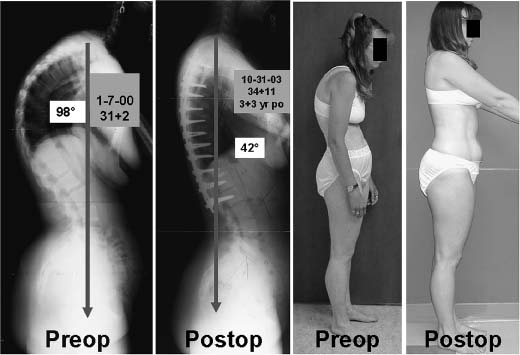

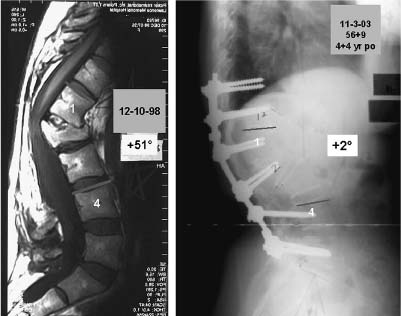

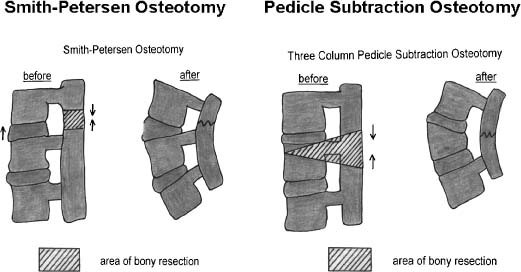

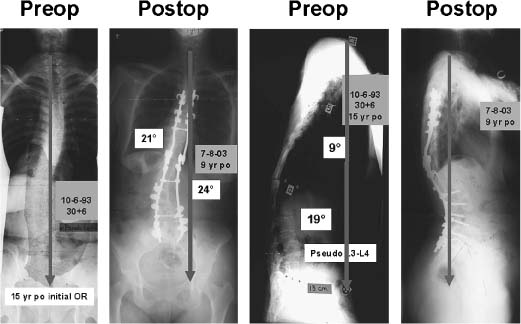

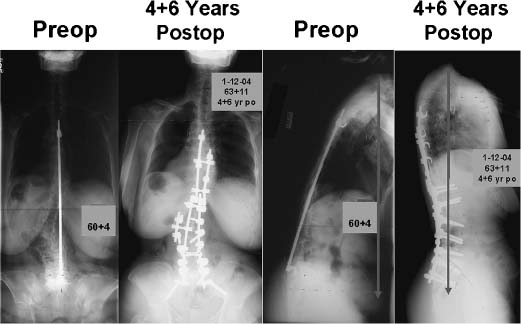

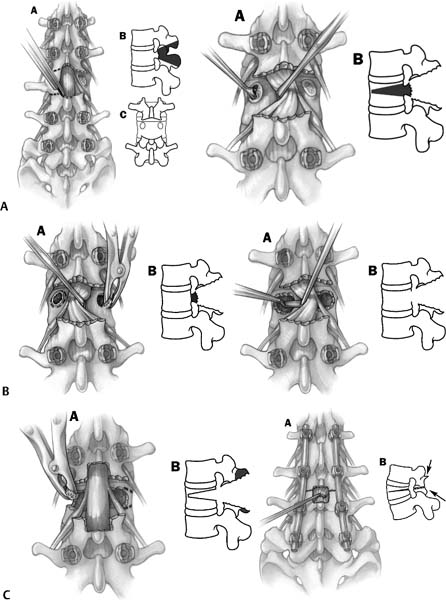

Chapter 23 The problems that commonly lead to revision surgery in the adult spinal deformity patient include (1) sagittal imbalance, (2) coronal imbalance, (3) combined imbalance, (4) pseudarthrosis, (5) infection, (6) marked degeneration distal to a fusion, (7) marked degeneration proximal to a fusion, and (8) implant failure or pullout, especially at L5 and the sacrum. It is often debatable whether to perform revisions procedures in 1 or 2 days.1,2 It is certainly possible to perform anterior and posterior surgery in the same day/same anesthesia. Decisions on 1 day versus 2 days usually center on issues of total blood loss and the time required to complete the procedure. At times, if performing one side of the spine has a substantial neurologic risk, it may be beneficial to perform that side first and be absolutely certain that the patient is neurologically intact before proceeding with the second stage. Although neurophysiologic spinal cord monitoring is quite helpful, it is not 100% accurate. If staging is advisable, then there are many possible combinations. A posterior-posterior combination has been reported and may be useful in circumstances where there are many potential surgical surprises with the posterior exploration, and segmental posterior spinal instrumentation has to be removed (especially if it is a generation of implants that is difficult to dissemble). Also, the blood loss anticipated with an exploration procedure has to be considered. It is advisable to assume that a pedicle subtraction procedure is going to be associated with a very significant blood loss, although this is not always the case. Nutritional concerns are important for the revision patient.3–5 If a substantial revision operation is being considered, it is more likely to be complication-free if the patient is otherwise healthy. An older patient who is perhaps diabetic and perhaps a chronic cigarette smoker is likely to have a much higher risk of early and late complications. Preoperative nutritional supplementation is often useful if the patient is compliant. For staged surgeries, the preference at our institution is to perform parenteral hyperalimentation between operations. Parenteral hyperalimentation is best applied through a subclavian catheter, which we will often have inserted in the interventional radiology suite on an elective basis the day before the operative procedure. When a long day of revision surgery is being contemplated, it is quite critical that the skin incision be made early in the morning. Therein, having the subclavian catheter inserted along with verification of its correct placement in advance of the operative procedure facilitates accomplishing the surgical goals. There is a range of sagittal imbalance from no global imbalance (C7 plumb relative to L5-S1) to a slight sagittal imbalance (0 to 5 cm) to a major imbalance (5 to 15 cm) and to a very major sagittal imbalance (>15 cm). Our preference is to do Smith-Petersen6 osteotomies if we are seeing a smooth kyphosis; see Case no. 1 (Fig. 23–1). If there is a sharp, angular kyphosis then our preference is to do a pedicle subtraction osteotomy7; see Case no. 2 (Fig. 23–2). For the slight global sagittal imbalance from 0 to 5 cm, consider increasing lordosis in part by doing anterior fusion with cages or fresh frozen femoral rings at segments distal to the fusion to increase distal lordosis and also consider including two to three Smith-Petersen osteotomies in the midlumbar spine without any anterior surgery. Usually, Smith-Petersen osteotomies will accomplish 10 degrees of correction per level. For a moderate imbalance from 5 to 15 cm, consider three or more Smith-Petersen osteotomies or a pedicle subtraction procedure8–11 (Fig. 23–3). Currently, our preference is the pedicle subtraction osteotomy. We can usually accomplish 10 to 15 cm of correction of the C7 plumb and 35 degrees of correction of kyphosis with this procedure.12,13 It heals predictably if performed through a fusion mass; see Case no. 3 (Fig. 23–4). Figure 23–1 Case no. 1: A young adult female presented having had previous surgery for Scheuermann’s kyphosis. She initially had a 75-degree kyphosis. She was treated with thoracoscopic releases and anterior fusion at multiple levels and then posterior instrumentation and fusion at another institution. There were problems with the implants posteriorly, so her initial operating surgeons removed those implants. After removal of the implants, her kyphosis then progressed to 98 degrees, substantially more than preoperatively. This 98-degree kyphosis was fixed. Because it was a long sweeping kyphosis, she was treated at our institution with multiple anterior releases through a formal thoracotomy and then multiple Smith-Petersen osteotomies at all levels in the thoracic spine with pedicle screw fixation to achieve the construct that is shown. She is currently 3.5 years post-op. Figure 23–2 Case no. 2: This patient presented with a sharp angular kyphosis. She had a fracture many years ago that was treated with laminectomy and fusion in situ without instrumentation at another institution. Because of the sharp angular nature, she was treated at our institution with a midlumbar pedicle subtraction osteotomy along with fusion and instrumentation. She had evidence of breakdown of the L4-L5 disk and a substantial synovial cyst at that level. Therein, the fusion was extended to L5. She is currently 4.5 years post-op. Figure 23–3 Smith-Petersen osteotomy resects bone in the posterior column through the facet joints. This opens up anteriorly at the disk space. Pedicle subtraction osteotomy resects bone through the facet joints, the pedicles, and the vertebral body. It hinges on the anterior cortex. There is theoretically no opening anteriorly. Figure 23–4 Case no. 3: This young adult patient presented with prior surgery for idiopathic scoliosis. She was previously treated with a Harrington rod. There was pseudarthrosis at L3-L4 with some spinal stenosis at that segment. Her coronal balance was excellent. In the sagittal plane, she had very positive sagittal balance. She was treated at our institution with a multiple-level anterior release and fusion along with multiple-level posterior Smith-Petersen osteotomies. The Smith-Petersen osteotomies were performed symmetrically. This provided excellent correction of her sagittal deformity. Unfortunately, it did pitch her to the concavity. This is a risk of doing multiple Smith-Petersen osteotomies through areas of residual scoliosis and rotation. She is currently 9 years post-op. For severe imbalance >15 cm, consider combining pedicle subtraction and Smith-Petersen osteotomies; or, in certain extreme circumstances, consider two pedicle subtraction procedures. One problem with performing multiple Smith-Petersen osteotomies is that the procedure shortens the posterior column and lengthens the anterior column. Therein, if the Smith-Petersen osteotomies are performed through areas of residual scoliosis and rotation, there is a potential of pitching the patient toward the concavity even if the osteotomies are done symmetrically or somewhat bigger on the convex side. This was noted by Booth et al.14; see Case no. 4 (Fig. 23–5). We have found that pedicle subtraction procedures are helpful in patients with idiopathic scoliosis and superimposed degenerative changes, degenerative sagittal imbalance, post-traumatic kyphosis, and ankylosing spondylitis. The degenerative sagittal imbalance patients are those who start off with fusion, instrumentation, and decompression in the distal lumbar spine and then have procedures that include L4-L5 and then L3-L4, a situation of working up rather than down the spine. These patients are somewhat older, usually not as healthy as those with prior idiopathic scoliosis surgery and, therein, are more apt to have complications with their surgical revision. Figure 23–5 Case no. 4: This is a patient with prior idiopathic scoliosis surgery with fusion and instrumentation to L5. She presented to us with severe degenerative disk disease at L5-S1 and inability to stand erect. Surgical treatment at our institution consisted of pedicle subtraction osteotomy in the midlumbar spine and circumferential fusion at L5-S1 with structural support and sacropelvic fixation. Her pedicle subtraction osteotomy was done at the apex of her lumbar scoliosis, through an area of substantial rotation. The osteotomy was performed symmetrically. The sagittal correction was quite good. Note there is no problem with coronal imbalance in this case. The patient is currently 4 6 years post-op. Three major problems we have found with performing pedicle subtraction osteotomies are (1) non-union of levels added to the fusion, especially proximally if done without anterior surgery, (2) neurologic deficit, usually unilateral oneor two-level root compression not detected by somatosensory potential monitoring, and (3) proximal junctional kyphosis. For that reason, when closing a pedicle subtraction osteotomy, it is essential to watch for subluxation and to enlarge the canal centrally. Then, with a Woodson elevator feel north, south, east, and west to be sure there is no nerve root compression. See steps 1 to 6 for the performance of the pedicle subtraction osteotomy (Figs. 23–6A to 23–6C; Table 23–1). Figure 23–6 (A) A symmetrical wedge of bone is resected around the pedicles. Then the pedicles are resected part way into the vertebral body. The vertebral body is decancellated on both sides through the pedicles. (B) Next, the posterior vertebral cortex is thinned as much as possible. The posterior vertebral cortex is then green-sticked and resected. (C)

Adult Spinal Deformity Revision Surgery

♦ Reasons for Revision Surgery

Sagittal Imbalance

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree