an important research measure called the disability adjusted life years (DALYs) measure. The DALYs measure refers to the sum of years of life lost because of premature death in the population versus the years of life lost because of disability for incident cases of the health condition in question. As a health measurement, it extends the concept of potential years of life lost due to premature death to include equivalent years of healthy life lost due to disability. The DALYs measure becomes an overall global burden of disease single unit of measure that can be applied throughout the world.3–5

In addition to the 13% global health burden of disease accounted for by mental illnesses, there are hidden and undefined burdens to consider.6 The “hidden burden” is reflected in social consequences that lead to unemployment, stigmatization, and human rights violations and not just in pathological findings. There is also the concept of “undefined burden,” which encompasses the negative impact that social and economic effects have on the families, friends, and communities of those who suffer from mental disorders. The potential casualties of mental illness related to dis-abilities include so-called social capital and community development.

THE COST OF MENTAL ILLNESS

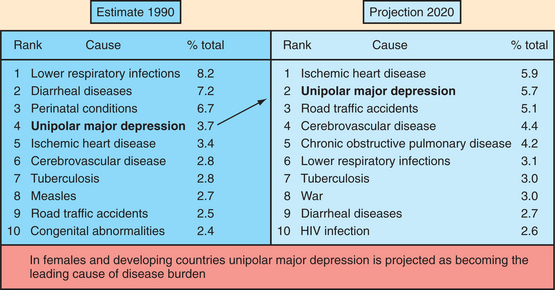

Mental illness confers extensive disability not only in wealthy countries but also in middle-income and poor countries. In addition, mental illness appears to be on the rise throughout the world. Thirteen percent of all DALYs lost in 1998 were secondary to mental illness. This includes 23% of DALYs in wealthy countries and 11% in poor countries. Major depressive disorder (MDD) is fifth on the list of the 10 leading disease causes of the global burden of disease; 5 of the 10 leading causes of the global burden of disease are mental illnesses (with alcohol abuse, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and obsessive-compulsive disorder following closely on the heels of MDD). In high-income countries, dementia is the third leading cause of neuropsychiatric burden. Moreover, mental illnesses are expected to rise to 15% of the global burden of disease by the year 2020. This would make them the second leading cause of global burden behind cardiovascular disorders (Table 93-1).7

Table 93-1 Disease Burden Measured in Disability-Adjusted Life-Years (DALYs)

|

Mental illness has increased in importance on the world public health scene for several reasons: an increased life expectancy has led to an increase in the prevalence of dementias; societal turmoil has resulted in frayed family and social bonds and to less social support; civil wars and international strife have created more refugees and cases with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD); and societal shifts toward technology and commercialization may have contributed to alienation and depression. Taken together, these factors can add up to a hostile environment for mental health.

THE PREVALENCE OF MENTAL DISORDERS

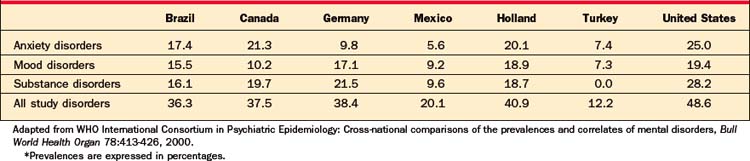

In 1990, a compilation of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule adjusted for both the International Classification of Diseases and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) nosologies, and diagnostic criteria called the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) was designed. Later, in 1998, the International Consortium in Psychiatric Epidemiology was formed by the WHO to carry out cross-national comparative studies of the prevalence and correlates of mental diseases; it proceeded to use the CIDI throughout the world (in seven regions in North America, Latin America, and Europe)8,9 (Table 93-2). Early onset of mental disorders is common, as is chronicity. This was particularly true for anxiety disorders; the median ages of onset for anxiety disorders was 15 years, while for mood disorders it was 26 years, and for substance use disorders it was 21 years. Socioeconomic measures (such as low income, little education, unemployment, and being unmarried) were all positively associated with having a mental disorder.

The International Consortium concluded that mental disorders are among the most burdensome of all disease classes. This is because of their high prevalence, chronicity, early age of onset, and resultant serious impairment. Prevention, outreach, and early intervention for people with mental disorders were recommended. The consortium called for quality assurance programs to look into the problem of inadequate treatment of mental disorders. One of these problem areas (PTSD in postconflict societies) was investigated by deJong and associates in 2001.10 PTSD was found in 37.4% of those in Algeria, 28.4% of those in Cambodia, 17.8% of those in Gaza, and 15.8% of those in Ethiopia.

ETHIOPIA AND MENTAL HEALTH IN THE DEVELOPING WORLD: AN EXAMPLE OF INTERNATIONAL MENTAL HEALTH

Ethiopia is an African country the size of Texas with a population of 75 million. Unfortunately, it has experienced a bevy of disasters (including drought, famine, human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] infection, tuberculosis, malaria, internal displacement [due to civil and border wars], and abject poverty) and other stressors and traumas. Nonetheless, there are only 17 psychiatrists in the country and only one 360-bed psychiatric hospital (Amanuel Hospital); there are no general hospital psychiatric beds in the country. These services are woefully inadequate. Fortunately, a psychiatry residency training program has been created at Addis Ababa University and in 2006, seven residents graduated (to increase the complement of psychiatrists in the nation to 17). In addition to the psychiatrists now available in Ethiopia, there are 148 practicing psychiatric nurses. Other services available include a university outpatient clinic at the Addis Ababa University and a psychiatric unit at the Armed Forces Hospital. All told, there are 45 centers in the country, each staffed by two psychiatric nurses.11

In the rural Butajira region, Awas and colleagues12 found that the prevalence of mental distress was 17.4%. Mental distress is highest in women, in the elderly, in the illiterate, in those with low incomes, in those who abuse alcohol, and in those who are widowed or divorced. Problem drinking was found in 3.7% and use of khat (cathinone, an amphetamine-like compound found in a plant and then chewed) was found in 50%.

Using the CIDI, major mental disorders in Ethiopia have a lifetime prevalence of 31.8%. Of these, anxiety is found in 75.7%, dissociative disorders in 6.3%, mood disorders in 6.2%, somatoform disorders in 5.9%, and schizophrenia in 1.8%.12

In the urban Addis Ababa region, Kebede and colleagues13 reported in 1999 that mental distress was prevalent (11.7%) in their sample of 10,203 individuals. Mental distress was most closely associated with women, the elderly, the uneducated, the unemployed, and those who had a small family. An under-reporting of mental illness in urban areas of Ethiopia may have occurred secondary to the impact of stigma, as well as governmental pressures applied at the time of the surveys. Tadesse and associates,14 in 1999, found that the prevalence of child and adolescent disorders in the Ambo district in Ethiopia was 17.7%; this is lower than the prevalence (21%) in the United States.15

By way of comparison, in the United States Epidemiological Catchment Area study, the lifetime prevalence of major mental disorders was 29% to 38%.16 Anxiety and somatoform disorders ranged from 10.4% to 25%, whereas MDD was in the range of 3.7% to 6.7%.

No discussion of mental health in Ethiopia would be complete without reference to the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) epidemic; as of 1999 in Jharma, there were 2,600,000 cases of HIV infection in the country.17 This translates into the third largest population burden in the world. The overall adult prevalence of HIV infection in Addis is between 10% and 23%. No one has carried out a study of the psychiatric co-morbidity associated with this epidemic in Ethiopia, but the prevalence of depression alone in other cohorts of HIV-infected patients ranges from 11% to 35%.

The WHO’s 2005 Atlas of Mental Health Resources noted that there was no mental health policy, no national mental health program, no community care in mental health, no substance abuse policy, and no applicable mental health law in Ethiopia.18 There were also no child mental health programs and no geriatric mental health programs. Another obvious barrier was the low number of psychiatrists and psychiatric nurses, and lack of psychologists or social workers. There is only one neurologist, but plans are underway to develop a neurology residency training program inspired by the successful psychiatry experience. Fortunately, the first draft of a mental health policy for Ethiopia has been written.

PRIMARY CARE MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES IN THE DEVELOPING WORLD

In 1974, the WHO Alma-Ata Conference established several priorities in mental health (i.e., chronic mental handicaps [including mental retardation], dementia, addictions, epilepsy, and “functional” psychoses). Remarkably, 450 million people around the world suffer from mental disorders, and a large part of the global burden of disease is due to the 25% lifetime prevalence of mental disorders. In 2001, the WHO issued the World Health Report, which focused on mental health.8 It suggested solutions to the problems of world mental health: providing treatment in primary care; making psychotropic medications available; giving care in the community; educating the public; involving communities, families, and consumers; establishing national policies and legislation; developing human resources; linking with other sectors; monitoring community mental health; and supporting more research efforts.

Based on a review of mental health intervention studies, it was believed that demonstration projects with rigorous evaluation and outcomes methodologies, and appropriate mental health service models, should be prioritized.19

THE ETHIOPIAN PUBLIC HEALTH TRAINING INITIATIVE

In 1997, the Carter Center and the Ethiopian government established the Ethiopian Public Health Training Initiative, which emerged from discussion between former United States President Jimmy Carter and Ethiopian Prime Minister Meles Zenawi. The initiative has two major objectives: to strengthen the teaching capacities of the public health colleges in Ethiopia through education of their teaching staff and to collaborate with Ethiopians to develop materials specifically created to meet the learning needs of health center personnel.

CHILD AND ADOLESCENT PSYCHIATRY

Knowledge of child and adolescent mental health problems throughout the world will be an important educational goal in the twenty-first century.20 Appreciating the stresses on children and adolescents in areas engulfed by conflict and learning about the nature of their responses provides the opportunity to learn more about resiliency and about what must be done to develop more effective programs. Even in developed countries the likelihood that a psychiatrist will see a child, adolescent, or family from a different culture has significantly increased (as a result of increased immigration and migration). Cross-cultural sensitivity is crucial to recognize differences in presentation, compliance, and acceptable interventions.

Given the enormous challenge to provide mental health care for children across the globe, Belfer20 recommended establishing regional centers of excellence. Components would include resource libraries, and access to psychiatric consultants, support, training, and clinical diagnostic functions. With these efforts a sufficient number of well-trained and culturally knowledgeable child mental health professionals could be created to treat children and adolescents and to support the healthy development of children and adolescents.

PSYCHIATRY IN AREAS OF CONFLICT

The psychological damage caused by violence, terror, torture, and rape during war and violent conflicts has not been adequately addressed or been made a priority in the field of psychiatric medicine.21 Not surprisingly, substantial research now demonstrates that mental health is a serious pro-blem among postconflict populations.22 More evidence-based research is needed to maximize the benefits of interventions (e.g., psychiatric programs and activities) for societies affected by disruptive conflicts.

Individuals (including refugees, asylum-seekers, internally displaced persons [IDPs], and illegal immigrants) directly affected by war, civil conflict, and terrorism struggle to piece their lives together after enduring unimaginable cruelty and violence. The cruel and violent acts witnessed and experienced by these individuals come in many forms; one of the most common of these is torture. Amnesty International, in its recent annual report, concluded that torture was as widespread today as when the organization launched its first global campaign in 1974 and that it is perpetrated or permitted today in more than 150 countries.1 The following sections describe and define torture (as elaborated by major existing international conventions), elucidate the major physical and psychiatric effects of torture (with an emphasis on the mental health consequences of the torture experience), and present a scientifically based and culturally valid model for the identification and treatment of torture survivors in the health care sector.

DEFINITIONS OF TORTURE

Though the word “torture” is commonly used without restraint in everyday language, its use should be clearly differentiated from words for inhumane and degrading actions that fail to match the true definition of “torture.” One of the most frequently cited definitions of torture is the World Medical Association’s (WMA’s) 1975 Declaration of Tokyo23: “The deliberate, systematic, or wanton infliction of physical or mental suffering by one or more persons acting alone or on the orders of any authority, to force another person to yield information, to make a confession, or for any other reason.”

The other frequently cited definition comes from the 1984 United Nations Convention Against Torture that expands on this definition, distinguishing the legal and political components typically associated with torture24: “Any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity.”

Types and Purpose of Torture

The most common types of torture are summarized in Table 93-3. Torturers use these techniques to achieve several goals. The major goal of torture is to break down an individual both physically and mentally to render the victim, his or her family, and his or her community politically, socially, and militarily impotent. As Mollica25 discussed in Healing Invisible Wounds: Paths to Hope and Recovery in a Violent World, humiliation is a major instrument of torture. Second, torturers seek to spread fear throughout the community or culture in which the victim lives. A single act of torture can have a devastating effect on a community (e.g., the systematic rape of women during the civil war in Bosnia).

Table 93-3 Most Common Forms of Torture

| Beating, kicking, striking with objects |

| Beating to the head |

| Threats, humiliation |

| Being chained or tied to others |

| Exposure to heat, sun, strong light |

| Exposure to rain, body immersion, cold |

| Being placed in a sack, box, or very small space |

| Drowning, submersion of head in water |

| Suffocation |

| Overexertion, hard labor |

| Exposure to unhygienic conditions conducive to infections and other diseases |

| Blindfolding |

| Isolation, solitary confinement |

| Mock execution |

| Being made to witness others being tortured |

| Starvation |

| Sleep deprivation |

| Suspension from a rod by hands and/or feet |

| Rape, mutilation of genitalia |

| Sexual humiliation |

| Burning |

| Beating to the soles of feet with rods |

| Blows to the ears |

| Forced standing |

| Having urine or feces thrown at one or being made to throw urine or feces at other prisoners |

| (Nontherapeutic) administration of medicine |

| Insertion of needles under toenails and fingernails |

| Being forced to write confessions numerous times |

| Being shocked repeatedly by electrical instrument |

From Mollica RF, Caspi-Yavin Y, Lavelle J, et al: The Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ) manual: Cambodian, Laotian, and Vietnamese versions, Torture (suppl 1):19-42, 1996.