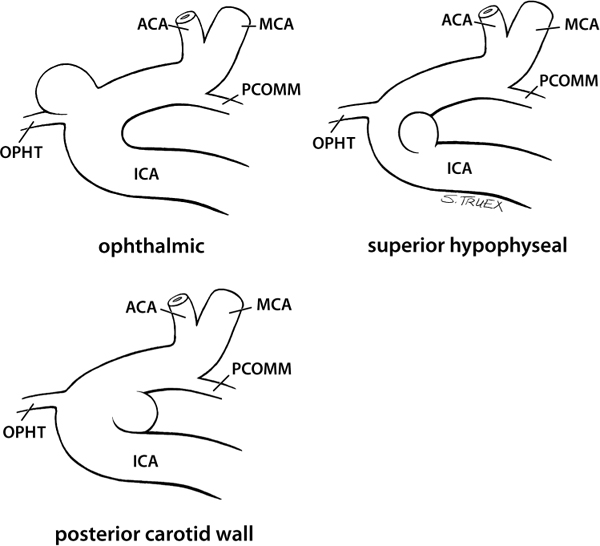

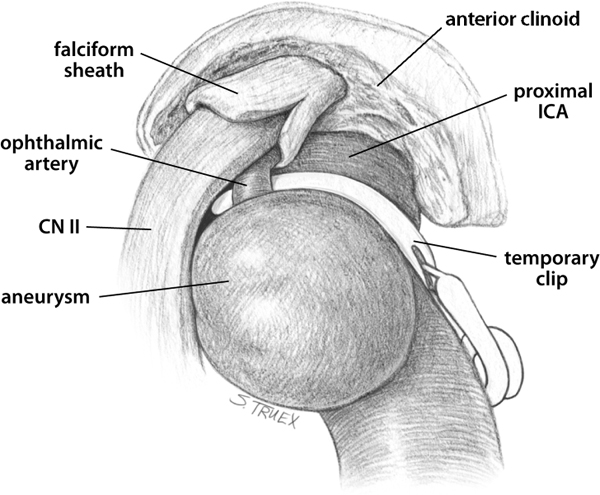

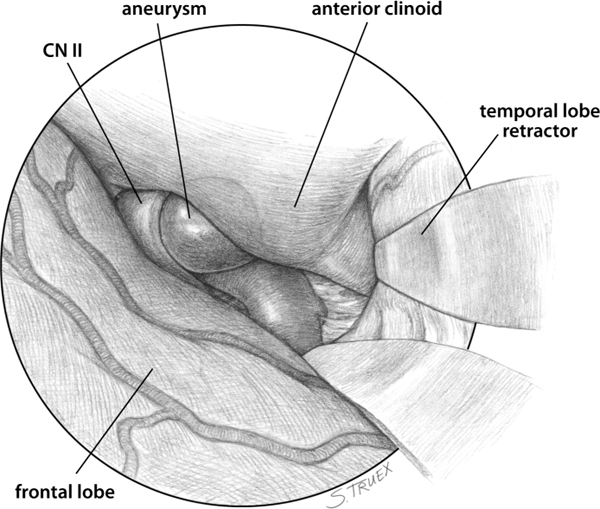

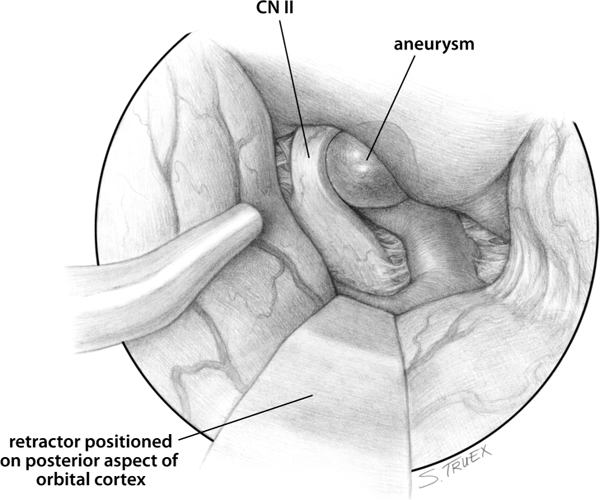

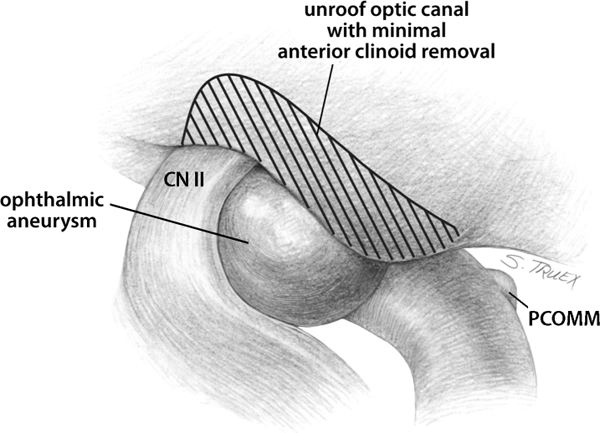

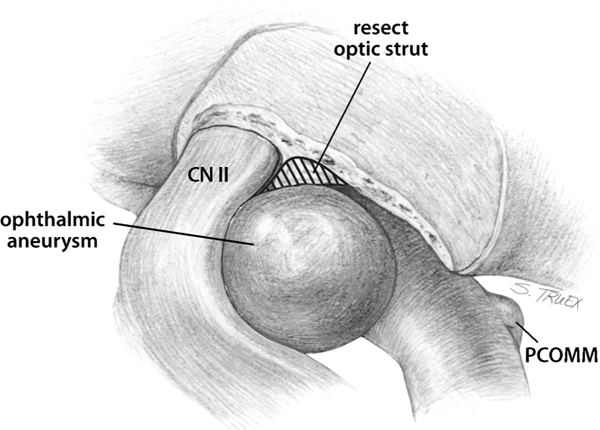

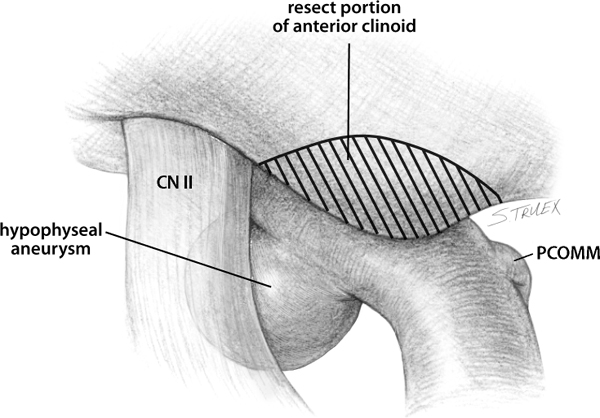

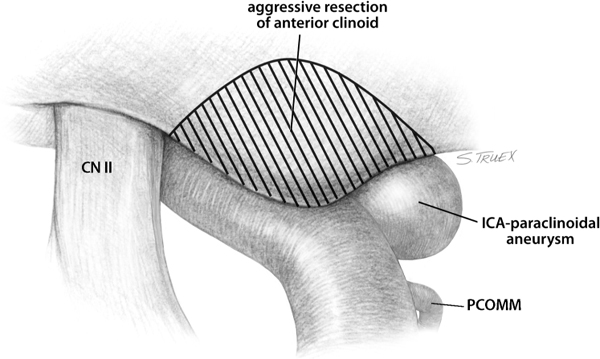

4 The nomenclature of these aneurysms, which emerge from the parent artery at or near its entry into the subdural space, is varied; however, surgeons agree that there are three separate and distinct common sites of origin. In order of frequency, these are the origin of the ophthalmic artery (OPHT), the origin of the superior hypophyseal artery, and the posterior carotid wall proximal to the origin of the posterior communicating artery (PCOMM). For the sake of discussion, we will label these aneurysms internal carotid artery (ICA)-OPHT, ICA-superior hypophyseal, and ICA-paraclinoidal (Fig. 4.1). The problems common to the treatment of these three varieties are discussed initially, followed by a brief consideration of the features unique to each distinct aneurysm site. The two common issues that complicate the treatment of this group of aneurysms are very straightforward: (1) proximal control and (2) complete aneurysm exposure. Both of these issues are directly related to the lesion’s location, which is buried in the structures of the skull base. Over the past decade and a half, the development of innovative “skull base” approaches has proven that with the expenditure of sufficient time and effort, any reasonably competent surgeon can expose the intracranial carotid artery proximal to the takeoff of the ophthalmic artery. While this exposure is invaluable for managing neoplastic diseases of the area, it is not as critical for obtaining proximal control of the aneurysms in question. The reason underlying this seeming paradox is simple: once the ICA proximal to the ophthalmic origin is exposed and occluded with a temporary clip, a surgeon does not have sufficient working room to either expose and manipulate the adjacent aneurysm or to apply permanent clips in a fashion certain to span the aneurysm neck, as demonstrated in Fig. 4.2. Fortunately, cervical exposure of the ICA is beneficial/advantageous in several ways. It provides excellent (and early) proximal control, does not hinder aneurysm dissection or clipping, permits retrograde suction-decompression of the aneurysm, and also facilitates intraoperative angiography. This initial exposure, obtained prior to performing the craniotomy, is recommended in all ruptured and giant lesions; in contrast, when dealing with smaller aneurysms, the neck is always prepped and draped, but the craniotomy is performed first. The aneurysm should be exposed intradurally before a decision regarding the advisability of cervical carotid exposure is made. Fig. 4.1 Aneurysms of the proximal carotid artery. Fig. 4.2 Demonstration of limited room for proximal temporary clip application. Aneurysms of the proximal intracranial ICA are easily exposed via a routine pterional craniotomy, which extends anteriorly to the midpupillary line and posteriorly exposes the sylvian fissure. Unless the surgeon elects to remove the anterior clinoid process extradurally, a normal resection of the sphenoid wing will suffice. Most aneurysms of regular or large size can be operated on without opening the sylvian fissure or mobilizing the temporal lobe; in fact, wide opening of the sylvian fissure makes the main trunk and branches of the middle cerebral artery (MCA) vulnerable to subsequent inadvertent injury by the shaft of the microdrill. This action/risk should be avoided when possible. For the same reason, it is often wise to place a self-retaining retractor blade gently over the tip of the temporal lobe and its associated draining veins, especially in the case of a right-handed surgeon operating through a right-sided exposure (Fig. 4.3). Fig. 4.3 Application of temporal lobe retractor. The initial opening of the basal cisterns should begin with the carotid cistern, rather than the prechiasmatic cistern, for obvious reasons. The surgeon should also recall that large proximal ICA aneurysms tend to displace the supraclinoid carotid posteriorly, sometimes by a surprising amount. A single self-retractor blade placed on the posterior aspect of the orbital cortex adjacent to the sylvian fissure will provide excellent exposure of the carotid cistern. Once that cistern has been opened and cerebrospinal fluid removed, almost all ICA-ophthalmic and posterior carotid wall aneurysms will be visible to some degree (Fig. 4.4). The temptation to proceed directly to aneurysmal dissection is difficult to resist; nonetheless, a wiser course is to complete the dissection of the ICA distal to the lesion, then to prepare the artery for temporary occlusion, if necessary, proximal to the origin of the PCOMM. This exposure will also delineate the distal aspect of the necks of ophthalmic and posterior carotid wall lesions. The surgeon’s attention now turns to exposure of the proximal portion of the aneurysm, which almost invariably means removal of a portion of the skull base adjacent to the ICA and optic nerve. Fig. 4.4 Visualization of proximal carotid wall aneurysms. The focus of skull base resection in these cases should be exposure of the aneurysm itself to facilitate dissection of the neck and permanent clip application. For ophthalmic origin aneurysms, this generally means unroofing of the optic canal, aggressive resection of the optic strut, and minimal removal of the anterior clinoid process (Figs. 4.5 and 4.6). More of the clinoid process must be resected for superior hypophyseal aneurysms, but often unroofing of the optic canal is not necessary (Fig. 4.7). ICA-paraclinoidal lesions almost always require an aggressive removal of the anterior clinoid process, but the optic strut and orbital roof can remain intact (Fig. 4.8). The question of exactly how much bone should be removed is frequently posed. There is no one absolute answer. However, the surgeon can begin by turning a semilunar dural flap hinged medially. This exposes the roof of the canal, the underlying strut, and the anterior two thirds of the clinoid process, which will provide sufficient exposure for the surgeon to cope with virtually any eventuality (Fig. 4.9). Fig. 4.5 Unroofing of optic canal. Fig. 4.6 Removal of optic strut. Fig. 4.7 Removal of anterior clinoid process. Fig. 4.8 Aggressive removal of anterior clinoid process.

Aneurysms of the Proximal Internal Carotid Artery

General/Anatomy

Proximal Control

Procedure: Craniotomy and Initial Approach

Aneurysm Exposure

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree