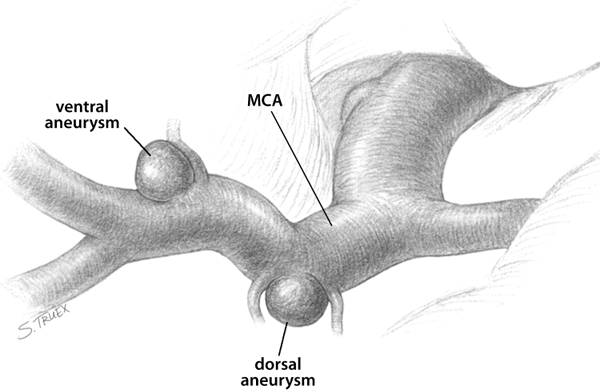

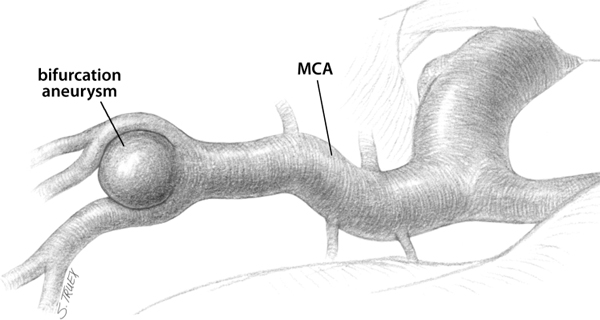

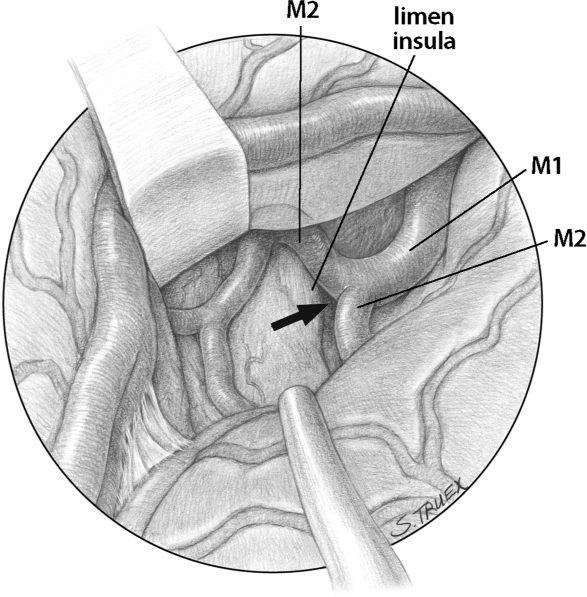

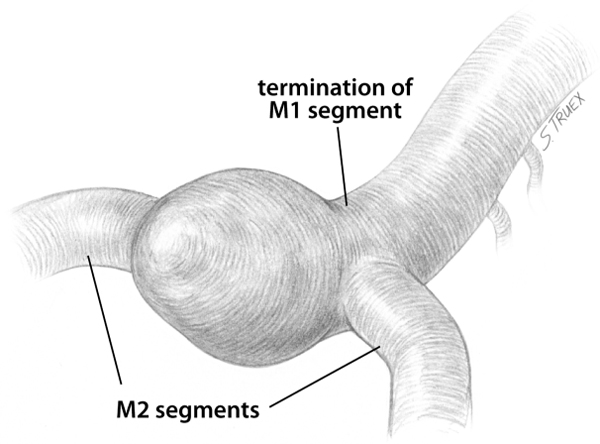

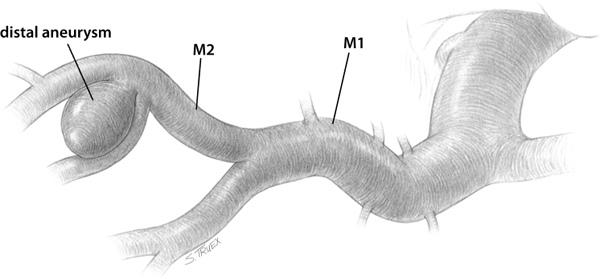

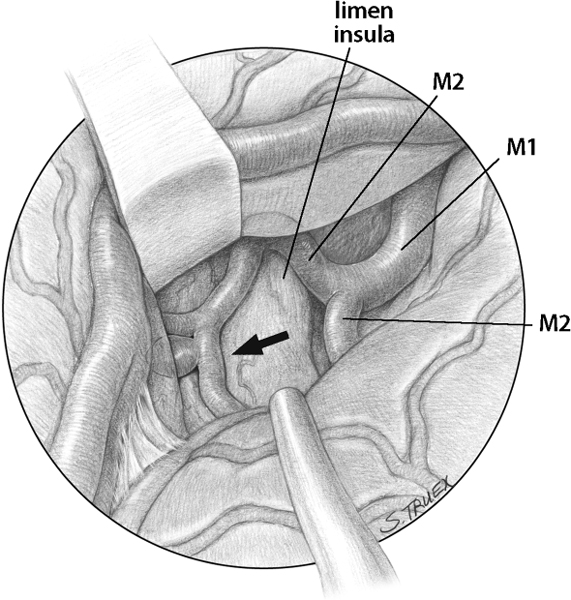

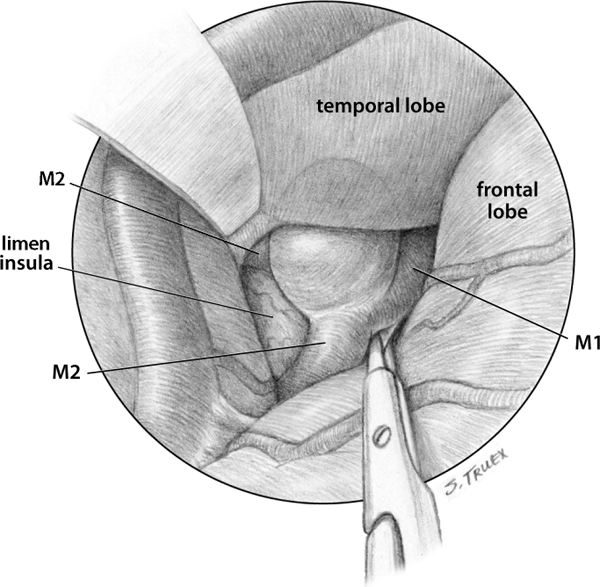

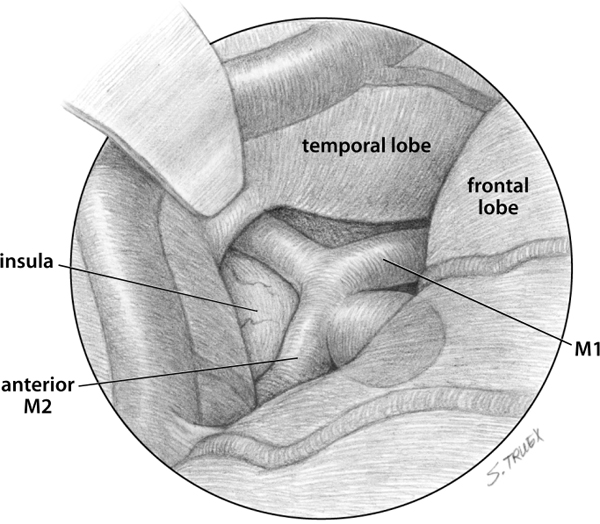

6 Aneurysms of the middle cerebral artery (MCA) represent some 15 to 25% of all intracranial aneurysms in large clinical series, being less frequent in series of ruptured aneurysms and somewhat overrepresented in series combining both ruptured and unruptured lesions. They classically occur at the main bifurcation of the MCA’s main trunk or M1 segment but not infrequently are found in association with more proximal branches (lenticulostriate and anterior temporal arteries); they may also arise distal to the MCA bifurcation, where mycotic and dissecting lesions are most common. Large and giant aneurysms occur with a disproportionate frequency along the MCA and may be of saccular, fusiform, mycotic, marantic, or dissecting origin. Subarachnoid bleeding from MCA aneurysms typically fills both the sphenoidal and insular portions of the ipsilateral sylvian fissure, with variable extension into the basal cisterns. Intraparenchymal hemorrhage occurs with greater frequency than is found in any other aneurysmal location; bleeding is typically into the overlying temporal lobe, although superiorly directed aneurysms may on occasion rupture into the frontal operculum. For purposes of discussion, these aneurysms can be divided into three separate and distinct anatomical groups: 1. Proximal MCA lesions, which arise along the M1 segment between the internal carotid artery (ICA) bifurcation and the main MCA bifurcation 3. Distal MCA aneurysms, arising in the cortical or hemispheric portion of the sylvian fissure beyond the M2 origins Proximal MCA aneurysms are found in the horizontal or sphenoidal segment of the sylvian fissure, arising along the M1 segment from either the dorsal aspect in association with the lenticulostriate arteries or the ventral aspect, usually at the site of the anterior temporal artery’s origin or at an early MCA bifurcation (Fig. 6.1). The dorsal lesions tend to be quite small and to project superiorly into the brain, and they often have a lenticulostriate branch emanating from either their medial or lateral margin. These dorsal aneurysms are not infrequently the cause of subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) and may easily be overlooked on a cursory examination of a poorly performed angiogram. Ventral aneurysms are more consistent in their size, projection, and general appearance. As a rule they have small, well-defined necks, with the entire aneurysm complex lesion lying in the subarachnoid space. Although they can produce subarachnoid hemorrhage, more frequently they are unruptured, asymptomatic aneurysms found incidentally on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or identified in the evaluation of SAH produced by a separate aneurysm, often another MCA lesion. Fig. 6.1 MCA aneurysms. By far the most common location for aneurysm formation on the MCA is the MCA bifurcation (Fig. 6.2), which is routinely situated in the lateral aspect of the horizontal segment of the sylvian fissure, immediately medial to the limen insulae (Fig. 6.3, arrow indicating MCA bifurcation). The bifurcation is almost always more proximal than the surgeon conceives it to be, meaning an exposure that opens only the cortical or hemispheric portion of the fissure is inadequate for aneurysm exposure, much less for obtaining proximal control. The M1 trunk ends in a true bifurcation in over 90% of cases; references to this division as a trifurcation are both inaccurate and misleading. Not uncommonly, the more anterior of the two M2 branches (frontal ascending trunk) divides quickly, the two M3s joining the posterior M2 (insular trunk) to make three large branches surrounding the aneurysm fundus, all of which must be accounted for at the time of clip placement. Almost invariably, the M1 segment terminates in a T-shaped bifurcation, with the M1 itself representing the long stem of the T (Fig. 6.4). The two M2 segments routinely exit the bifurcation at roughly 90-degree angles from the M1 and at 180 degrees from each other. The larger the aneurysm, the more the branches correspond to this general configuration. Even in giant lesions, when the initial millimeters of each M2 segment may actually be intramural, the branches are located on exact contralateral sides of the M1 termination, exiting the parent vessel at an angle of no more than 90 degrees and running diametrically opposite courses. Awareness of this phenomenon can be of great assistance to the surgeon, both in seeking to initially identify the exiting branches and in planning clip application. Fig. 6.2 Most common location for MCA aneurysm. Fig. 6.3 Anatomic position of MCA bifurcation. Fig. 6.4 Configuration of an MCA aneurysm. These aneurysms arise in the cortical or hemispheric segment of the sylvian fissure, distal to the main M1 bifurcation (Figs. 6.5 and 6.6, arrow indicating distal MCA). They lie on the insular cortex and, depending on their size, may invagi-nate into either or both frontal and temporal operculae. Frequently these aneurysms are more distal than expected and therefore can be difficult to expose. Smaller aneurysms in this location may be routine saccular lesions, but more frequently these aneurysms are fusiform in contour and dissecting or mycotic in etiology. As such, they may involve not solely a bifurcation or branch point but often incorporate large segments of both afferent and efferent arteries. Early recognition of the nature and anatomical extent of these lesions is critical to their successful management. Coupled with the aneurysm’s location, the projection of these lesions determines the optimal route of approach. For proximal aneurysms, it is always necessary to open the sphenoidal portion of the fissure for proximal control and aneurysm exposure. When dealing with the dorsally projecting aneurysms associated with the lenticulostriate arteries, proximal control is simple to achieve with distal to proximal opening of the sylvian fissure beginning at the MCA bifurcation; the reverse is true with ventrally projecting aneurysms in which proximal control is best obtained by careful dissection of the ICA in the carotid cistern followed by exposure of the MCA at the carotid bifurcation, prior to opening the distal aspect of the fissure. Fig. 6.5 Distal MCA aneurysm. Fig. 6.6 Anatomic position of distal MCA aneurysm. For the common aneurysms at and near the M1 bifurcation, the critical aspect of their projection relates to the axis of the parent MCA. If the aneurysm’s projection is inferior to the M1 (Fig. 6.7) the surgeon can first open the hemispheric portion of the fissure, identifying the M2 branches and following them retrograde to the bifurcation. Then, by hugging the cortical surface of the limen insula on the anterior aspect of the aneurysm’s neck and dissecting medially into the fissure, the M1 segment can be safely identified. When dealing with these inferiorly projecting lesions there is no necessity to open the sylvian fissure proximally to obtain proximal control. On the other hand, if the aneurysm in question projects superiorly rostral to the axis of the M1 segment (Fig. 6.8), the sphenoidal portion of the sylvian fissure should be opened initially to secure the M1 segment, prior to exposure of the more laterally located aneurysm. A safe way to accomplish this is to begin the fissure dissection laterally at the junction of the sphenoidal and hemispheric portions, deepen the exposure until the base of the aneurysm is seen, and then carry the dissection medially, opening the horizontal segment fissure from lateral to medial for ~2 cm. The frontal and temporal operculae should be completely separated superficially along the sphenoid ridge and then gently retracted to expose the M1 lateral to the lenticulostriate origins and medial to the bifurcation, an optimal site for temporary arterial occlusion if necessary. Fig. 6.7 Inferior projection of MCA aneurysm. The relatively rare and unusual distal MCA aneurysms are, by definition, located completely within the hemispheric segment of the sylvian fissure. If the MCA bifurcation is not involved, proximal control of the M2 trunks can be obtained by initially opening the fissure at the junction of the sphenoidal and hemispheric portions, and then the aneurysm is exposed by carrying the dissection as distally as the size and anatomy of the lesion dictate. Because of the complexity of these aneurysms and the consequent difficulties with their effective treatment (complex clip reconstruction, distal bypass, branch reimplantation, etc.), it’s almost impossible to expose too much of the distal M2 and M3 branches. Fig. 6.8 Superior projection of MCA aneurysm.

Aneurysms of the Middle Cerebral Artery

General

Anatomy

Proximal Middle Cerebral Artery Aneurysms

Middle Cerebral Artery Bifurcation Aneurysms

Distal Middle Cerebral Artery Aneurysms

Projection

Procedure

General

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree