67 Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

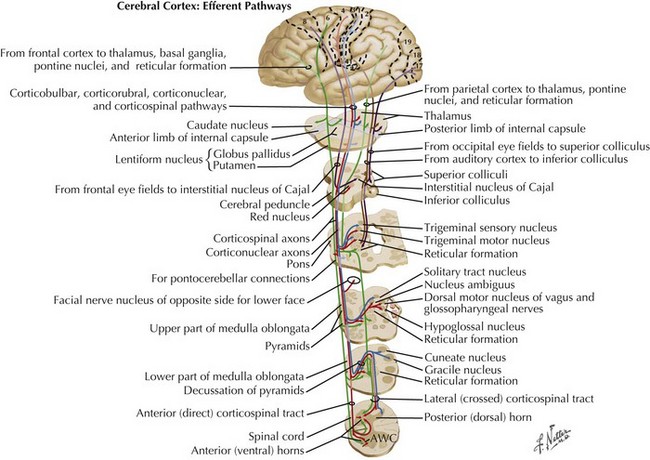

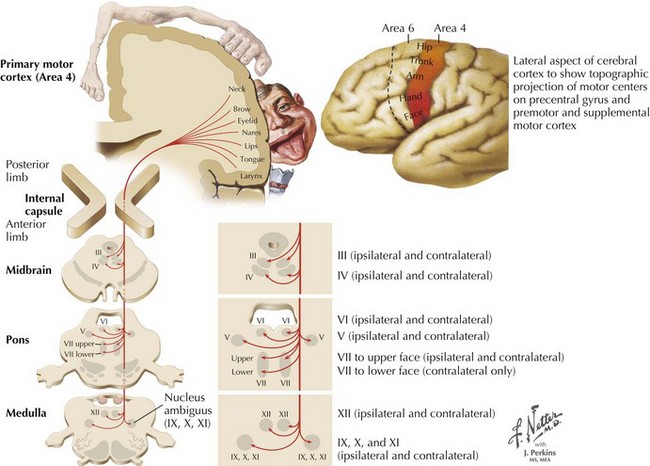

Charcot’s description was of a disorder characterized by loss of voluntary motor function, resulting from degeneration of anterior horn cells, corticospinal tracts, and motor cranial nerve nuclei and cortical motor neurons (Figs. 67-1 and 67-2). ALS is a sporadic disorder (sALS) in the majority of cases. ALS is inherited in 5–10% of cases, i.e., familial ALS (fALS), usually in an autosomal dominant fashion. In general, fALS patients have phenotypes that closely resemble sALS, although fALS may have an earlier onset. In absence of family history, the disorders are clinically indistinguishable.

Etiology, Genetics, and Pathogenesis

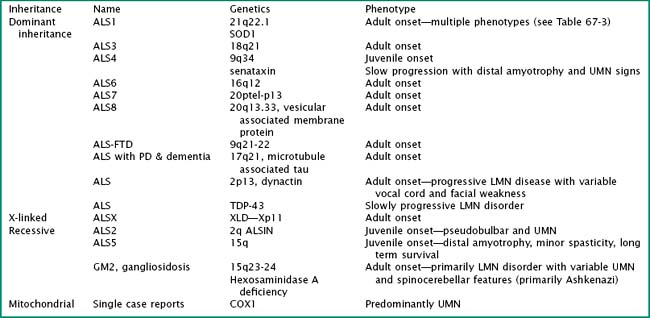

Particularly intriguing has been the recognition of the phenotypic heterogeneity in SOD1 fALS (Table 67-1). About 114 pathologic mutations have been identified within the five exons of the SOD1 gene; each of these mutations may produce a distinct phenotype. The most common mutation found in North America is an alanine for valine (A4V) substitution at codon 4; this typically produces a lower motor neuron dominant phenotype (LMN-D) with a life expectancy approximating 1 year. Table 67-1 summarizes the phenotypic heterogeneity that results from different SOD1 mutations. SOD1 mutations are not fully penetrant. It is estimated that individuals carrying the mutation have an 80% chance of developing disease by age 85 years. SOD1 mutations constitute 20–25% of all individuals with fALS. Other fALS genotypes are listed in Table 67-2. Some of these mutations produce a predominantly lower motor neuron (LMN) or upper motor neuron (UMN) disorder and more closely resemble the phenotypes of spinal muscular atrophy or hereditary spastic paraparesis, respectively.

Table 67-1 Phenotypic Variation in SOD1 fALS

| Phenotype | SOD 1 Mutation |

|---|---|

| Lower motor neuron predominant | A4V, L84V, D101N |

| Upper motor neuron predominant | D90A |

| Slow progression (>10-year survival) | G37R, G41D, G93C, L144S, L144F |

| Fast progression (<2-year survival) | A4T, N86S, L106V, V148G |

| Late onset | G85R, H46R |

| Early onset | G37R, L38V |

| Female predominant | G41D |

| Bulbar onset | V148I |

| Low penetrance | D90A, I113T |

| Posterior column involvement | E100G |

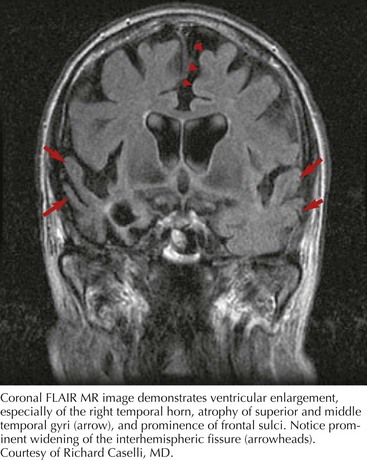

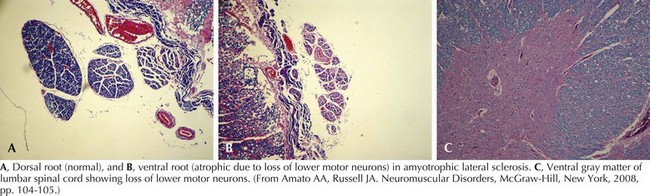

Whatever the mechanism, ALS is pathologically characterized by loss of myelinated fibers in the corticospinal and corticobulbar pathways (see Fig. 67-2) and loss of motor neurons within the anterior horns of the spinal cord and many motor cranial nerve nuclei. Even in individuals with predominantly UMN or LMN involvement clinically, pathologic involvement of both systems is seen. Patients with associated FTD have preferential lobar atrophy and neuronal loss from these portions of the brain (Fig. 67-3). As a result of anterior horn cell loss, ventral roots become atrophic in comparison to sparing of their dorsal root counterparts (Fig. 67-4). Anterior horn cell loss occurs within virtually all levels of the spinal cord with selective sparing of the third, fourth, and sixth cranial nerves, and Onuf’s nucleus within the anterior horn of sacral segments 2–4. There is also cell preservation within the intermediolateral cell columns.

Clinical Presentations

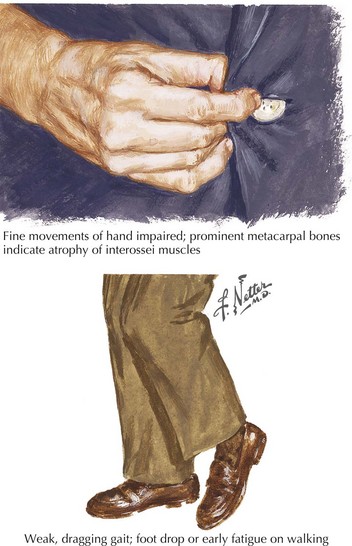

The presenting features of ALS are quite variable. Typically, the patient seeks medical care when his or her weakness begins to affect activities of daily living (Fig. 67-5). It is not uncommon for ALS to be misdiagnosed initially and the time between symptom onset and diagnosis is usually months. Unfortunately, there is a tendency to misdiagnose ALS as a potentially treatable nerve, nerve root, or spinal cord compressive syndrome or orthopedic condition. A significant percentage of ALS patients may undergo unnecessary surgeries. It should be emphasized that progressive weakness and atrophy in the absence of pain and sensory symptoms rarely represents a surgically treatable condition.

Tongue atrophy, fasciculation, and weakness are perhaps the most frequently occurring and recognized manifestations of LMN involvement of cranial nerves. It is important to observe for fasciculations when the tongue is relaxed on floor of the mouth (Fig. 67-6). Tremulousness of the tongue with attempted protrusion may be readily misinterpreted as representing fasciculations. Weakness of both facial and jaw muscles may occur in ALS but they are usually subtle. Weakness of neck extension and neck flexion is common in ALS, and head drop may be a rare presenting feature (Fig. 67-7). Neck drop is commonly associated with posterior neck discomfort and is typically relieved when the neck is supported. Notable for their absence are ptosis and ophthalmoparesis, and symptoms related to sight, hearing, taste, smell, and facial sensation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree