Ankylosing Spondylitis

Cheerag D. Upadhyaya

Rick C. Sasso

Praveen V. Mummaneni

Ankylosing spondylitis is a seronegative, systemic, inflammatory rheumatic spondyloarthropathy mainly affecting the spine and sacroiliac joints. Ankylosing spondylitis is the third most common arthritic condition in the United States and involves an HLA-B27 genetic predisposition in the majority of cases (1,2). The disease is characterized by a diffuse inflammatory reaction resulting in ossification of spinal ligaments, joints, and intervertebral disks. Over time, the once dynamic and flexible spinal column becomes a rigid, osteoporotic, and deformed lever arm, increasingly susceptible to deformity due to fractures from minor forces (3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8).

Cervical spine fractures in patients with ankylosing spondylitis typically occur at the level of the ossified intervertebral disk (9, 10, 11 and 12). Such injuries often result in neurologic deficits that necessitate early and aggressive surgical management with posterior and/or anterior fixation techniques to enable neural decompression, spinal stability, and optimal functionality (3,13).

SURGICAL INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

Only 0.5% of ankylosing spondylitis patients undergo cervical surgery, and, of those, one-third require surgery for deformity correction and two-thirds require surgery for spine fractures (14). Fractures in patients with ankylosing spondylitis are particularly unstable as they typically involve both the ventral and dorsal elements. These fractures often require surgical stabilization (4). For those who do not undergo surgical stabilization, as many as 60% go on to develop progressive neurologic injury secondary to delayed dislocation at the original fracture site (7,15,16). The surgical indications in ankylosing spondylitis patients include cervical fractures, cervical deformity, and cervical stenosis with myelopathy or radiculopathy (Table 63.1).

Relative contraindications to surgery in this patient population include cardiovascular disease, pulmonary disease, bleeding diathesis, and severe osteoporosis (17).

PREOPERATIVE ASSESSMENT

Patients with ankylosing spondylitis often have medical comorbidities. A careful preoperative history and physical examination helps to identify these issues. These patients often have a thoracic kyphotic deformity, which predisposes them to reduced pulmonary function. Furthermore, their use of medications such as methotrexate can interfere with wound healing. Furthermore, patients with severe cervical deformities (chin-on-chest deformity) may have poor nutrition secondary to swallowing problems. A neurologic examination should focus on signs of myelopathy.

Radiographic analysis includes full 36-inch standing scoliosis x-rays. We prefer to define the cervical and thoracic bony anatomy with CT scans with coronal and sagittal reconstructions, and MRI scans to evaluate for neural compression and intraspinal hematomas (in the setting of acute fractures). Furthermore, we typically prefer to obtain a CT of the head to assess for adequate skull thickness in cases in which we will be applying cranial pins for traction.

ALGORITHM FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF CERVICAL ANKYLOSING SPONDYLITIS

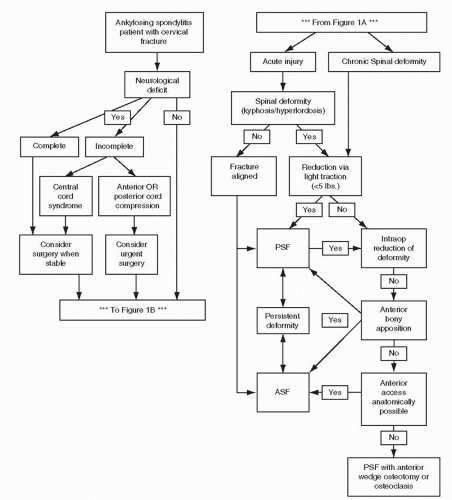

Figure 63.1 depicts a proposed algorithm for the management of patients with ankylosing spondylitis and cervical deformity (with or without neurologic deficits) (18). Surgical decompression should probably be performed urgently in patients with incomplete spinal cord injuries, whereas those with complete or central cord injuries may be treated in a delayed fashion. As previously stated, ankylosing spondylitis patients often have medical comorbidities that require optimization prior to surgery. However, if they have acute fractures, these patients typically have overt instability and are susceptible to neurologic injury with even mild movements. These two issues—medical comorbidities and acute instability—must be considered when timing surgical intervention. In addition, two issues that

should be addressed when considering surgery for cervical fractures in ankylosing spondylitis patients are their poor bone quality and the long lever arms affecting the injured segment secondary to the ankylosed spine (13). To combat these drawbacks, two to three levels of fixation should be considered above and below the fracture.

should be addressed when considering surgery for cervical fractures in ankylosing spondylitis patients are their poor bone quality and the long lever arms affecting the injured segment secondary to the ankylosed spine (13). To combat these drawbacks, two to three levels of fixation should be considered above and below the fracture.

TABLE 63.1 Indications and Contraindications | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Acute injuries without spinal deformity may be managed with either a ventral or dorsal spinal fusion, depending on the level of injury. Patients who present

with acute spinal deformity, as well as those with delayed, nonhealed injuries, may be placed in modest cervical traction (<5 pounds) to attempt fracture reduction and spinal realignment. If realignment with ventral bone apposition is accomplished, dorsal spinal fusion and fixation can be performed.

with acute spinal deformity, as well as those with delayed, nonhealed injuries, may be placed in modest cervical traction (<5 pounds) to attempt fracture reduction and spinal realignment. If realignment with ventral bone apposition is accomplished, dorsal spinal fusion and fixation can be performed.

Figure 63.1. Flowchart for the management of ankylosing spondylitis and cervical spine fractures with neurologic injury (A) and/or spinal deformity (B) (18). |

In more severe kyphosis cases (such as chin-on-chest), ventral anatomic access is limited. In such cases, prolonged cervical traction (several days in an intensive care unit with low traction weight) may help to pull the chin off the chest and allow for a ventral surgical approach. It is imperative to avoid using heavy weights for traction (over 10 pounds). This may cause a sudden distraction fracture of the spine. Traction is typically successful if the pretreatment CT scan shows a lack of ventral bony fusion or very weak bridging bone across the ventral aspect of a focal kyphotic fracture segment.

In cases with complete ventral fusion in a kyphotic deformity, the authors turn instead to the use of spinal osteotomies. If ventral access is anatomically possible, ventral wedge release via osteotomy can be performed, followed by dorsal spinal fusion to restore craniocervical alignment (17). If ventral access is anatomically not possible, then we typically turn to a dorsal-based osteotomy and fusion (with or without a subsequent ventral approach). The two most typically used dorsal osteotomies are multilevel facet osteotomies and pedicle subtraction osteotomy (PSO). Multilevel dorsal facet osteotomies are most useful for multilevel, sweeping kyphosis. A small degree of correction from facet resections across multiple levels is often satisfactory to realign such kyphosis. Dorsally based PSO, on the other hand, is typically used if there is a focal kyphotic fracture at the cervicothoracic junction.

Cervical PSO procedures are rarely reported in the literature. Simmons initially described the cervical dorsal wedge osteotomy technique, performed in the awake sitting position without dorsal instrumentation (19,20). McMaster (21) reported on his experience in performing 15 C7-T1 wedge osteotomies in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. He obtained a mean kyphosis correction of 54 degrees with restoration of lordosis in all cases but at the expense of a relatively high complication rate— including two patients with C8 nerve root palsies, four with progressive subluxations, two with pseudoarthroses, and one patient with quadriparesis. Mehdian et al. (8) were among the first to expand on Simmons’ technique, with the incorporation of dorsal instrumentation to avoid sudden spinal subluxation during the correction maneuver and to avoid the use of postoperative halo immobilization. Several authors of more recent studies have reported similar findings with unique variations in technique to minimize complications and maximize deformity correction. These include the use of transcranial electrical stimulated motor evoked potential monitoring and controlled intraoperative extension osteotomy on a Jackson table (22,23) The authors utilize this technique if the focal kyphotic fractured segment is at C6-T1 (below the vertebral artery’s entry into the foramen transversarium). If a PSO is performed above C6, a theoretical risk of vertebral artery kinking in the foramen transversarium during reduction of the osteotomy exists. In such cases, the authors prefer to utilize a combined two- or three-stage osteotomy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree