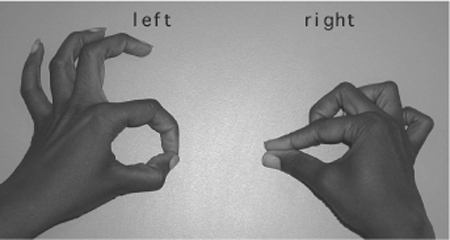

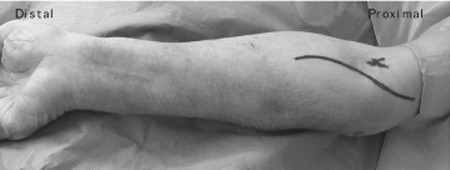

20 Anterior Interosseous Nerve Syndrome/Compression A 52-year-old female presented with a year-long history of progressive pain in her right upper extremity. Over the previous several months she had also developed weakness in the hand. She complained of pain throughout her right supraclavicular area, shoulder, and forearm. She was experiencing difficulty picking things up with her right hand. There was no history of trauma or other injury to her arm or cervical area; however, her employment involved the packing of boxes, which required a repetitive pronation/ supination type of movement. The patient had undergone 6 weeks of physical therapy with no relief of pain or improvement in motor function. On examination there was pain to palpation over the volar surface of the forearm. She exhibited thenar wasting as well as weakness of Medical Research Center (MRC) grade 4 in the flexor digitorum profundus I and II, and flexor pollicis longus muscles on motor testing. She exhibited the inability to form a pinch with the first digit and the thumb (Fig. 20–1). The muscles of her main median nerve distribution, as well as ulnar and radial distribution, were intact to motor testing. Sensory examination was intact to pinprick and light touch modalities throughout all dermatomes. Reflexes were 2/4 and symmetric throughout. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the cervical spine was negative for any disk disease, foraminal stenosis, or intrinsic cord disease. Electromyographic (EMG) and nerve conduction studies revealed decreased recruitment in the pronator quadratus, flexor digitorum profundus, and flexor pollicis longus. Positive sharp waves and fibrillations, reflecting muscle denervation, were seen in the pronator quadratus. Figure 20–1 Patient exhibiting typical inability to perform pinch on affected right hand. Anterior interosseous syndrome The median nerve, with contributions from nerve roots C6, C7, C8, and T1, after traveling down the medial surface of the arm, enters the cubital fossa posterior to the lacertus fibrosis (bicipital aponeurosis). This fibrous band of tissue is a tendinous insertion of the biceps brachii muscle. The nerve lies medial to the brachial artery and anterior to the brachialis muscle. The nerve most commonly lies in the proximal forearm between the superficial and deep headsof the pronator teres and gives off branches as it passes through this muscle. However, many variations in its relationship to the heads of the pronator muscle have been described. Once past the pronator teres, the nerve passes deep to the arch of the flexor digitorum superficialis. The anterior interosseous nerve, with contributions primarily from C7 and C8, branches from the median nerve just proximal to the arch of the flexor digitorum superfi cialis and 5 to 8 cm distal to the medial epicondyle. As it passes between the flexor digitorum profundus and superficialis it comes to lie on the anterior interosseous membrane. The nerve then goes on to innervate the flexor digitorum profundus I and II and the flexor pollicis longus and will terminate in the pronator quadratus muscle. It provides two to six branches to each of these muscles. Although the anterior interosseous nerve gives sensory innervation to the distal radioulnar, radiocarpal, intercarpal, and carpometacarpal joints, it gives no cutaneous innervation. In ˜;15% of limbs, a Martin-Gruber anastomosis may occur. In this anatomical variant the median nerve carries ulnar fibers that then, via the anterior interosseous nerve, anastomose to the ulnar nerve. The ulnar nerve then carries these fibers on to ulnar innervated structures in the hand. When this anatomical variant is present an anterior interosseous syndrome may also exhibit weakness in the intrinsic muscles of the hand. In the complete anterior interosseous nerve syndrome all of the muscles innervated by the nerve are involved, but variations and incomplete syndromes are common. There is commonly a history of progressive pain in the arm and forearm that is then followed by muscle weakness. A history of repetitive-type movements, either work related or recreational, is common, and these movements will often exacerbate the pain. Once the muscle weakness begins, the pain often subsides and may even disappear completely. At this point the patient often complains of difficulty picking up small objects, closing buttons, or writing. Incomplete flexion of the interphalangeal (IP) joint of the thumb, from flexor pollicis longus weakness, and the distal interphalangeal (DIP) of the index and second finger, from flexor digitorum profundus weakness, are seen on examination. This results in an inability to perform a pinch-type maneuver with the affected hand (Fig. 20–1). Instead of the tip of the thumb and first finger being brought together the patient is only able to appose the pads of these fingers. Weakness of forearm pronation will also frequently be present but is difficult to demonstrate because the pronator teres is still functional and it is dif-ficult to isolate the action of the pronator quadratus. No sensory deficit will be noted. The clinical presentation of anterior interosseous nerve syndrome may be variable. Atypical or incomplete syndromes are not uncommon; therefore, many etiologies may mimic this condition. Cervical spine disease from spondylitic, neoplastic, or diskogenic causes should be ruled out with appropriate MRI studies. Brachial plexopathy, neuralgic amyotrophy (pain in the shoulder girdle and weakness of the shoulder girdle musculature), attritional rupture of the flexor pollicis longus or flexor digitorum profundus tendons to the index finger (as seen in rheumatoid patients, Kienböck disease, and nonunion of scaphoid fractures) should also be ruled out. Pseudoanterior interosseous syndrome can result from a partial lesion of the median nerve 2.0 to 2.5 cm proximal to the branching off of the anterior interosseous. At this anatomical location the anterior interosseous exists as a distinct bundle within the median nerve, and any lesion that is pressing the posterior portion of the nerve may result in a pseudoante-rior interosseous syndrome. Careful clinical examination and EMG studies with inching technique can distinguish these various syndromes. The inability to perform a pinch maneuver is almost pathognomonic for this syndrome. If median nerve sensory loss is present, consider median nerve pathology elsewhere or in the wrist (carpal tunnel). EMG and nerve conduction studies are essential to confirm a working diagnosis of anterior interosseous syndrome and rule out other etiologies in the differential diagnosis. Needle studies will often show fibrillations, positive sharp waves, and reduced interference patterns in the affected muscles, particularly the flexor pollicis longus and the pronator quadratus. The flexor digitorum profundus may be difficult to locate due to technical issues and therefore is frequently not well demonstrated on EMG studies There are many causes of this syndrome, including trauma (fractures, stab wounds, elbow dislocations), systemic problems (polyarteritis nodosa, cytomegalovirus), vascular maladies (ulnar vessel thrombosis, aberrant radial artery, Volkmann ischemia), and other rare etiologies. Up to one third of all cases of anterior interosseous syndrome occur spontaneously, and this is the single largest cause encountered. In these cases entrapment or compression has most often been identified as the etiology at operative exploration. Because there are no prospective, controlled studies regarding conservative treatment, only recommendations can be offered. Generally, if the syndrome has persisted for more than 3 weeks, EMG studies should be obtained and a period of conservative therapy instituted. This should include oral anti-infl ammatory medications and refraining from any repetitive supination/pronation activity that exacerbates the condition. Steroid injections remain controversial. If the symptoms persist for more than 8 to 12 weeks and no improvement is noted either clinically or electrodiagnostically, surgical intervention is warranted. There are several sites along the course of the nerve that may be the source of the compression and they should be identified and released to insure proper decompression and recovery of the nerve.

Case Presentation

Case Presentation

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Anatomy

Anatomy

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Diagnostic Tests

Diagnostic Tests

Management Options

Management Options

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree