Approach to the Patient with Aphasia

Jeffrey L. Saver

Aphasia is a loss or impairment of language processing caused by brain damage. Language disorders are common manifestations of cerebral injury. Reflecting the centrality of language function in human endeavor, the aphasias are a major source of disability.

I. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

A. Cerebral dominance.

The left hemisphere is dominant for language in approximately 99% of right-handers and 60% of left-handers.

B. Neuroanatomy.

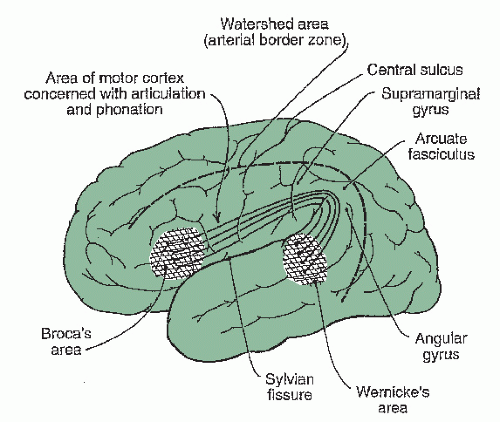

A specialized cortical-subcortical neural system surrounding the Sylvian fissure in the dominant hemisphere subserves language processing (Fig. 3.1). Circumscribed lesions in different components of this neurocognitive network produce distinctive syndromes of language impairment.

II. ETIOLOGY

A. Stroke.

Cerebrovascular disease is a frequent cause of aphasia. The perisylvian language zone is supplied by divisions of the middle cerebral artery, a branch of the internal carotid artery. The classic aphasic syndromes are most distinctly observed in ischemic stroke because vascular occlusions produce discrete, well-delineated brain lesions.

B. Other focal lesions.

Any focal lesion affecting the language cortices will also produce aphasia, including primary and metastatic neoplasms and abscesses. Primary progressive aphasia is a neurodegenerative syndrome characterized by slowly progressive, isolated language impairment in late life and focal atrophy of dominant frontotemporal cortices. Affected individuals frequently develop a generalized dementia after the first 2 years of illness. Among the causes of primary progressive aphasia are (1) frontotempo ral lobar dementia due to tauopathy and (2) a focal variant of Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

C. Diffuse lesions.

Diseases producing widespread neuronal dysfunction will disrupt language processing along with other cognitive and noncognitive neural functions. Traumatic head injury and AD are epidemiologically common causes of aphasic symptoms, although not of isolated aphasia.

III. CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

A. Nonfluency versus fluency.

Fluency refers to the rate, quantity, and ease of speech production. In nonfluent speech, verbal output is meager (<50 words per minute), phrase length shortened (1 to 4 words per phrase), production effortful, articulation often poor, and the melodic contour (prosody) disturbed. Nonfluent speakers often preferentially employ substantive nouns and verbs, eliding small connecting grammatical/functor words (“telegraphic speech”). Conversely, in fluent speech, verbal output is generous (and may even be more abundant than customary), phrase length normal, production easy, articulation usually preserved, and the melodic contour intact.

1. Anatomic correlate.

Nonfluency indicates damage to the frontal language regions anterior to the fissure of Rolando. Fluency signals that these areas are intact.

B. Auditory comprehension impairment.

Impaired ability to understand spoken language ranges from complete mystification by simple one-word utterances to subtle failure to extract the full meanings of complex sentences. In informal conversation, aphasic patients often capitalize on clues from gestures, tone, and setting to supplement their understanding of the propositional content of a speaker’s utterances. Examiners may underestimate the extent of auditory comprehension impairment if they fail to test formally a patient’s comprehension deprived of nonverbal cues.

1. Anatomic correlate.

Comprehension impairment generally reflects damage to the temporoparietal language regions posterior to the fissure of Rolando. Preserved comprehension indicates that these areas are intact. (Comprehension of grammar is an important exception to this rule. Agrammatism is associated with damage to inferior frontal language regions.)

C. Repetition impairment.

Repetition of spoken language is linguistically and ana tomically a distinct language function. In most patients, repetition impairment parallels other deficits in spoken language. Occasionally, however, relatively isolated disordered repetition may be the dominant clinical feature (conduction aphasia). In other patients, repetition may be well-preserved despite severe deficits in spontaneous speech (trans cortical aphasias). Rarely, such patients exhibit echolalia, a powerful, mandatory ten dency to repeat all heard phrases.

1. Anatomic correlate.

Impaired repetition indicates damage within the core perisylvian language zone. Preserved repetition signals that these areas are intact.

D. Paraphasic errors.

Substitutions of incorrect words for intended words are paraphasias. Paraphasic errors are classified into three types.

1. A literal or phonemic paraphasia

occurs when only a part of the word is misspoken, as when “apple” becomes “tapple” or “apfle.”

2. A verbal or global paraphasia

occurs when an entire incorrect word is substituted for the intended word, as when “apple” becomes “orange” or “bicycle.” A semantic paraphasia arises when the substituted word is from the same semantic field as the

target word (“orange” for “apple”). Fluent output contaminated by many verbal paraphasias is jargon speech.

target word (“orange” for “apple”). Fluent output contaminated by many verbal paraphasias is jargon speech.

3. A neologistic paraphasia

occurs when an entirely novel word not extant in the speaker’s native lexicon is substituted for the intended word, as when “apple” becomes “brifun.”

4. Anatomic correlate.

Paraphasic errors may occur with lesions anywhere within the language system and do not carry strong anatomic implications. To some extent, phonemic paraphasias are more common with lesions in the frontal language fields and global paraphasias more common with lesions in temporoparietal areas.

E. Word-finding difficulty (anomia).

Retrieval of target words from the lexicon is vir tually always disturbed in aphasia. Patients may exhibit frequent hesitations in their spontaneous speech while they struggle with word-finding. Circumlocutions transpire when patients “talk around” words they fail to retrieve, providing lengthy definitions or descriptions to convey the meanings of words they are unable to access.

1. Anatomic correlate.

Word-finding difficulty occurs with lesions located throughout the language-dominant hemisphere and possesses little localizing value.

F. Reading and writing.

In most cases of aphasia, reading impairment (alexia) and writing impairment (agraphia) parallel oral language comprehension and production deficits. Occasionally, however, isolated reading impairment, writing impairment, or both can occur in the setting of fully preserved oral language function.

1. Anatomic correlate.

The anatomy of reading and writing incorporates both the core perisylvian language zones and additional function-specific sites. Reading requires primary and higher-level visual processing in the occipital and inferior parietal lobes. Writing depends on visual stores in the inferior parietal lobe and graphomotor output regions in the frontal lobe.

IV. EVALUATION

A. History.

Abrupt onset of language difficulty suggests a cerebrovascular lesion. Subacute onset may suggest tumor, abscess, or other more moderately progressive process. Slow onset suggests a degenerative disease, such as AD or frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Interviewing family members and other observers is crucial when the patient’s language difficulty limits direct history-taking.

B. Physical examination.

1. Elementary neurologic signs.

A detailed elementary neurologic examination allows identification of motor, sensory, or visual deficits that accompany the language disorder, aiding neuroanatomic localization. Important “neighborhood” signs are the presence or absence of hemiparesis, homonymous hemianopia or quadrantanopia, and apraxia.

2. Mental status exam.

It is important to assess the patient’s wakefulness and attentional function, lest language errors resulting from inattentiveness be wrongly ascribed to intrinsic linguistic dysfunction. Nonverbal tests to evaluate memory, visuospatial, and executive functions should be utilized if severe language disturbance precludes routine verbal assessment.

3. Language exam.

A careful language exam is critical in the evaluation of aphasia, profiling the patient’s impaired and preserved language abilities and allowing a syndromic, localizing diagnosis.

Spontaneous speech. The patient’s spontaneous verbal output, in the course of conversation and in response to general questions, should be judged for fluency ver sus nonfluency and presence or absence of paraphasias. It is important to ask open-ended questions such as “Why are you in the hospital?” or “What do you do during a typical day at home?” because patients may mask major language derangements with yes-no answers and other brief replies to more structured interrogatories.

Repetition. The patient is asked to repeat complex sentences. If difficulty is evidenced, simpler verbal sequences from single-syllable words to multisyllabic words and short phrases are given to determine the level of impairment. At least one sentence rich in grammatical/functor words, such as “No ifs, ands, or buts,” should be employed to test for isolated or more pronounced difficulty in grammatical repetition, as may be seen in Broca’s and other anterior aphasias.

Comprehension. An initial judgment of auditory comprehension can be made in the course of obtaining the medical history and from spontaneous conversation. Tests that require no or minimal verbal responses are essential to the evaluation of auditory comprehension in individuals with severe disturbance of speech production and intubated patients.

Commands. One simple bedside test is verbally to instruct the patient to carry out one-step and multistep commands, such as “Pick up a piece of paper, fold it in half, and place it on the table.” Cautions to recall when interpreting results are (1) apraxia and other motor deficits may cause impairment not related to comprehension deficit and (2) midline motor acts on command, such as closing/ opening eyes and standing up, draw on distinct anatomic systems and may be preserved even in the setting of severe aphasic comprehension disturbance.

Yes/no responses. If the patient can reliably produce verbal or gestural yes/no responses, this output system may be used to assess auditory comprehension. Questions of graded difficulty should be employed for precise gauging of the degree of comprehension disturbance, using queries ranging from simple (“Is your name Smith?”) to complex (“Do helicopters eat their young?”).

Pointing. This simple motor response also permits precise mapping of comprehension impairment by means of questions of graded difficulty. The examiner should employ both simple pointing commands (“Point to the chair, nose, door”) and more lexically and syntactically complex pointing commands (“Point to the source of illumination in this room”).

Naming. Difficulty with naming is almost invariable in all the aphasia syndromes. Consequently, naming tasks are sensitive, although not specific, means of testing for the presence or absence of aphasia.

Confrontation naming. The patient is asked to name objects, parts of objects, body parts, and colors pointed out by the examiner. Common, high-frequency words (“tie,” “watch”) and uncommon, low-frequency words (“knot” of the tie, “watchband”) should be tested.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree