Adrenocorticotropic Hormone and Steroids

Richard A. Hrachovy

James D. Frost Jr.

Introduction

Since the 1950s, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and corticosteroids have been used to treat a variety of seizure types and epileptic syndromes. In most instances, these agents have been utilized after trials of standard antiepileptic drugs proved them to be ineffective. However, with the exception of infantile spasms, the therapeutic benefit of ACTH and corticosteroids in the treatment of disorders, such as Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, Landau-Kleffner syndrome, Rasmussen syndrome, and others, remains to be substantiated. In this chapter, the role of ACTH and prednisone in the treatment of various epileptic disorders is reviewed, and possible mechanisms by which the agents exert their antiepileptic effects are discussed.

Structure and Chemistry

Adrenocorticotropic Hormone

ACTH is a polypeptide containing 39 amino acids, the first 24 of which are required for full biologic activity. The sequence of these 24 amino acids is the same in humans and many animals, and for commercial use, ACTH is extracted from the pituitary glands of certain mammals.109 Synthetic preparations are also available commercially (typically ACTH1-24), and both forms have been used in the treatment of seizure disorders.

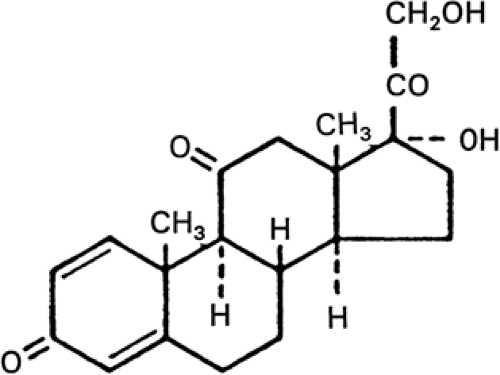

Prednisone

Prednisone is a synthetic glucocorticoid with significant anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressant effects, and only minimal mineralocorticoid properties. It is a white, odorless, crystalline powder that is formulated with several inactive ingredients for commercial use.109 The structural formula of prednisone is shown in FIGURE 1.

Basic Mechanisms of Action

The mechanisms by which ACTH and corticosteroids produce their antiepileptic effects are not known. Certain observations during the hormonal treatment of patients with infantile spasms, to the effect that only short (less than 2 weeks) courses of therapy are required in most patients to produce permanent control of seizures, suggest that the mechanism by which ACTH and corticosteroids produce seizure control, at least in the case of infantile spasms, is unlike that of traditional antiepileptic agents. One basic question has yet to be answered: Is the effect of ACTH simply related to its ability to stimulate the release of steroids from the adrenal cortex, or does ACTH work directly on the brain to produce its antiepileptic effect? Certain evidence suggests that the latter case may be true. There are several reports that ACTH may be effective in treating patients with infantile spasms whose adrenal function is suppressed.20,29,167 Also, the fact that some patients with infantile spasms who fail to respond to corticosteroids respond to ACTH and vice versa, lends support to this hypothesis.60,64 Unfortunately, the treatment of infantile spasms with ACTH fragments, which are devoid of adrenocortical stimulatory effects, has been unsuccessful.127,166

Some of the potential mechanisms by which ACTH and corticosteroids may produce their antiepileptic effects are summarized below.

ACTH and corticosteroids regulate brain growth and metabolism. Glucocorticoids and ACTH have been reported to accelerate the growth of neuroblasts in culture.129,135 ACTH accelerates myelination125 and stimulates RNA and DNA synthesis,3 and both ACTH and steroids induce various enzymes of the central nervous system (CNS). For example, corticosteroids stimulate the sodium-potassium exchanger (or Na+/K+ATPase) in the developing cerebral cortex of the kitten.68 Recent studies using highly sensitive gene expression profiling techniques (including DNA microarrays) have, for example, identified over 200 corticosteroid-responsive genes in the rat hippocampus alone, and these have included genes known to be involved in cell adhesion, growth promotion, axogenesis, synaptogenesis, and signal transduction.165 Animal studies have demonstrated that corticosteroids upregulate basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF)-2 gene expression in various brain regions. This neuropeptide has been shown to have widespread neurotrophic effects (on neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes) that regulate differentiation and function of the CNS, and it also appears to have neuroprotective activity that may facilitate recovery from injury.114 In a human study, ACTH treatment of patients with infantile spasms was associated with increased levels of β-nerve growth factor (NGF) in patients who had a good response to therapy,141 suggesting that steroid modulation of NGF gene activity may be one factor underlying the efficacy of hormonal therapy. ACTH therapy for infantile spasms has also been shown to result in significant increases of serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) lactate and pyruvate levels, with the most pronounced changes observed in patients who responded favorably to therapy,113 suggesting that ACTH-induced alteration of pyruvate metabolism may contribute to its therapeutic effect. Because of these diverse effects of ACTH and corticosteroid therapy on CNS development and metabolic function, hormonal modulation of such physiologic events at a critical stage of brain maturation is one of the most commonly proposed hypotheses concerning the mechanism of action of these agents in infantile spasms.135

ACTH and corticosteroids have direct anticonvulsant effects. In animal models, ACTH has both pro- and anticonvulsant effects. In young rats, ACTH has been shown to have a proconvulsant effect, reducing the threshold for minimal clonic electroshock seizures. However, in adult rats, ACTH increases the threshold for electroshock seizures, and moderate to high doses of ACTH delay seizure kindling.129 Corticosteroids have been shown to reduce hippocampal excitability in vitro.163

ACTH and corticosteroids modulate various neurotransmitter systems. ACTH and related peptides have been reported to increase or decrease γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and dopamine D2 receptor sites, reduce serotonin 5-HT2 sites in cortex, and increase β-adrenergic receptor binding in cortex.27,130 The reported effects of ACTH on the metabolism of neurotransmitters have been variable. In developing animals, ACTH treatment did not alter whole-brain levels of 5-hydroxytoptamine, 5-hydroxyindolacetic acid, dopamine, dihydroxyphenylacetic acid, homovanillic acid, or glutamic acid decarboxylase,72 whereas in adult rats, the effects of ACTH treatment on the levels of dopamine, norepinephrine, acetylcholine, serotonin, and GABA have ranged from no effect to increased turnover to increased synthesis.130 Corticosteroids have been shown to increase the activity of GABA79 and to block 5-hydroxytryptophan–induced myoclonus in animals.81

Dysfunction of certain neurotransmitter systems, most commonly the serotonergic and adrenergic, has been suggested as the pathophysiologic mechanism underlying infantile spasms.56 However, investigations of the levels of CSF metabolites of these and other neurotransmitters in patients with infantile spasms have been inconclusive, as have studies of the effects of hormonal therapy on neurotransmitter metabolite levels.56,130 Also, attempts at treating patients with infantile spasms using antiserotonergic and antiadrenergic drugs have not been highly successful.58,59

Thus, although ACTH and corticosteroids are known to modulate various neurotransmitter systems, the significance of these neuromodulatory influences in relation to the antiepileptic effects of these agents remains unknown.

ACTH and corticosteroids suppress the immune system. It has been a longstanding hypothesis that an immunologic defect might be the mechanism underlying infantile spasms.56 Several immunologic abnormalities have been reported in patients with infantile spasms, including antibodies to brain tissue in sera,115,133 increased numbers of activated B cells and subsets of T cells in sera,66 and an increased frequency of the human leukocyte antigen (HLA).54,65,159 However, a definite link between the immune system and infantile spasms has not been established.

A dysfunction of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis exists. Several studies have identified reduced CSF levels of ACTH6,7,28,117,118 and cortisol6 in infantile spasms patients. Considering the known effectiveness of ACTH and corticosteroids in this disorder, these findings suggest a possible role for the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis in the pathogenesis of infantile spasms. Baram and her colleagues4,7,10 have hypothesized that the basic abnormality underlying infantile spasms is stress-induced production of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) early in life. The presence of elevated CRH levels produces permanent excitatory changes in brainstem circuits, which become the region from which spasms originate. The efficacy of ACTH and corticosteroids is thought to be related to their ability to downregulate CRH synthesis. However, although CRH has been shown to produce seizures in developing animals, the seizures and interictal electroencephalogram (EEG) features of these animals are not typical of those associated with infantile spasms.7 Furthermore, elevated CSF levels of CRH have not been found in infantile spasms patients,7 and treatment of infantile spasms patients with α-helical CRH, a competitive antagonist of CRH, has not proven beneficial.5 Therefore, the applicability of this model to infantile spasms is doubtful.

Pharmacologic Fundamentals

Adrenocorticotropic Hormone

Although ACTH is available as a lyophilized white amorphous solid that may be reconstituted with sterile water for injection, repository ACTH injection (ACTH in a solution with partially hydrolyzed gelatin) is usually used in the treatment of patients with seizures. Following intramuscular administration of repository ACTH, the drug is absorbed during a period of 8 to 16 hours. In healthy adults, subcutaneous administration of 80 U of repository ACTH produced peak plasma concentrations of 17-hydroxycorticosteroids in 3 to 12 hours, and baseline concentrations were attained in 10 to 25 hours.109 In most normal adults, maximal adrenal stimulation is attained after infusing 1 to 6 U of ACTH intravenously during a period of 8 hours. More cortisol is secreted with a fixed dose of ACTH if the drug is slowly given intravenously or if ACTH is given intramuscularly as the repository injection.109 The study of Hrachovy et al.63 on the effects of ACTH on serum cortisol levels in patients with infantile spasms showed no difference in maximal serum cortisol levels attained between patients receiving 20 U/day of repository ACTH and those receiving 30 or 40 U/day.

In the blood, ACTH is transported with Cohn protein fractions II and III. The precise distribution of the drug is not known, but it is rapidly removed from the plasma by many tissues.109 Although the precise metabolic fate of ACTH is not known, circulating ACTH may be enzymatically cleaved at the 16-17 lysine–arginine bond by the plasmin-plasminogen system.109 The half-life of ACTH in plasma is about 15 minutes.50

Prednisone

Prednisone is well absorbed following oral administration, and peak serum concentrations are seen 1 to 2 hours following oral administration.22 Prednisone is 70% protein-bound,14 and prednisolone, the primary metabolite of prednisone, is nonlinearly bound to transcortin and albumin.33 The volume of distribution of prednisone is approximately 1 L/kg.42 After oral dosing with either prednisone or prednisolone, the plasma concentration-time profiles are superimposable. A first-pass exposure to liver enzymes after oral administration of prednisone facilitates the establishment of an equilibrium between prednisone and prednisolone before they reach the systemic circulation.33 The serum half-life of prednisone following a single oral dose of the drug is 2.6 to 3 hours.22,31 The biologic half-life (duration of action) is between 12 to 36 hours.50

Adverse Effects

Dose-Related Effects

Although the side effects of hormonal therapy in epileptic patients have not been studied systematically, complications of treatment depend on the size of the dose and duration of treatment. Most of the data concerning side effects of ACTH and corticosteroid therapy in epileptic patients have been collected from patients with infantile spasms.

Hypertension

Hypertension develops in 4% to 33% of patients with infan-tile spasms who are treated with ACTH or corticoster-oids.36,61,64,137 Evidence suggests that hypertension occurs more commonly in patients treated with higher doses.61,137 Hypertension, if it develops following initiation of hormonal therapy, can be treated by reduction of dose, salt restriction, or use of antihypertensive medications.

Immunosuppression

A variety of infections have been reported to occur in patients treated with ACTH and corticosteroids, including pneumonia, septicemia, urinary tract infections, gastroenteritis, ear infections, candidiasis, and encephalitis.17,21,43,61,91,96,99,137,139,146 Pneumonia is one of the most commonly occurring infections and may result in death. Thus, the preexistence or development of a respiratory tract or other infection is sufficient reason to delay or discontinue hormonal therapy.

Electrolyte Abnormalities

Hypokalemia may occur rarely in patients with infantile spasms receiving hormonal therapy.43,61,95,99,139,140 This side effect is usually seen in patients receiving higher doses and longer durations of hormonal treatment.61,99 Electrolyte disturbances have also been reported to occur more commonly in patients receiving synthetic ACTH.19

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

Echocardiographic studies have shown that evidence of myocardial hypertrophy develops in 72% to 90% of patients with infantile spasms who are treated with ACTH.2,9,88,95,132,136,158 These echocardiographic changes are reversible within months after discontinuation of ACTH therapy. It has been suggested that this myocardial change may be secondary to arterial hypertension, hyperinsulinism, and a direct effect of ACTH on myocardial cells or thickening of the myocardium, which is due to increased interstitial edema caused by increased sodium and water content.88,95

Brain Abnormalities

Studies using computed tomography (CT) and magnetic reson-ance imaging (MRI) have revealed that brain “shrinkage” may develop in patients with infantile spasms who are treated with ACTH and corticosteroids.12,39,46,51,53,71,84,86,94,101,102,105,122,145,148,172 This phenomenon reportedly reverses on discontinuance of therapy; however, in several studies39,71,106,122 the shrinkage was not reversible in 12% to 44% of patients. A variety of explanations have been suggested for these CT changes occurring during hormonal therapy including communicating hydrocephalus, loss of water, inhibition of brain growth, and alterations in the blood–brain barrier.36,39 Intracranial hemorrhage, probably secondary to arterial hypertension, has been rarely reported in patients with infantile spasms treated with hormonal therapy.137 Subdural effusion or subdural hematoma also occurs rarely.46,70,71,122,145

Eye Abnormalities

Long-term steroid therapy may be associated with the development of posterior capsular cataracts. This side effect was not observed by Hrachovy et al.60,61,62,63,64 in patients with infantile spasms treated with ACTH or prednisone; some of these patients were given formal ophthalmologic examinations, including slit lamp examinations before, during, and following hormonal therapy. Elevated intraocular pressure was reported in a small number of patients with infantile spasms treated with high-dose corticosteroid therapy.35 The elevated intraocular pressure was controlled with antiglaucoma medication.

Gastrointestinal Disturbances

Genitourinary Disturbances

Nephrocalcinosis has been reported in small numbers of patients with infantile spasms receiving ACTH and cortico-steroids. This adverse effect has been found at autopsy140 and using imaging studies.131

Osteoporosis

Weight Gain and Cushingoid Features

Irritability and Behavioral Changes

Irritability and other behavioral changes (e.g., sleep disturbance) have been reported to develop in 33% to 85% of patients with infantile spasms treated with ACTH or corticosteroids.16,18,25,45,61,99,137,153,154,164

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree