INTRODUCTION

The term ‘ageing’ is a generalized complex terminology that can address a number of concepts, including aspects such as the demography of the whole population or trends within specific age groups (such as births or the older population). But the term ‘ageing’ is also a generic term for the older population and factors associated with it. Within this chapter we aim to investigate some of these factors and show how the population of the world has changed, how historical changes will affect health in the next decades, how our estimates of population change are challenged by diseases and treatments and what can we currently say about the health of the older population.

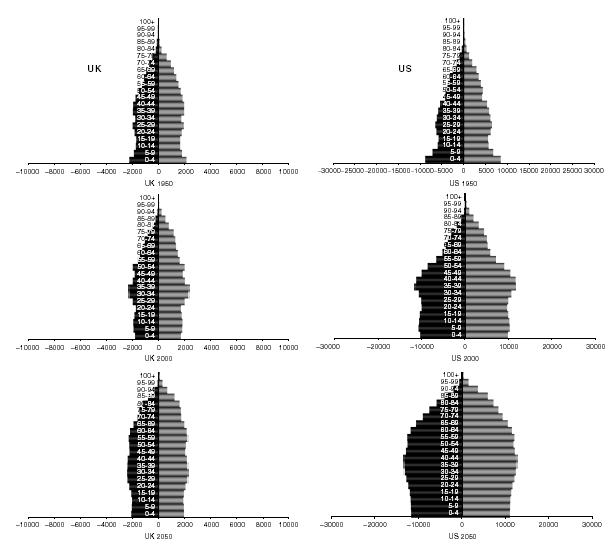

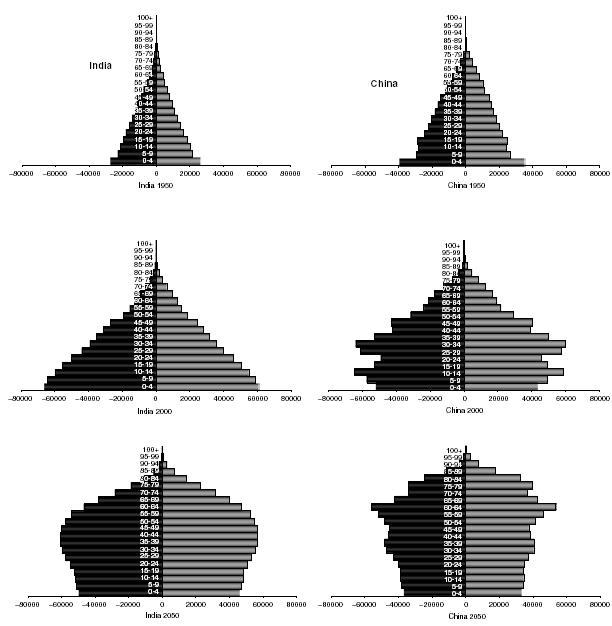

The historic, current and future population demography demonstrates historic and interesting changes. Over the course of the last 50 years and in the next 50 years there has been and will be a fundamental shift in the distribution of the human population. Different areas of the world display different demographic shift patterns; for example the shifts in the United Kingdom and United States show patterns that are different from those seen in China and India1. Nevertheless, all countries are experiencing population ageing.

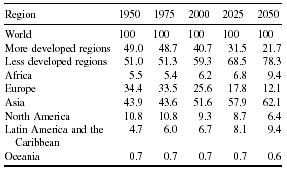

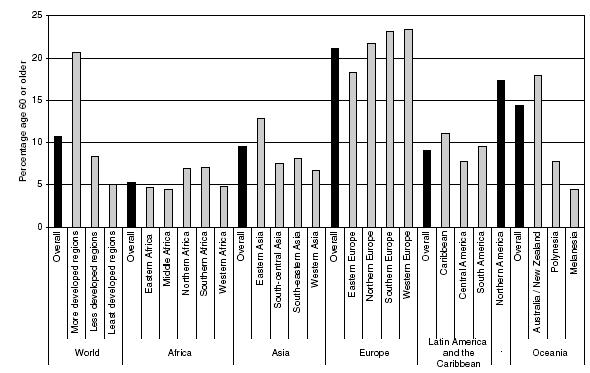

Figure 16.1 shows the demographic changes across different regions of the world. China and India have not only had a large change in the distribution of the population, they have also increased dramatically in size. The shift in this distribution means that the proportion of the population that is already considered ‘older’ varies greatly by country. Current estimates of the proportion of the population aged 60 years and over are shown in Figure 16.2. Although the relative distribution shifts from Europe and North America in 1950 towards Asia by 2050 (Table 16.1) there are large numbers in the older population throughout the whole world.

Despite these differing demographic patterns already 64% of the older population (aged 60 and over) live in developing countries and by 2050 nearly 80% of those aged 60 and above will live in developing countries2. This definition, however, includes only Europe, North America, Japan, Australia and New Zealand within the developed countries – a pattern that may not reflect true differences3.

Trends in fertility affect the composition of the older population many years later. While this ensures that surprises are not often encountered in the description of the older population it also means that demographic influences are less immediate at solving the challenges predicted. The decisions made on childbirth both between the two World Wars and after the Second World War are now shaping the composition of the older population. The generation of children to the ‘baby boomers’ in the 1960s are now reaching middle age and the size of this demographic bubble can be clearly seen in the population pyramids (Figure 16.1). Many European countries have for a number of years been below the reproductive factor (2.1 births per woman2). This rate of replacement of the younger population will again shift the relative balance of the population in terms of young and old. In this case there is a double impact, as the baby boomers reach old age with a lack of grandchildren to replace the status quo of the pyramid. This will create, at least for the next 50 years, an ageing society. The current fertility decisions of the early adults are not suggesting that this imbalance will refocus. In fact the decisions to delay or reduce childbirth across the whole of the developed population (and wider in many cases) mean that the majority of countries are now below the 2.1 factor.

In the less developed regions where infant mortality is still high, despite advances resulting from the Millennium Development Goals (UN Millennium Goal 4), the fertility rate is still relatively high but is reducing dramatically. The developing countries are still experiencing an ageing population, but in a more historically understood way, although many unknowns remain4. A recent UN report states that fertility levels are unlikely to rise again to the historic highs and therefore the expression of population ageing is irreversible5. However future population size is sensitive to small but sustained deviations from the replacement level5.

The patterns of fertility affect not only the absolute level of the future middle-aged and older population but they also have a direct impact on the life of the older population at the individual level. The number of available carers within a population is almost universally linked to the extended family support. As this family structure shifts so will the life of the older person6. An international comparative survey on the older population undertaken in 1996 showed that the proportion of the older population aged 60 and over living in threegeneration households was 29-43% in Asian countries compared with 2% for European and North American countries7. If this structure is mimicked with the changing demographic then it will impact enormously on policy.

TRENDS IN LIFE EXPECTANCY AND HEALTHY LIFE EXPECTANCY ACROSS THE AGE RANGE

There has been a steady and consistent increase in life expectancy at birth across all continents and in both males and females (Figure 16.3). However, the major issue in the statistical trends in healthy life expectancy is whether with the extension of longer life there is also an extension of healthy life (i.e. the total remaining life that can be expected to be free of disability). Three patterns of

Figure 16.1 Population pyramids and changing distribution. Bars refer to the size of the population (in thousands) of men (left) and women (right) in each age group

population change in healthy life expectancy have been proposed, an expansion of morbidity8, a compression of morbidity9 or dynamic equilibrium10. Expansion of morbidity would imply longer life expectancy but at the same time longer life expectancy in ill-health, compression of morbidity would imply that the life extension is predominantly from the healthy life and dynamic equilibrium implies that severity may change, but the burden remains constant. Evidence to date suggests that all three scenarios can occur in different populations at different times.

MEASURING THE CHANGING HEALTH STATUS OF THE OLDER POPULATION

Assessing the compression or expansion of morbidity relies on being able to measure the health status of the older population. Complementary insights regarding the changing health of the older population can be gained from several major sources, each with their own merits and drawbacks. In developed countries routinely gathered statistics such as census data and birth and death certification may be used and these provide reliable information on demographic changes. Routine

medical databases, such as hospital admissions data, prescription records or disease registers provide another source. However the reporting of medical conditions to these registers may be biased by various processes. Both the mechanisms by which older people come to the attention of health care providers and reporting practices change with time, particularly in the older population, as a result of changing awareness, attitude and perception of health both by older people and their health care providers. Reporting practices can also vary geographically. Psychiatric conditions in the older population are particularly likely to be under-reported, and death certificates often do not mention major diseases such as dementia despite it being present or a major contributing factor to the death of an older person. Using routine data to record the health and in particular the psychiatric health of the older population is therefore unreliable. Furthermore in many areas of the world such statistics are not collected routinely.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree