Absence Status Epilepticus

Pierre Thomas

O. Carter Snead III

Introduction

Status epilepticus (SE) may be classified for practical purposes into convulsive SE, which must be rapidly stopped to prevent death or neurologic sequelae, and nonconvulsive SE (NCSE) in which the diagnosis is not obvious and must be confirmed by urgent EEG recording. NCSE may be further classified into nonconfusional and confusional forms.85 Nonconfusional NCSE is characterized by various somatosensory, visual, auditory, psychic, or vegetative symptoms that occur, by definition, with no impairment of consciousness. This is in contrast to confusional NCSE, which is characterized by some degree of clouding of consciousness. NCSE is also classically divided on the basis of the ictal EEG into absence SE (ASE) and complex partial SE (CPSE). CPSE is discussed in Chapter 59.

ASE, a diagnostic challenge, is a heterogeneous clinical and EEG condition that associates impaired consciousness and predominantly symmetrical bilaterally synchronous ictal discharges. On a historical perspective, Charcot, in one of his Tuesday lectures of January 1888, described a healthy 37-year-old delivery man with episodes of prolonged automatisms during which he walked from place to place throughout Paris. Charcot believed that this prolonged ambulatory fugue state was related to an epileptic breakdown of consciousness28 and later proposed a trial of potassium bromide, an early antiepileptic drug (AED).

Concept of Absence Status, Definitions, and Classification

In 1938, W.G. Lennox recorded periods of continuous spike-and-wave discharges (SWDs) and altered level of consciousness after insulin-induced hypoglycemia in one of his cousins, a child with absence epilepsy. Lennox believed that this represented very brief absences in rapid succession without a return to the usual level of consciousness and, in 1945, suggested the term petit mal status to describe this condition.99 This term implied a clinical picture limited to prolonged or serial typical absence attacks that were sufficiently close together to give rise to a prolonged disturbance of consciousness and an EEG pattern limited to the classic ictal 3-Hz spike-and-wave pattern on a syndromic absence-epilepsy background. However, it soon became clear that these forms of SE could occur in patients whose epilepsy was manifested by seizures other than absences and who had no history of idiopathic generalized epilepsy (IGE).

In the mid-1960s, Niedermeyer and Khalifeh,116 then Lob104 reported that, during ASE, the alteration of consciousness seemed to be less profound than that observed during typical absence attacks. Similarly, the EEG expression of ASE also was atypical, consisting of SWDs that were neither as regular nor as continuous as those of absence seizures. Also, these epileptic confusional states could appear in patients with severe epilepsy associated with mental retardation. These authors preferred the less specific and more descriptive term spike-wave stupor rather than petit mal status. The problems arising from the use of this latter term may explain the extraordinary development of new eponyms, described by Shorvon144 as a “nosographic labyrinth” for what were very similar clinical entities (Table 1).

Typical and Absence Status Epilepticus

In 1970, in an attempt to unify the concept, the Classification and Terminology Commission of the International League Against Epilepsy retained the term absence status, which Gastaut had proposed in October 1962 during the tenth Marseilles Colloquium60,61: “a prolonged or repeated absence seizure, thus representing SE. Clinically, ASE is essentially or exclusively characterized by impairment of consciousness of varying intensity, persisting hours to days, occasionally leading to an epileptic fugue. The EEG findings exceptionally consist of continuous or discontinuous rhythmic 3-Hz SW discharges similar to those encountered in typical absence seizures; more often one finds more or less rhythmic SW or polyspike-wave (PSW) discharges sometimes interrupted by slow background activity”.

In a further attempt at clarification, Gastaut suggested at the 1983 Santa Monica Colloquium a new classification of ASE,62 distinguishing “typical” ASE as having an excellent prognosis, occurring in patients with IGE, and characterized by a simple confusional state with rhythmic 3-Hz SWDs; “atypical” ASE is characterized as occurring mainly in patients with symptomatic and/or cryptogenic generalized epilepsy. This atypical variety could be conceptualized as a transient exacerbation of the epileptic symptomatology superimposed on a chronic epileptogenic encephalopathy, such as the Lennox-Gastaut syndrome.13 Episodes of atypical ASE were characterized by periods of confusion accompanied by more marked tonic or myoclonic manifestations, and associated with SWDs or PSW discharges slower than 3 Hz, with a variable rhythmicity and regularity.62 Moreover, these atypical ASEs were clearly distinguishable from “typical” ASE by their associated clinical features, including pseudoataxia and/or pseudodementia, their prolonged duration (several days or several weeks), their tendency to recur, and their pronounced resistance to treatment—benzodiazepines (BZ) being usually ineffective.25,40,57,122

New Cases of Uncertain Classification

During the 1970s, newly reported cases that could not be correctly classified added yet further difficulties. These events were occasionally encountered in patients with localization-related epilepsy123 and were characterized by electroencephalographic (EEG) patterns with focal features that were considered too

significant to justify their classification within the group of generalized epilepsies.59,75,115 This “imperfectly generalized” ictal pattern was compared to the focal ictal discharges of CPSE and contributed to blur the margins between the two entities. New pathophysiologic mechanisms were discussed, mainly based on the works of Tükel and Jasper in Montreal, and on depth electrode studies by Bancaud and Talairach in Paris, who demonstrated that a single epileptic focus could give rise to secondary bilaterally synchronous discharges.9,175

significant to justify their classification within the group of generalized epilepsies.59,75,115 This “imperfectly generalized” ictal pattern was compared to the focal ictal discharges of CPSE and contributed to blur the margins between the two entities. New pathophysiologic mechanisms were discussed, mainly based on the works of Tükel and Jasper in Montreal, and on depth electrode studies by Bancaud and Talairach in Paris, who demonstrated that a single epileptic focus could give rise to secondary bilaterally synchronous discharges.9,175

Several authors had indeed emphasized the similarities between these ASE forms and CPSE of temporal or, especially, frontal origin.3,59,137,168,171 These similarities are probably not fortuitous: Several reports show the transformation from CPSE with fronto-polar focal ictal discharges into an ASE with a perfectly bilateral and symmetric EEG pattern.2,97,115,139,164,168 These occasional but well-documented reports may explain the development of ASE with “generalized” discharges during the course of an extratemporal localization-related epilepsy, particularly of frontal lobe origin.97

Table 1 Absence Status Epilepticus: Some Published Synonyms | |

|---|---|

|

De Novo Absence Status Epilepticus of Late Onset

A further group of patients was described in which ASE first occurred in elderly subjects with no previous history of seizures. In 1971, Schwartz and Scott141 published reports on four patients with ASE appearing “de novo” in middle-aged or elderly adults. They suggested that these cases could represent the “the extreme end of a continuum of Petit Mal epilepsy extending from childhood to middle age.”141 However, later observations show that this is not usually so. Since 1971, about 100 such patients have been described in the literature; a review is available.165 The average age of the patients is in the sixth decade, and there is a preponderance of women. Many of the subjects have preexisting psychiatric symptoms. In two thirds of the cases, the ASE occurs with a toxic or metabolic systemic disorder.166,178 Among triggering factors, psychotropic drugs appear to be prominent and were present in a series of 79 such patients.164 The ASE may occur with high doses of psychotropic drugs or with a sudden withdrawal of the medication: Several reports have emphasized the role of BZ withdrawal.45,52,83,167 A combination of factors, such as a simultaneous toxic and metabolic encephalopathy, is characteristic. These data indicate that “de novo” ASE is more often an acute symptomatic epileptic event rather than the late resurgence of a childhood absence epilepsy, and is probably best designated as “situation-related SE.”31,177

Electrographic Status Epilepticus in Coma

In recent years, several intensive care unit series tend to lump together “subtle” SE, ASE, CPSE, and EEG patterns suggestive of NCSE in comatose patients.82,96,101,138 For example, Mayer et al. included seven patients with “nonconvulsive SE” in “comatose or obtunded patients”111 and among the comatose patients studied by Towne et al.172 8% had “an EEG pattern suggestive of SE,” a pattern whose validity has been challenged by Benbadis et al.15 This conceptual extension appears to have been caused by some degree of misinterpretation in EEG findings. Prominent generalized paroxysmal activity in comatose patients is usually the expression of a severe encephalopathy of the hypoxic/anoxic type, rather than of NCSE.117 As proposed by Kaplan,87,88,89,90 the term electrographic SE in coma seems more appropriate, in its neutrality, to characterize generalized seizure activity in deeply obtunded patients with severe brain injury. Similarly, “subtle” SE,173 the extreme end of an insufficiently treated generalized tonic–clonic SE must not be confused with ASE because context of occurrence, clinical features, prognosis, and treatment are dramatically different. Severe mental confusion in ASE may express itself as catatonia,100,107 but this presentation is radically different from a comatose state.

Clinical Classification of Absence Status Epilepticus

We believe that four types of ASE may be recognized: typical ASE, atypical ASE, ASE with focal features, and “de novo” ASE of late onset. A number of cases appear to be transitional forms between these better defined clinical entities.

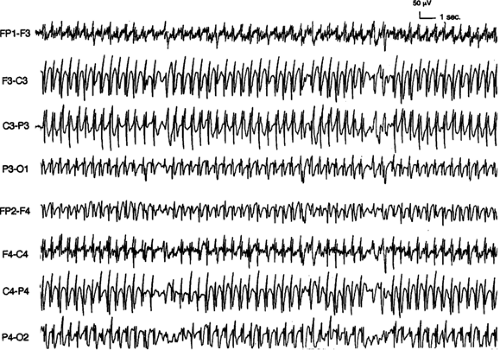

Typical ASE (Fig. 1) occurs as part of an IGE most often characterized by absences. Isolated impairment of consciousness, at times with subtle jerks of the eyelids, is the essential symptom. The EEG correlates with repetitive absence seizures and shows symmetric and bilaterally synchronous spike-and-wave or PSW complexes faster than 2.5 Hz, but this pattern is often not strictly maintained as the event continues. The immediate prognosis is excellent: An intravenous BZ injection stops the ASE.

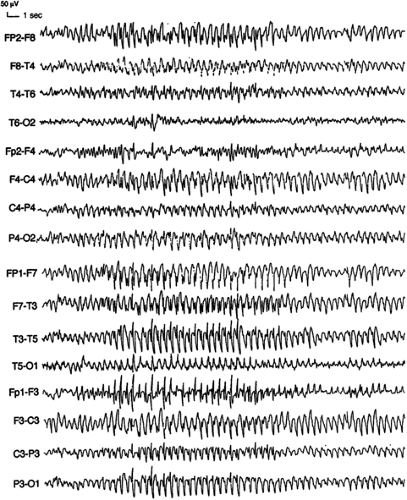

Atypical ASE (Fig. 2) occurs in patients with symptomatic or cryptogenic generalized epilepsies and is characterized by a fluctuating confusional state with more prominent tonic, atonic, myoclonic, and/or lateralized ictal manifestations than occur in typical ASE. There is often no clear-cut onset and offset of the ictus. The EEG shows continuous or intermittent diffuse irregular slow spike-and-wave or PSW complexes. The immediate prognosis is guarded, as these episodes tend to recur and to be resistant to medication.

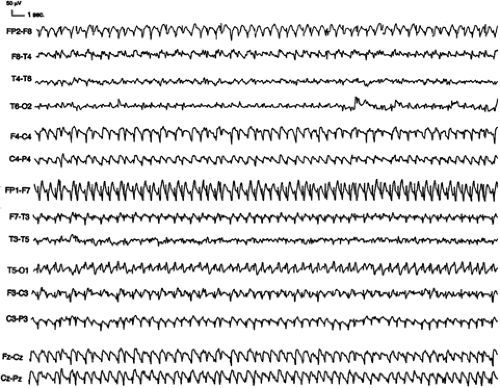

ASE with focal features (Fig. 3) occurs in subjects with a preexisting or newly developing localization-related epilepsy, most often of extratemporal origin. The EEG shows bilateral, but often asymmetric ictal discharges. Many of these cases may represent the natural evolution of CPSE of frontal lobe origin,

and the EEG may not conclusively distinguish these from ASE, especially late in the episode. The immediate prognosis is variable.

and the EEG may not conclusively distinguish these from ASE, especially late in the episode. The immediate prognosis is variable.

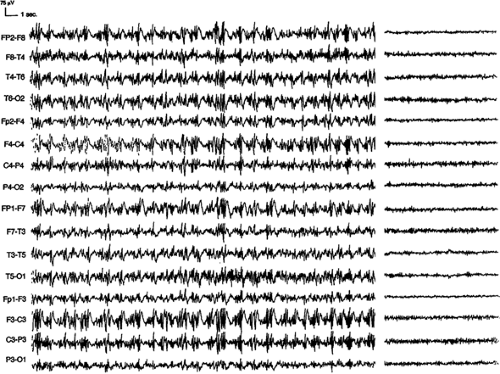

In middle-aged or elderly subjects with no previous history of attacks, “de novo” ASE of late onset (Fig. 4) is characterized by toxic or metabolic precipitating factors leading to seizures. Patients often have a history of psychiatric illness, with multiple psychotropic drug intake. The electroclinical characteristics and the immediate prognosis are variable. These episodes of ASE generally represent acute symptomatic seizures and may not recur if the triggering factors can be controlled or corrected. Long-term AEDs thus may not be needed.

Epidemiology

Lob et al.104 found that of 148 patients with ASE collected by 1962, 93% had preexisting epilepsy, and 92% of these patients had a form of IGE. Nevertheless, 16% of these patients had only absence seizures, and 11 patients had no history of epilepsy. Porter and Penry130 found that 85% of patients with ASE had preexisting epilepsy. Of the patients discussed by Rohr-Le Floch et al.137 78% had preexisting epilepsy, and all of these had IGE. Dalby35 found that 6.2% of patients with IGE had had episodes of ASE. Patients with absences more often had ASE (9.3%), than those who did not (3.4%). In patients with childhood- and adolescence-onset absence epilepsy, the incidence of ASE has varied: 3% of patients according to Cascino and Hauser,27,74 5.8% for Loiseau and Cohadon,105 9.9% for Livingston and Brown,103 28.3% for Lorentz de Haas and Magnus,106 and 37.7% for Oller-Daurella.124 A reasonable estimation is to consider that almost 10% of adults who continue to have absence seizures that began in childhood will have an episode of ASE, and that its incidence appears to increase with the frequency of absence attacks. However, with a 100 per million prevalence of absence epilepsy and a 1% occurrence of ASE in these patients, Shorvon estimated the annual incidence of typical ASE to be very low, occurring in about 1 per million persons in the general population.144

ASE has been reported in epileptic encephalopathies, such as the Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, in 15% to 40% of patients.41 Other studies13,42 show that almost all these patients have periods of epileptic confusional states at one time or another. In a mentally handicapped population, the annual incidence of ASE can be estimated to be 100 to 200 cases per million.144

Clinical Features

The cardinal clinical sign of ASE is variable clouding of consciousness, ranging from subtle subjective impairment of thought processes to severe stupor with incontinence. Subtle motor signs are seen in half the patients. In 90% of cases, the confusional symptoms fluctuate. This is an important clue in favor of the ictal nature of the confusional state, this fluctuation being most marked when the level of consciousness is well preserved. However, impairment of consciousness in ASE

is never clearly organized in a cyclic and a discontinuous way, as may be observed in some patients with CPSE of presumed amygdalo-hippocampal origin.173

is never clearly organized in a cyclic and a discontinuous way, as may be observed in some patients with CPSE of presumed amygdalo-hippocampal origin.173

Clouding of Consciousness

Although the alteration of consciousness in ASE is best represented by a continuum,6 recognition of four grades of severity in disturbance of consciousness104,136 may be useful in clinical practice. This classification was based on the largest series of ASE, the 148 cases collected at the time of the 1962 Marseilles Colloquium.60

Slight clouding of consciousness is present in 19% of cases. This consists of simple slowing of thought processes and expression, often so subtle that only the patient himself can recognize it. There is often no true mental confusion.7,129 Patients with recurrent ASE may learn to recognize these periods, which may be defined as “bad days” often described to “a lack of efficiency” or “the inability to perform at a normal level.”6 Patients with the mildest degree of disturbance have no apparent psychological disturbance and may be able to speak fluently. Although these patients are able to carry on with typical activities of daily living, they are unable to normally perform complex intellectual tasks involving choices, strategy, planning, or initiative. Formal neuropsychological testing, in one report including dichotic listening,55 may be necessary to document mild degrees of altered consciousness in ASE.118,184 Neuropsychological deficits may also suggest a more localized disturbance,65 typically with sparing of language, unlike some cases of CPSE. Shorvon144 noted the frequent and striking dissociation between these mild clinical manifestations and the impressive ictal EEG abnormalities.

Marked clouding of consciousness is most typical and is reported in 64% of cases. A frank confusional state occurs with disturbance of alertness, attention, memory, judgement, language, and with some agnosia and apraxia. The patients are severely disoriented. They are usually calm, immobile, indifferent, with little or no spontaneous language or motor activity. Simple commands are only obeyed after repeated requests, often correctly, but very slowly and after some delay. Patients usually are unable to follow more complex commands. Language is reduced to fragmented, hesitant, and at times irrelevant responses interrupted by long pauses. Echolalia and palilalia may be present. Motor tasks are performed clumsily and slowly, and sequential tasks are usually interrupted more because of attention difficulties than because of a true apraxia. Many have spontaneous or environmentally induced automatisms of variable complexity. Simple gestural automatisms are frequent. More elaborate motor patterns, which appear to represent a combination of complex automatisms and the behavioral disturbance caused by the clouding of consciousness, are associated with perseverative and compulsive features, a highly suggestive feature of ASE.

Profound clouding of consciousness is reported in 7% of cases. Even with vigorous stimulation, only very brief and limited motor or verbal responses can be elicited. The patients remain motionless, cannot move without help, and are unable to feed themselves.

Lethargic stupor is reported in 8% of cases. This resembles catatonic stupor, with apparent suspension of all psychic activity.100 Patients are motionless, with eyes turned upwards,

and incontinent of urine and stool. They are completely dependent and react only to strong painful stimulation.

and incontinent of urine and stool. They are completely dependent and react only to strong painful stimulation.

Associated Signs

Myoclonus is the most frequent and most suggestive associated sign, occurring in about half the cases.137 It is an important diagnostic clue, because as it does not occur in CPSE.137 ASE with myoclonic components could be associated with less impairment of consciousness.57 It is characterized by bilateral jerks of the eyelids or face, most often subtle and intermittent, and more easily diagnosed with the patient’s eyes closed.109 Myoclonic jerks occasionally may involve the arms and hands. These may be asymmetric, falsely suggesting a localization-related SE.136 Rarely, they may be so marked as to dominate the presentation, overlapping clinically with myoclonic SE.163,176 A history of myoclonic episodes associated with confusion can suggest a retrospective diagnosis of ASE especially in patients with preexisting IGE.78,92 Epileptic negative myoclonus may also be intermingled with the positive myoclonic jerks (Thomas, unpublished personal observation).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree