Approach to the Patient with Sleep Disorders

Mark Eric Dyken

This chapter focuses on primary sleep disorders described in the second edition of the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD). The greatest difficulties in approaching patients with sleep disorders often relates to an incomplete sleep history, as only a few diagnoses require formal polysomnography (PSG). Nevertheless, the patient usually cannot recall a pathologic event that occurs during sleep, and as such, an attempt to substantiate the sleep history with a bed partner, family member, or close associate should be made.

I. GENERAL APPROACH

A. The sleep history.

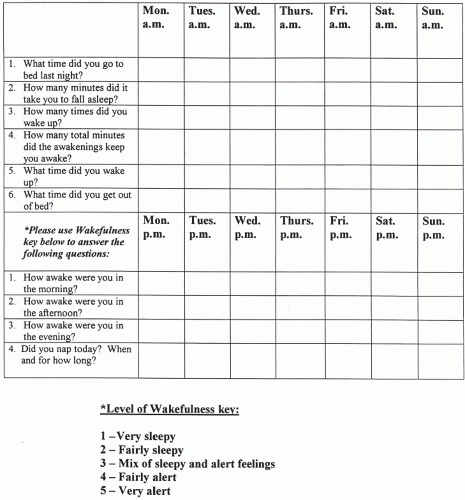

What is the sleeping environment and bedtime routine? When is bedtime (regular or irregular)? What is the sleep latency (the time to fall asleep “after the head hits the pillow”)? What is the sleep quality? Is it restful or restless and, if restless, why? How many arousals occur per night and for what reasons? What is the final awakening time? Is assistance in waking necessary? How does the patient feel on waking? How many hours of sleep are needed for refreshment? Does the patient nap, and, if so, how often, how long, and how does the person feel after the nap (refreshed, unchanged, and worse)? Does the patient experience excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) or frank sleep attacks? A 2-week sleep diary, started prior to the initial clinic appointment, can diagnose disorders like inadequate sleep hygiene; a problem in 1% to 2% of adolescents and young adults, and in up to 10% of the sleep-clinic population that presents with insomnia (Fig. 9.1).

1. The degree of sleepiness can rate the severity of any sleep disorder through operational definitions: mild—sleepiness that impairs social or occupational performance during activities that require little attention (reading or watching television); moderate— sleepiness that impairs performance during activities that require some attention (meetings and concerts); and severe—sleepiness that impairs performance during activities that require active attention (conversing or driving).

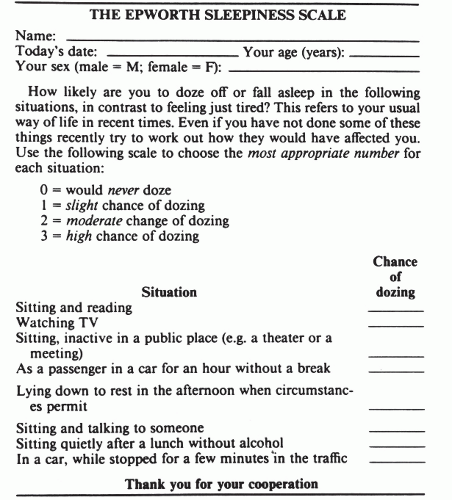

2. Subjective measure scales, such as the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, can be used to qualify, quantify, and follow problems with sleepiness (Fig. 9.2). Chronically sleepdeprived persons can underestimate their sleepiness. Over time they lose the reference point from which to make comparisons and forget what it feels like to be fully rested. In such cases, excessive sleepiness can be reported as memory loss, slow mentation, and amnestic periods with automatic behavior.

B. The wake history.

A history of insomnia and EDS can lead to, exacerbate, or result from a variety of medical and mental disorders, and from drug or substance use/abuse.

II. TYPES OF SLEEP DISORDERS

A. Insomnia.

The ICSD criteria demand a history of difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep, or of waking up too early, or sleep that is chronically nonrestorative or poor in quality, and that the problem occurs despite adequate opportunity and circumstances for sleep. It also requires subsequent daytime impairment evidenced by at least one of the following: sleepiness, fatigue, malaise, impaired attention, concentration, or memory, social, vocational, or school dysfunction, tension, mood disturbance, reduced motivation, energy, or initiative reduction, errors or accidents at work or driving, headache, or gastrointestinal symptoms.

1. Adjustment (acute) insomnia. This occurs in response to a clearly identifiable stressor and is expected to resolve when the stress ends or the patient adapts. Adjustment insomnia is often associated with anxiety and depression related to the specific stressor. The 1-year prevalence in adults is 15% to 20%, it is more common in women and older adults, and it may predispose to maladaptive behaviors and more persistent forms of insomnia.

2. Psychophysiological insomnia.

This is a conditioned insomnia due to learned, sleeppreventing associations. It can represent persistent adjustment insomnia, where an external (or internal) stressor leads to a state of arousal “racing mind” in association with bedtime at home (patients often sleep better in the sleep lab; the “reverse first-night effect”). This affects 1 % to 2 % of the general population, is more frequent in women and adolescents, and is rare in children.

3. Paradoxical insomnia.

Patients complain of severe insomnia with no objective evidence of disturbed sleep or daytime impairment. PSG studies show that these individuals overestimate their sleep latencies and underestimate their sleep times. Patient concerns are not alleviated when they are presented with these objective findings. Highfrequency activity on EEG power-density measures may alter sleep perception in this

patient population. Paradoxical insomnia occurs in <5% of insomniacs, is more common in women and young to middle-aged adults, and may be associated with neuroticism and depressive traits.

patient population. Paradoxical insomnia occurs in <5% of insomniacs, is more common in women and young to middle-aged adults, and may be associated with neuroticism and depressive traits.

4. Idiopathic insomnia.

This lifelong disorder is reported in 1% of young adults, begins in infancy or early childhood. It has no known precipitators or major psychological concomitants, but may be associated with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and dyslexia. A genetic abnormality in sleep/wake mechanisms is suspected. PSG often shows reduced body movements despite severely disturbed sleep.

5. Insomnia due to mental disorder, not due to substance or known physiological condition.

In this diagnosis, insomnia is a symptom of a mental disorder, but its severity demands treatment as a distinct problem, which often improves the underlying mental disorder. Major depression is frequently associated with insomnia and reduced rapid eye movement (REM) sleep latency, but PSG is not needed for diagnosis.

6. Inadequate sleep hygiene.

This presents as a primary or secondary diagnosis in over 30% of sleep-clinic patients. It involves two categories of habits inconsistent with good sleep: practices that produce increased arousal (e.g., caffeine and nicotine use) and practices that are inconsistent with the principles of sleep organization (variable bedtime and awakening times). Important factors can include engaging in mentally or physically stimulating activities too close to bedtime and failure to maintain a comfortable sleeping environment.

7. Behavioral insomnia of childhood.

There are 2 types seen in up to 30% of children (possibly more frequent in boys) after 6 months of age. Sleep-onset association type occurs with dependency on a specific stimulation, object, or setting for sleep. Sleeponset associations are extremely prevalent and are only a disorder if highly problematic. Limit-setting type occurs with bedtime stalling, or refusal in toddlers and preschoolers. This problem is often due to poor practices of the caregiver.

8. Insomnia due to drug or substance.

This is suppression or disruption of sleep during consumption; or exposure to a drug, food, or toxin; or upon its discontinuation. This affects 0.2% of the general population and 3.5% of those presenting to formal sleepclinics. The PSG in chronic alcohol withdrawal can reveal light and fragmented sleep that may persist for years.

9. Insomnia due to medical condition and physiological (organic) insomnia.

Disorders that cause discomfort (comfort is necessary for normal sleep) and neurodegenerative problems (with disruption of normal central sleep/wake mechanisms; poorly formed or absent sleep spindles are common) are representative of many possible etiologies. This diagnosis should only be considered when insomnia causes marked distress and warrants specific attention.

B. Sleep-related breathing disorders (SRBDs).

In addition to the wake/sleep history, PSG is required in diagnosing SRBDs. PSG is the combined sleep monitoring of EEG, electromyography (EMG), electrooculography (EOG), and physiologic measures that include airflow, respiratory effort, and oxygen saturation (SaO2). PSG differentiates four sleep stages—non-REM (NREM) stages N1, N2, and N3, and REM (stage R). An obstructive apnea is a drop in airflow by >90%, in association with continued inspiratory effort, for >10 seconds in adults, or the duration of 2 baseline breaths in children. A central apnea is an absence of inspiratory effort for >10 seconds in adults, or, in children, for 20 seconds, or the duration of 2 baseline breaths in association with an arousal, awakening, or a >3% SaO2 reduction. A mixed apnea occurs when there is initially absent inspiratory effort, followed by resumption of inspiratory effort in the second part of the event. Hypopneas in adults occur with a >10 second period of reduced airflow of >30% or >50%, with respective SaO2 reductions of >4% or >3% (or an associated arousal). In children, a hypopnea requires a >50% fall in airflow for a duration of 2 baseline breaths, in association with an arousal, awakening, or >3% SaO2 reduction. Severity of a SRBD is suggested by the apnea-hypopnea index ([AHI]; the average number of apneas and hypopneas per hour of sleep). In adults, an AHI of 5 to 15 is considered mild; 15 to 30, moderate; and >30, severe.

1. Central sleep apnea (CSA) syndromes.

Primary CSA.This idiopathic disorder is more frequent in middle aged to elderly males, associated with low normal waking PaCO2 (<40 mm Hg), and high chemoresponsiveness (evidenced as central apneas) to the normal rise in PaCO2 that occurs in sleep. It is significant when there are complaints of EDS, insomnia, or arousals with shortness of breath, and the PSG shows an AHI > 5.

Cheyne-Stokes’ breathing pattern (CSBP). PSG defines CSBP as at least 3 consecutive cycles of a cyclic crescendo and decrescendo change in breathing amplitude, with a central AHI of >5 and/or a cyclic crescendo and decrescendo change of >10 consecutive minutes. CSBP is most prominent in NREM sleep (usually absent or attenuated in REM). It occurs predominately in men >60 years of age, with a prevalence up to 45% in the congestive heart failure (CHF) population, and in 10% of strokes. CHF (a poor prognostic sign), stroke, and possibly renal failure are the most important precipitating factors.

High-altitude periodic breathing. This is an acute response to a relatively rapid ascent to altitudes >4,000 m, where (usually the first night) there are recurrent central apneas in NREM sleep that alternate with hyperpneas in cycles of 12 to 34 seconds (often leading to frequent arousals with shortness of breath and EDS). This is considered a normal, and transient, adaptive phase to higher altitudes.

CSA due to medical condition (not Cheyne-Stokes) and due to drug or substance. A majority of the medical conditions with CSA are associated with brainstem lesions, cardiac, or renal disorders. Regular use (>2 months) of long-acting opioids (methadone, time-release morphine, and hydrocodone), can lead to CSA (often in

association with obstruction, hypoventilation, and periodic breathing). The presumed etiology is from an effect on //-receptors on the ventral surface of the medulla.

Primary sleep apnea of infancy (apnea of prematurity <37 weeks conceptual age, apnea of infancy >37 weeks, <1 year conceptual age). Central, mixed, obstructive apneas or hypopneas (most notably in active/REM sleep) associate with signs of physiologic compromise (hypoxemia, bradycardia, the need for resuscitative measures), but progressively decrease as the patient matures during the early weeks of life. The prevalence varies inversely with conceptual age (in 84% of infants <1,000 g, and <0.5% of full-term newborns), as it is related to developmental immaturity of brainstem respiratory centers. This has not been established as an independent risk factor for sudden infant death syndrome.

2. Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) syndromes.

OSA is associated with repeated episodes of upper airway obstruction. From 30 to 60 years of age, the prevalence ranges from 9% to 24% for men and 4% to 9% for women. Obstructions often result in oxygen desaturation, elevation in PaCO2, and arousals, which disrupt sleep continuity and can lead to EDS. This syndrome often occurs among sleepy, middle-aged, overweight men with insomnia who snore. Premenopausal women are less commonly affected. This disorder also has been associated with systemic and pulmonary hypertension, nocturnal cardiac arrhythmia and angina, gastroesophageal reflux, nocturia, and an overall reduction in quality of life. Predisposing factors include familial tendencies, redundant pharyngeal tissue (e.g., adenotonsillar hypertrophy), craniofacial disorders (e.g., micrognathia, retrognathia, and nasal obstruction), endocrinopathy (e.g., acromegaly and hypothyroidism with myxedema), and neurologic disease.

OSA, adult.

History. The patient or bed partner often reports restless, unrefreshing sleep and sleep maintenance insomnia with arousals associated with gasping, choking, or heroic snoring, possibly exacerbated by fatigue, alcohol, weight gain, or the supine sleeping position. Snoring may force the person to sleep alone and persist even when sitting. Although patients may not report daytime sleepiness, problems with fatigue, memory, and concentration are frequent. A family history of similar problems should be carefully sought.

Examination. The blood pressure, body mass index (BMI = weight in kilograms per square meter of height) and neck and waist circumference should be documented, as hypertension and obesity may relate to OSA. Of general concern (following western standards) are a BMI >30 kg per m2, a neck circumference of >40 cm, and a waist circumference (often measured at the iliac crest) >102 cm in men, and >88 cm in women. These are frequent signs in OSA that may predict comorbidities in the metabolic syndrome, heart disease, and stroke. Oral and nasopharyngeal patency and abnormalities of the tonsils, adenoids, tongue, soft and hard palate, uvula, nasal septum, turbinates, and temporomandibular joint as well as fatty infiltration of soft tissues in the upper airways should be documented.

PSG. Recurrent obstructions often result in microarousals/arousals, which contribute to EDS (however, the frequency of events correlates poorly with sleepiness severity). Events generally appear worse in the supine position and during REM sleep. Tachy-brady cardiac arrhythmias and asystole may be documented. The diagnosis of OSA is considered with an AHI >5, when there is at least one symptom that may include EDS, insomnia, arousals with shortness of breath or choking, and witnessed loud snoring or apneas. The diagnosis can also be given with an AHI >15 in the absence of symptoms.

Differential diagnosis. Loud snoring and respiratory effort related arousals (RERA), as part of the upper airway resistance syndrome (UARS), can lead to EDS with no PSG evidence of OSA (as RERA are pathophysiologically similar to obstructions). During PSG, defining RERA requires esophageal balloon (or nasal pressure/inductance plethysmography) monitoring that reveals >10 second episodes of, respectively, increasing negative pressure, or flattening of nasal pressure waveforms (that correspond to increased respiratory effort), which terminate with arousal.

Other tests. In severe cases, an interdisciplinary approach may necessitate ECG, chest radiography, echocardiography, and pulmonary function tests (addressing pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular hypertrophy), cephalometric evaluations of the upper airways, and extensive cerebrovascular assessments.

OSA, pediatric. The prevalence of OSA is 2% in the general pediatric population, with girls and boys being affected equally, but with a higher prevalence in African American relative to Caucasian children. Some children may have OSA breathing patterns similar to adults, nevertheless, younger children may be prone to obstructive hypoventilation (long periods of persistent partial upper airway obstruction).

History. Snoring and difficulty breathing are common; often with reports of associated neck hyperextension and diaphoresis. Cognitive and behavioral complications (ADHD) are frequent, with EDS being reported especially in older children.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree