Anterior Multilevel Decompression: Discectomies versus Corpectomy

Ben B. Pradhan

The indications and techniques for ventral cervical spine surgery are discussed in separate dedicated chapters in this textbook. The most commonly performed ventral cervical spine surgeries are anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) and anterior cervical corpectomy and fusion (ACCF). While there are specific indications for performing an ACDF (single-level disk pathology) and an ACCF (retrovertebral pathology ventral to the spinal cord), there are instances where either of these two techniques can be used. Multilevel disk pathology without retrovertebral extension is such an instance. If retrovertebral pathology is present, partial or complete corpectomies may be necessary. In this chapter, the pros and cons of performing multilevel ACDF versus ACCF for disk pathology are discussed. There are proponents for both techniques, as well as detractors.

There are those who believe in changing and sacrificing as little of the body’s natural structures (being anatomy-preserving) as possible and who argue that removing the entire vertebral body is unnecessary and may be detrimental. Others believe that the fewer the moving parts, the better and prefer a single strut graft as opposed to multiple interbody grafts. There are also those who believe that one technique is easier to perform than the other and takes less time. Obviously, if a particular technique is easier and faster for a surgeon than another, then that is the better technique in his/her own hands.

ACDF IS BETTER

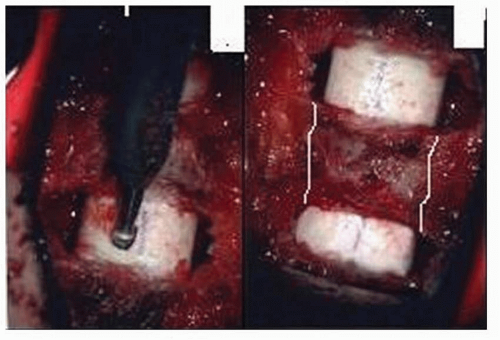

In both ACDF and ACCF techniques, native structures are removed and reconstructed with grafts. One truism in life is that we can rarely recreate nature’s work. So preserving as much of the human anatomy as possible is naturally advantageous. Also, the more we do in the human body, the more the undesirable collateral effects (such as bleeding, scarring, weakening, alteration of mechanics). If the nerve compression is only at the disk space, then proponents of ACDF state that it is better to just remove the disks and reconstruct the disk spaces. This approach leaves the nonpathologic tissues alone because invariably they cannot be reconstructed the way nature intended them to be, and this potentially may have unintended consequences on adjacent structures. ACDF may be easier than ACCF because extensive bone removal is not necessary, and there is less bleeding (from bony surfaces). The bone work is limited to foraminotomies and preparation of the end plates, so bony bleeding should be less than during a corpectomy. However, this last argument goes both ways since ACDF requires more time spent working in confined and often collapsed disk spaces (Fig. 136.1).

There is also the argument that multilevel ACDF is a more stable construct than ACCF. An ACCF has only the two ends of a long strut graft where loading transpires from the upper vertebra of the cervical spine to lower vertebrae. So the ends of the graft are subject to more destabilizing forces (translational and subsidence) because of the long lever arm of the strut graft or cage and because it spans multiple motion segments. This is as opposed to individual intervertebral grafts, which must resist only single-motion segment loading. Moreover, with anterior cervical plates and screws, each vertebra can be segmentally instrumented to create a much more stable construct (1, 2 and 3). Segmental instrumentation is not possible after ACCF.

Because ACCF consists of a single long graft, there may be a tendency to place it under either too much or too little tension. When the tension during graft placement is too high, subsidence of the graft into the vertebrae can occur. When the tension is too low, dislodgment can occur. In the literature, the prevalence of graft slippage after ACDF surgery is 1% to 2%, while that of a strut graft after ACCF is 6% to 29%, with the inferior end of the graft dislodging most often (4,5). The addition of plate and screw instrumentation reduces this rate, but more so in multilevel ACDF because each segment (vertebrae) can be instrumented (Fig. 136.2) unlike in ACCF where only the end vertebrae can be instrumented (Fig. 136.3).

Sagittal alignment of the cervical spine (lordosis) is important to restore and maintain because it has consequences on the health of the muscles that stabilize the spine and the remaining disks and also prevents any draping of the spinal cord on the dorsal surfaces of the vertebrae in a kyphotic spine (6). The fact that the cervical spine has multiple disks is advantageous because each disk

contributes to the cervical lordosis incrementally, creating a smooth gradual curve. It follows then that if multilevel disk surgery is performed, reconstructing each disk segment separately with grafts of the appropriate height or lordosis will impart a more natural and stable sagittal alignment compared to a long straight strut graft. An analogy may be drawn to segmental spinal instrumentation versus a long Harrington rod instrumentation in the lumbar spine. Though proponents of ACCF will state that cervical lordosis can be reliably restored and maintained, what they cannot promise is that each segment is distracted equally and will thus contribute incrementally to the overall lordosis

as it naturally should. With a single graft spanning multiple disk spaces, the most flexible or unstable segments will contribute most to the lordosis, which may place undue stress and stretch at that segment. Therefore, indirect decompression by distraction may not occur equally in all the segments. This can be better controlled during ACDF by the proper choice of graft size at each segment. This concept is illustrated in Figure 136.4 with the spine represented schematically by a spring.

contributes to the cervical lordosis incrementally, creating a smooth gradual curve. It follows then that if multilevel disk surgery is performed, reconstructing each disk segment separately with grafts of the appropriate height or lordosis will impart a more natural and stable sagittal alignment compared to a long straight strut graft. An analogy may be drawn to segmental spinal instrumentation versus a long Harrington rod instrumentation in the lumbar spine. Though proponents of ACCF will state that cervical lordosis can be reliably restored and maintained, what they cannot promise is that each segment is distracted equally and will thus contribute incrementally to the overall lordosis

as it naturally should. With a single graft spanning multiple disk spaces, the most flexible or unstable segments will contribute most to the lordosis, which may place undue stress and stretch at that segment. Therefore, indirect decompression by distraction may not occur equally in all the segments. This can be better controlled during ACDF by the proper choice of graft size at each segment. This concept is illustrated in Figure 136.4 with the spine represented schematically by a spring.

Figure 136.1. Two-level ACDF surgery. Note that aside from the diseased disks and medial aspect of the uncovertebral joints, very little of the vertebra itself is removed. The white lines in the picture on the right indicates what bone would be removed as well during a corpectomy surgery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|