Approach to the Patient with Acute Headache

David Lee Gordon

Acute headache is a common chief complaint in the emergency department. Primary headache, such as migraine and cluster, is a condition in which headache is a primary manifestation and no underlying disease process is present. Secondary headache is a condition in which headache is a secondary manifestation of an underlying disease process. Most patients with acute headache have primary headache, particularly migraine. Performing an expensive battery of tests on all patients with acute headache is neither cost-effective nor appropriate. Failure to perform diagnostic tests in certain patients with acute headache, however, will result in failure to detect life-threatening, yet treatable, causes. The challenge to the clinician in the emergency setting is not to be lulled to sleep by the frequent migraine attacks and to remain vigilant for the other causes of acute headache.

Migraine is so common that many patients with a secondary headache have a history of migraine, making diagnosis in the acute setting quite difficult. Certain clues in the history and examination should lead to the performance of a diagnostic evaluation in search of the cause of secondary headache. The primary goals of the clinician treating a patient with acute headache are 3-fold: (1) diagnose the cause of headache, (2) provide emergency therapy, and (3) provide the patient with a means of long-term care. These goals apply for patients with primary or secondary headache. Primary headaches are chronic conditions that manifest as multiple acute attacks. Secondary headaches generally are caused by diseases that necessitate both urgent and prolonged care. This chapter deals with the diagnosis of acute headache. The diagnosis of chronic headache and therapy for conditions that cause headache are dealt with elsewhere in Chapter 21.

I. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

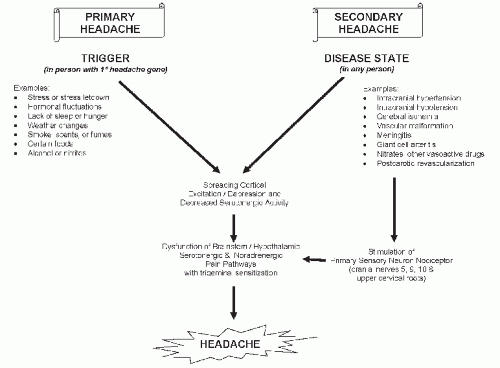

The pathophysiology of head pain is likely the same no matter its cause. Among patients with brain tumor, patients with a past history of primary headache are more likely to have a tumor-related headache than those without a history of primary headache. Thus, the description of head pain alone is not a reliable predictor of whether a headache is primary or secondary. Hemicranial throbbing pain is not always a feature of migraine and can be a feature of intracranial disease. Dull aching head pain occurs in patients with primary headache and patients with brain tumors. Although current understanding of the cause of head pain is not complete, a plausible explanation of the pathophysiologic mechanism of headache that emphasizes the common final pathway of primary and secondary headaches is depicted in Figure 20.1. The schema provides an explanation for the “migrainous” characteristics of some secondary headaches.

II. HISTORY

A. A history of headaches, especially the relation of past headaches to the current headache, is the most important information needed to determine whether a diagnostic evaluation is necessary. A history of similar headaches for many years suggests a primary headache disorder. If, on the other hand, this headache is different in character from past headaches and especially if this is the first headache of the patient’s life, if this is the worst headache that the patient has had, or if the pain is persistent despite the use of measures that relieved previous headaches, a secondary headache is more likely

(Table 20.1). If the patient has had similar headaches for only a few months, weeks, or days, then the possibility of secondary headache increases, and further investigation is warranted. Although it is common for the character of primary headache disorders to change throughout a lifetime, if the current headache differs from previous headaches, the clinician is obligated to investigate.

(Table 20.1). If the patient has had similar headaches for only a few months, weeks, or days, then the possibility of secondary headache increases, and further investigation is warranted. Although it is common for the character of primary headache disorders to change throughout a lifetime, if the current headache differs from previous headaches, the clinician is obligated to investigate.

B. Age at onset of primary headache disorders is generally childhood to young adulthood. An age at onset older than 50 years is particularly suggestive of secondary headache.

C. Activity at onset of headache may suggest cause of headache. Although Valsalva’s maneuver, change in position, or head trauma can precipitate or exacerbate migraine, the presence of any of these features should raise the suspicion of secondary headache.

1. Valsalva’s maneuver may precipitate aneurysmal rupture and resultant subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). It can also precipitate or exacerbate a CSF leak and result in headache due to intracranial hypotension. Headache during coitus can occur as a result of aneurysmal rupture or as a result of coital migraine. The first time a person experiences coital headache, he or she needs a complete evaluation to rule out aneurysmal SAH.

2. Changes in position exacerbate several types of headache. Headaches worse in the supine position suggest increased intracranial pressure (ICP), for example, due to intracranial mass lesion, hydrocephalus, or cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT). Headaches worse when upright (and improved when supine) suggest decreased ICP due to a CSF leak. “Low-CSF-pressure headaches” are especially common after lumbar puncture (LP) but may occur spontaneously or after Valsalva’s maneuver. Mobile intraventricular tumors, such as third-ventricle colloid cyst, may cause intermittent hydrocephalus and headaches that occur only in a particular head position.

3. Head trauma can result in subdural hematoma but may also trigger migraines.

4. Exercise can precipitate migraine or another type of primary headache that is sensitive to indomethacin.

D. The characteristics of a headache are most helpful in determining whether the current headache is different from previous headaches experienced by the patient. Certain characteristics are suggestive of but not pathognomonic for certain causes of headache.

1. Severity of pain is important in that any patient who says he or she has “the worst headache of my life” needs an urgent and complete evaluation, with SAH highest in the differential diagnosis. Both primary headaches and secondary headaches, however, can manifest as very severe or very mild pain.

2. The time frame of onset of pain is more discriminating. Very rapid onset of headache suggests a sudden increase in ICP, particularly due to SAH. Mass lesions such as tumors, abscesses, and subacute or chronic subdural hematoma usually manifest gradually over days to months. Gradual onset of headache over minutes to hours is consistent with migraine. The headache of giant cell (temporal) arteritis tends to be subacute to chronic in presentation.

3. Duration of primary headaches is variable, although they typically last hours to days. Headaches that persist for longer periods despite treatment are worrisome and suggestive of secondary headache.

4. Location of headache and radiation of pain are nonspecific. Many posterior lesions cause frontal headache. Both primary and secondary headaches can be unilateral or bilateral. The pain of both migraine headaches and secondary headaches can radiate.

5. Quality of headache is nondiscriminating. Despite the traditional teaching that migraines must be pounding or throbbing, they are just as often pressure-like, squeezing, sharp, stabbing, or dull. Cluster headaches typically are described as boring, sharp, or lancinating, but so might the headaches associated with other pathologic processes.

6. Associated symptoms of the headache can offer important clues to the cause of headache (Table 20.1).

Nausea and vomiting are common features of migraine, but their presence in a person with new or sudden headache is worrisome because they suggest increased ICP or a posterior fossa lesion.

Photophobia and phonophobia can be part of migraine or a meningeal process such as SAH or meningitis.

Neck stiffness (anteroposterior nuchal rigidity) is typical of a meningeal process.

Change in consciousness rarely occurs in migraine, but its presence should alert the clinician to more serious causes of headache.

Focal neurologic symptoms (e.g., aphasia, visual symptoms, vertigo, ataxia, hemiparesis, or hemisensory deficit) can occur suddenly in association with headache in patients with stroke, seizure, subdural hematoma, and migraine. In this case, migraine is a diagnosis of exclusion, and the clinician is obliged to investigate for underlying disease. Transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) typically last 5 to 20 minutes. Stroke and subdural hematoma symptoms persist. Todd’s paralysis of partial seizures and the aura of migraine often last hours. Focal symptoms of ischemia or hemorrhage typically are “negative” and “static” (e.g., hemibody sensory loss), whereas focal symptoms of migraine typically are “positive” and “migratory” over minutes to hours (e.g., tingling in fingertips progressing to involve the ipsilateral hemibody). Partial seizures can result in symptoms that travel over seconds. Headache in a person older than 50 years with monocular blurred vision and a swollen optic disc suggests the anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (AION) of giant cell arteritis. Binocular visual symptoms can be migrainous or due to occipital pathologic conditions. Certain visual symptoms are classic for migraine, such as scintillating scotomata (blind areas surrounded by sparkling zigzag lines), photopsia (unformed flashes of light), and fortification spectra (slowly enlarging, sparkling, and serrated arcs).

Fever, diaphoresis, chills, or rigors suggest infection. Fever of any cause or generalized infection can cause headache, but if headache, neck stiffness, or decreased consciousness is a prominent symptom, meningitis is highest in the differential diagnosis.

E. Family history of headache is important yet extremely difficult to obtain when a patient has prominent pain, nausea, or cognitive dysfunction as can occur with either primary or secondary headache. Even if the patient is coherent or a relative is available, persons often are not aware of a family history of headache. Migraines tend to be most prominent in early adulthood, when children are too young to realize their parent has headaches, and the patient no longer lives under the same roof with parents or siblings. In addition, rationalization of relatives regarding the cause of headaches (e.g., “sinus” or “tension”) is usually believed by the patient, making a family history of “migraine” difficult to obtain.

FIGURE 20.1 Plausible schema for pathophysiologic mechanism of headache depicts the common final pathway of primary and secondary headaches. |

TABLE 20.1 Clinical Features Suggestive of Secondary Headache | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

III. PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Physical examination may demonstrate signs of a disease that causes secondary headache. A detailed neurologic examination is particularly important; any subtle abnormality should be enough to stimulate a diagnostic evaluation (Table 20.1).

A. General examination.

1. Vital signs. Fever suggests an infectious cause of headache. The presence of arterial hypertension in a patient with headache is common but is rarely causative. Hypertension occurs as a result of migraine attacks, cerebral ischemia, and intracranial hemorrhage.

2. General appearance. Cachexia may be present among patients with chronic diseases such as cancer, AIDS, tuberculosis, and sarcoidosis. Headache due to tumor, abscess, granuloma, or meningitis may be the presenting symptom among such patients.

3. Head. Evidence of cranial trauma includes face and scalp abrasions and contusions and signs of skull fracture—depressed section of skull, Battle’s sign (postauricular ecchymosis), raccoon sign (periorbital ecchymosis), hemotympanum, CSF otorrhea, and CSF rhinorrhea. Skull tenderness to palpation can occur as a result of subdural hematoma. Poor dentition or dental abscesses may result in intracranial abscess. Although tenderness to palpation over the frontal sinus or maxillary sinus may suggest infection of these structures, migraine frequently results in external carotid territory vasodilatation with resultant sinus “fullness,” “pressure,” and tenderness. The presence of fever and purulent discharge from the sinuses is more helpful in diagnosing sinusitis. Tenderness to palpation over the mastoid process suggests mastoiditis, a possible precursor to CVT. Otoscopic examination may show ear infection as well as hemotympanum or otorrhea.

Temporal tenderness or diminished temporal artery pulses in a person older than 50 years are consistent with giant cell arteritis. Auscultation of the skull may demonstrate cranial bruits that occur as a result of arteriovenous malformation (AVM).

Temporal tenderness or diminished temporal artery pulses in a person older than 50 years are consistent with giant cell arteritis. Auscultation of the skull may demonstrate cranial bruits that occur as a result of arteriovenous malformation (AVM).

4. Neck. Meningeal signs include anteroposterior nuchal rigidity, Kernig’s sign (inability to extend the knee after passive hip flexion in the supine position), and Brudzinski’s sign (involuntary hip flexion after passive flexion of the neck in the supine position) and imply the presence of meningitis or SAH. Evidence of neck trauma includes pain on lateral neck movement and neck immobility.

5. Skin. A petechial rash over the axillae, wrists, and ankles is consistent with meningitis due to meningococcus. Skin examination may reveal bruising suggestive of a bleeding diathesis, splinter hemorrhages of distal digits suggestive of cardioembolism, or lesions suggestive of a neurocutaneous disorder such as neurofibromatosis, tuberous sclerosis complex, or cutaneous angiomatosis; these conditions are associated with intracranial lesions that may cause headache. Melanoma suggests the possibility of cerebral metastasis causing headache. Lesions of Kaposi’s sarcoma are consistent with AIDS, which is associated with several intracranial diseases that cause headache.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree