19 Anterior Skull Base Surgery • The most common primary tumors in the anterior skull base (ASB) are meningiomas (~ 20% of intracranial tumors, ~ 40% when considered together with the sphenoid wing meningiomas).1 Tuberculum sellae meningiomas are central skull base tumors, but they are discussed here in the differential diagnosis of olfactory groove and planum sphenoidale meningiomas. • Among the malignant tumors of the sinonasal tract, esthesioneuroblastoma is the most common. In children, sarcoma is the most common malignant tumor of the ASB. • Carcinoma of the ethmoid sinuses/nasal cavity with skull base involvement. • Bony metastases (especially breast, lung, prostate, and myeloma). • Very rare anterior cranial fossa schwannoma (most likely from the ethmoidal nerves or meningeal branches of the trigeminal nerve2,3). • Other rarer conditions, such as sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, brown tumors, and mucoceles, can affect the region. Malignant tumors have traditionally been treated with en-bloc resection of the ASB whenever possible. A malignant tumor that transgresses the dura and brain parenchyma has a poorer prognosis (see Chapter 23). • Olfactory groove meningiomas account for 9 to 18% of all meningiomas.4,5 • They originate in cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone and sphenoethmoidal suture.6,7 • They may involve any area from the crista galli to the planum sphenoidale, extending back into the pituitary fossa and laterally above the orbits. • Because of frontal lobe compression, they often cause behavioral or mental status changes, which are subtle in the beginning and may go unrecognized for years. Headache and anosmia are other common features. In posteriorly placed lesions such as those arising from or extending posterior to the planum or those extending posterior to the optic system, visual disturbances may be present. Historically, Foster Kennedy syndrome is considered a sign of a frontal fossa meningioma, but generally occurs only in the largest tumors (see page 183). Olfactory groove meningiomas typically depress the optic chiasm as they extend backward, whereas tuberculum sellae meningiomas elevate it.8 Olfactory groove meningiomas have the following attributes: • Possible bone erosion, and ~ 20% of cases include ethmoid sinus invasion.5,9,10 • Possible displacement/involvement/encasement of the olfactory nerves. By definition, the olfactory groove meningioma starts at the level of the olfactory nerves. • Blood to these tumors is supplied by the ethmoidal arteries and sphenoidal branches of the middle meningeal artery. • Tuberculum sellae meningiomas account for 5 to 10% of all intracranial meningiomas. • They originate in the region of the chiasmatic sulcus and tuberculum sellae. • In comparison with the other ASB meningiomas, lesions arising from the tuberculum give rise to visual disturbances earlier, typically causing bitemporal (or only superolateral) hemianopsia.11 • Tumors that start parasagittally or extend into one optic canal more than the other may present with asymmetric visual field loss, typically one-and-a-half syndrome, a relative afferent pupillary defect, and unilateral optic atrophy (see Chapter 10). • The vascular supply comes from the posterior ethmoidal arteries and the meningeal vessels from the internal carotid artery (ICA). Preoperative embolization is often not feasible for these tumors.12 • Visual losses present sooner in patients with prefixed chiasms (i.e., shorter optic nerves) (see Fig. 3.2b, page 75). Signs and symptoms include headache, olfactory disturbances/anosmia, visual field deficits (inferior or bitemporal visual field defects, depending on the size of the tumor and involvement of the optic chiasm, especially for tuberculum sellae [TS] meningiomas), frontal lobe syndrome with mental deterioration, and short-term memory loss. Patients may also present with behavioral, personality, or psychiatric symptoms and may also appear depressed and apathetic. In older patients, these symptoms may be mistaken for dementia. Patients may also present with seizures, although this is rare. Fig. 19.1 Tuberculum sellae meningioma. AcomA, anterior communicating artery; OC, optic canal; ON, optic nerve. • The more anteriorly placed the lesion, the more likely the patient will present with headache, anosmia, and behavioral change. The more posteriorly placed the lesion, the more likely the patient will present with visual complaints. • Pain and nasal symptoms of obstruction and epistaxis are more common in lesions arising in the sinuses, which, as a group, are much more likely to be malignant. Typical radiological work for meningiomas entails computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). CT is essential for defining hyperostosis and bone erosion. MRI is essential for defining localization and involvement of the optic chiasm and frontal lobe edema (T2 sequences). MRI with fat suppression is useful to identify tumor extension into the optic canal. Computed tomography angiography (CTA) or, rarely, angiogram may be required to define the relationships of the tumors with anterior cerebral arteries (see Chapter 5, page 114). The workup includes the following: • Neuro-ophthalmologic testing (visual acuity, visual fields, color vision, optical coherence tomography [OCT]) (see Chapter 10) • Endocrinologic testing for pituitary gland/hypothalamus hormonal functionality in tumors compressing the pituitary gland/stalk or hypothalamus (see Chapter 9) • Neuropsychological testing (e.g., Montreal Cognitive Assessment, Folstein Mini–Mental State Examination, or other tests of cognitive abilities); particularly helpful as baselines for the long-term follow-up of patients Asymptomatic small meningiomas should be followed over time. Radiosurgery is an option for patients in whom surgery is contraindicated, although surgery remains the gold standard of treatment, especially for symptomatic patients who have signs of rapid visual deterioration. Surgical approaches are shown in Fig. 19.2. See also Chapter 14. These approaches provide broad exposure of the anatomic region and tumor, with direct access to the anterior skull base if required. • The pericranial flap can be easily used for reconstruction of the anterior fossa, if necessary (see Fig. 14.3, page 342). • Depending on tumor size and extension, opening the frontal sinuses becomes inevitable in some cases. Brain retraction should be avoided. Judicious use of lumbar drainage and performing the craniotomy as basal as possible are important caveats. Orbitozygomatic (OZ) osteotomy or simply an orbitocranial (OC) osteotomy in addition to the frontal craniotomy offers a more basal approach to the tumor, reduces the necessity to retract the frontal lobes, and particularly facilitates skull base reconstruction with pericranial flaps. • Extradural dissection with extensive devascularization of the tumor is particularly helpful. However, the anterior cerebral arteries should be left covered by arachnoid and not disturbed. The optic nerves and chiasm are usually visualized at later stages of dissection of the anteriorly placed tumors and should not be manipulated. • Midline olfactory groove tumors, most of which are of considerable size, often require ligation and division of the superior sagittal sinus. • For surgical approaches, see Fig. 19.2. For surgical steps, see Chapter 14, page 335. • Orbital osteotomy may be used to enhance the exposure, reduce brain retraction, and facilitate repair. This approach has been described for resection of olfactory groove meningiomas13,14 and TS meningiomas,15,16 but it is limited by narrow corridors in reaching the tumor. The corridors can be enlarged only by the mediolateral displacement/retraction of the frontal lobes, a process that entails the risk of injury to the bridging veins. Surgical Anatomy Pearl Do not retract both frontal lobes. Different frontolateral approaches can be used for asymmetric ASB tumors extending to one side. The side of the approach is generally the side of maximal extension of the tumor or of the visual field deficit. However, in TS meningiomas with visual impairment, a contralateral approach has been also suggested for providing potentially better visual outcomes.17 Surgical Anatomy Pearl If the ICA is encased, perform the exposure on the side of the encased ICA itself. In comparison with the bifrontal approach, the frontotemporal craniotomy spares the superior sagittal sinus and the cortical veins, and generally the frontal sinus does not have to be opened. This approach enables early dissection of the neurovascular complex.18 The smaller unilateral pterional craniotomy can also be useful, but requires drilling of the anterior fossa floor and less flexibility to extend the exposure subfrontally for larger and contralateral tumors. However, it has been shown to be safe even when combined with a transsylvian exposure.19,20 This approach, with or without an orbital osteotomy, provides excellent basal exposure. See Fig. 14.12, page 362. Olfactory groove meningiomas21 and TS meningiomas22 can be approached by means of this approach, with results comparable to those of the other more time-consuming approaches in terms of morbidity and mortality. However, the narrower approach may limit the ability to deal with the ICA. This approach has been suggested for meningiomas of the anterior and central skull base,23,24 although there is a limitation in the exposure of the tumor due to the restriction on available space intraoperatively. The visualization of the contralateral side of the tumor and anatomic structures is also more difficult. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) drainage (by means of lumbar drainage or cisternal openings) is helpful in all approaches for minimizing brain retraction. However, in the event of a dissection of the subarachnoid space, the lumbar drain may make the arachnoid dissection more difficult because it may empty the cisterns of CSF. • The risk of CSF leakage has to be evaluated with all approaches, and the surgeon must be prepared to repair any such leak. • Frontal sinuses may often be avoided by means of these approaches. However, in cases where the frontal sinuses are transgressed, they should be repaired. If the opening is small (< 1 cm) and the mucosa intact, simple bone wax may suffice. For larger breaches of the sinus, the mucosa should be exenterated completely and the inner surface of the sinuses lightly drilled with a diamond bit. The frontal sinus ostium can be plugged with Gelfoam or fat, and then the sinus covered with a vascularized, pedicled pericranial flap harvested from the frontal scalp. Laying down the pedicled flap across the floor of an orbital cranial osteotomy avoids strangulating the flap that travels across a base of frontal bone left in place after a craniotomy. If orbital bony protuberances narrow the surgical corridor, drill them down. Olfactory nerve preservation seems to be less successful in surgeries using a supraorbital approach than in more extended craniotomies. Selected cases, such as olfactory groove or TS meningiomas (i.e., small midline lesions with no major vessel encasement, limited or no parasellar extension, or tumor extension into the sphenoid sinus) can be treated by means of an extended endoscopic transsphenoidal approach.25–27 See also Chapter 16. • The resection via a transsphenoidal route facilitates decompression of critical structures, such as the optic nerves and chiasm from below, rather than working on these structures from above and needing to work around them to get to the tumor. The approach also requires resection of involved bone and dura, but whether recurrences will be fewer as a result of using this approach has yet to be determined and requires an analysis of long-term follow-up data. • It is a demanding technique, and surgeons should have considerable training and experience before attempting this approach. Close attention to whether the tumor extends or encases the optic nerve and major vessels requires high-resolution imaging. The combination of the frontal craniotomy with a transnasal endoscopic approach can be used for large meningiomas or malignant tumors involving large areas of the brain cavity and the nasal cavity or paranasal sinuses, or for those where an en-bloc resection is considered essential.28–30 The endoscopic endonasal approach enables the resection of the nasal/paranasal component of the tumors. On the other hand, the subfrontal approach enables the resection of the intracranial components, removal of the involved dura, and drilling of the cribriform plate. The technique is mostly used for the surgical resection of malignant sinonasal lesions. • Some contraindications have been described for the use of this approach, such as lacrimal sac or orbital involvement, nasal pyramid or bony walls of the maxillary sinus involvement, and extension to the pterygopalatine or infratemporal fossa.31 • The endonasal endoscopic phase involves various combinations of the endoscopic approaches (e.g., transsphenoidal/transplanum/transcribriform approaches): lamina papyracea dissection, and further approaches such as medial maxillectomy, nasolacrimal duct exposure, removal below the lacrimal sac, and periorbital resection depending on tumor localization.32 • The transcranial phase involves a bifrontal craniotomy with a coronal incision for tailoring of a pedicled pericranial flap, which will be used in the reconstruction phase. The flap should be made as long as physically possible. Frontal lobe retraction can be avoided by using a low craniotomy with or without an orbital cranial osteotomy and with early CSF drainage. The anatomy of the lesion will determine the extent of bone resection. Reciprocating saws or fine drills can help facilitate en-bloc resection of bones.32 Resection of dura and involved brain can be performed in subsequent steps based on preoperative imaging (look for enhancement and thickening of the meninges and edema or enhancement of the brain) and intraoperative “quick section” pathology. • Working from different angles, head and neck surgeons and neurosurgeons can simultaneously visualize the margins of the resection. • For cases with resection of dura, the dura can be reconstructed with a fascia lata free graft sutured in place. The pedicled pericranial flap is sutured down to the deepest aspects of the resection, just beyond the margins of the dural repair. Layered free fat grafts and fibrin glue may also be useful to support the repair. For defects adequately repaired by this technique via craniotomy, bone reconstruction is not necessary. The endonasal cavity can be reconstructed with a pedicled nasoseptal flap to aid in mucosal healing (see “Endoscopic Repair of Skull Base Defects,” page 431). • The overall complication rate depends on the patient population and the size of the lesions being treated. In one series, the overall complication rate was 16%,30 and associated complications included CSF leakage (generally managed by lumbar drainage), frontal bone osteomyelitis, epistaxis, supraorbital anesthesia, and visual disorders. For any meningioma surgery, whether done from above or below the skull base, devascularization of the tumor should be performed prior to tumor resection. All hyperostotic bone should be removed. • Imaging with CT or MRI should be carefully studied in every case to assess the transbasal extension. The goal of every surgical procedure should be gross total resection. Reconstruction should be an essential part of the planning phase in every case as well. • Olfactory nerves should be anatomically preserved if possible. Dissect them from the tumor, open the olfactory cisterns, and avoid coagulation in this region. During resection of planum sphenoidale and olfactory groove meningiomas, both olfactory nerves are dissected and, if necessary, one is divided while leaving the other intact whenever possible. • The anterior cerebral arteries should be left untouched behind the arachnoid membrane. If this is not possible, they must be dissected carefully from the posterior pole of the tumor from below in order to preserve all the perforating arteries and the recurrent arteries of Heubner. • In tumors involving the optic nerves, extradural optic nerve decompression may be required. Optic canal involvement (above all in TS meningiomas) requires optic nerve decompression33,34 by means of the unroofing of the optic canal, extradural anterior clinoidectomy with falciform ligament and optic nerve sheath opening, and endoscopic transnasal procedures. • No coagulation is recommended in the vicinity of the optic nerves and chiasm. Preserve the perforators close to the chiasm; apply haemostatic material in case of bleeding rather than performing hemostasis with the bipolar forceps. • Avoid frontal lobe retraction, considering that the frontal lobe may already be quite edematous, and retractors can make it worse. • The tumor generally pushes the pituitary stalk backward, and it is usually possible to preserve the arachnoid membrane, the stalk, the basilar artery, and its branches.1 The possibility of total resection depends on the patient and tumor characteristics such as tumor extension, invasiveness, and encasement of arteries of the anterior cerebral complex.35 For confined meningiomas, gross total resection is often possible, whereas malignant tumors with brain invasion are rarely completed resected. Frontal basal syndromes can be prevented by avoiding brain retraction and preservation of all arteries and veins. • In TS meningioma, when comparing different approaches, the frontolateral approaches have been shown to provide the best visual outcome in comparison with bifrontal approaches.36 • In olfactory groove meningiomas, olfaction may be preserved in the contra-lateral side of tumors less than 3 cm in diameter, whereas its preservation ipsilaterally to the tumor is extremely difficult.37 • Table 19.1 summarizes outcome and complications of surgery for olfactory groove meningiomas8,23,38,39 and Table 19.2 for tuberculum sellae meningiomas.26,40–42

Tumors of the Anterior Skull Base

Tumors of the Anterior Skull Base

Olfactory Groove Meningiomas

Olfactory Groove Meningiomas

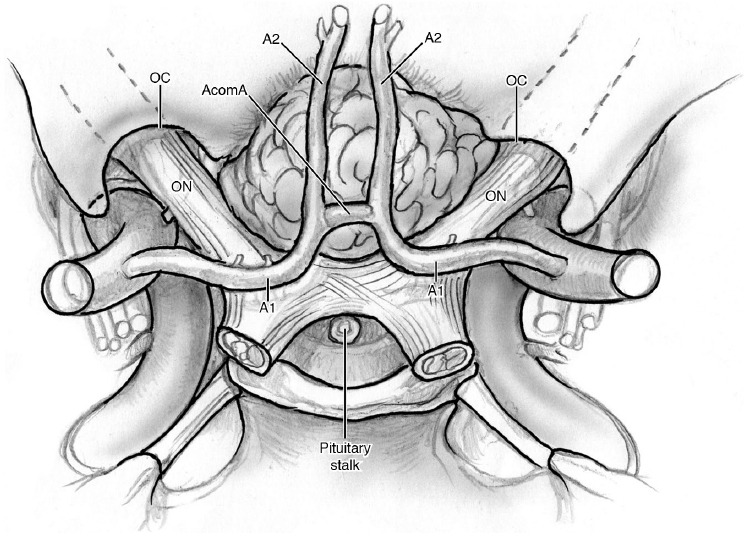

Tuberculum Sellae Meningiomas (Fig. 19.1)

Tuberculum Sellae Meningiomas (Fig. 19.1)

Signs and Symptoms

Signs and Symptoms

Diagnostic Workup

Diagnostic Workup

Treatment

Treatment

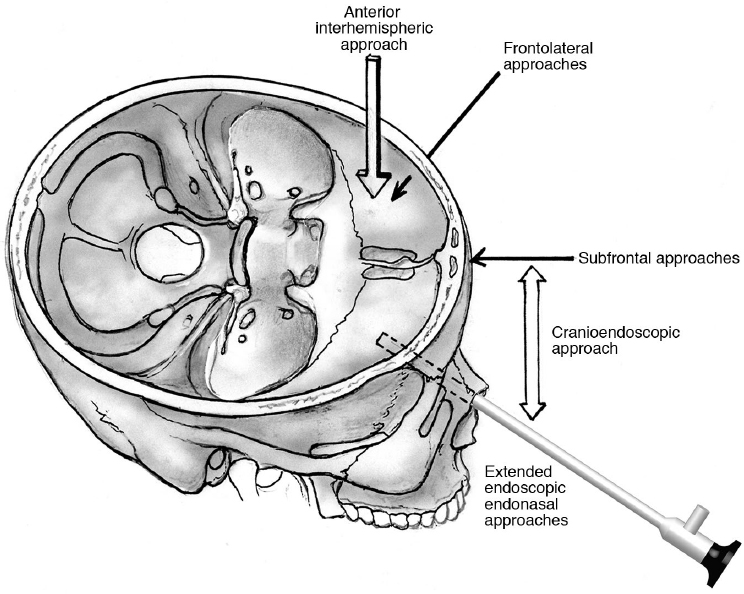

Surgical Approaches

Surgical Approaches

Bifrontal Craniotomy/Subfrontal Approaches

Anterior Interhemispheric Approach

Frontolateral Approaches

Frontotemporal Craniotomy

One-and-a-Half-Fronto-Orbital Approach

Lateral Supraorbital Approach

Supraorbital Approach

Supraorbital Approach

Extended Endoscopic Transnasal Approach

Extended Endoscopic Transnasal Approach

Combined Approaches (Cranioendoscopic Approach)

Combined Approaches (Cranioendoscopic Approach)

Surgical Pearls

Surgical Pearls

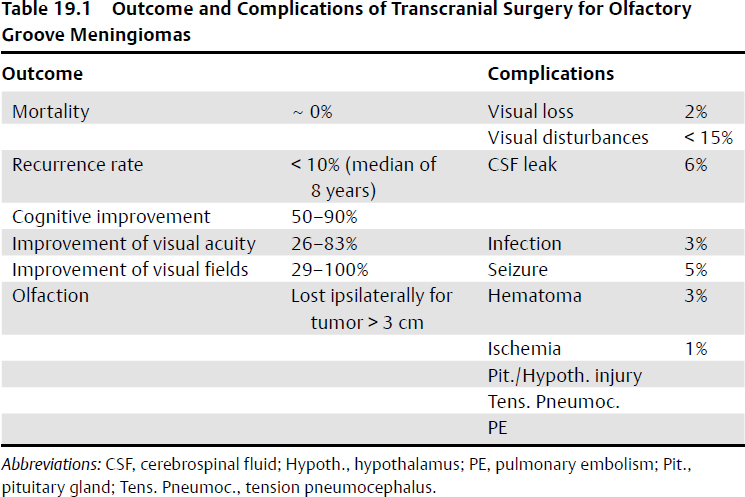

Outcome

Outcome

Neupsy Key

Fastest Neupsy Insight Engine